Articles and features

Still Life: This Classic Painting Genre Continues To Endure

By Lauren Gee

” Still life is the touchstone of painting “

Édouard Manet

With the earliest known examples existing amongst frescoes uncovered at Pompeii, the still life has been a staple of artistic production for centuries. Derived from the Flemish ‘stillleven’ during the Dutch Golden Age of the mid Seventeenth century the genre was practised at that time to show the surge in cultural and economic prominence of the burgeoning mercantile nation. Still life painting flowered as a means to show the achievements, but also transience, of ordinary human life. The genre also enabled artists to demonstrate their virtuosity in the depiction of finely crafted goods, which were increasingly emblematic of the emergent middle class’ lifestyle. The still life, also called ‘nature morte’ in French has also been used as a vanitas device – a means to show the fleeting temporality of human existence and as a reflection on the vices and virtues of life. It was represented as a class of painting unto itself in the various official salon exhibitions of Europe during the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, but despite the breakdown of the official art system and the emergence of the avant grade in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries the still life shows no sign of going away.

Henri Fantin-Latour

Known for his quietly rendered still lifes, French painter Henri Fantin-Latour was an artist whose work evolved during the advent of Impressionism. He might have been a traditionalist in his approach, but was a master at depicting serene corners of domestic life with soft and subtle brushwork. The assymmetrical table position and composition is framed with the insouciance of quick photographic snap, an emergent medium well known to the artist. Teeming out of the vase in different directions, as though looking for the light, the delicacy of the flowers’ curled petals recall the pastel flora of the Eighteenth century rococo, but reimagined as a painting for the modern life of the day. Balance and poise was always integral to Latour’s work; the scattering of clementine segments in the foreground of the painting draw the viewer in, our eyes gently steered by the artist by the play of light and shadow on the various subjects. The porcelain pot affirms a sense of domesticity, a prevalent theme in the cult of still life painting and rooted in the sanctuary of the home life.

Paul Cézanne

“with an apple I will astonish Paris”

Paul Cézanne

The melancholy of the memento mori is embraced here by French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne. Vanitas, Latin for Vanity, was a work intended to remind the viewer of their mortality, the futility of pleasure and the imminence of death. The vanitas image has had a longstanding synergy with the still life, where objects are carefully rendered by the artist to symbolise the fleeting nature of human life. Cézanne’s bold brush shows a further loosening of the Impressionist style, and has long been considered a precursor to the jarring modernism of Cubism a decade later. The darkness of the background is foreboding and threatening to the vibrant green and red hues of the pears, the skull faces towards the collection of pears, producing a contrast between their sense of life and its own hollow structure. Death seeps out of the skull claiming the pear closest as its first victim, decaying or half eaten, leaving a misshapen form in its wake. Life is never far from death.

Giorgio Morandi

Italian painter Morandi treats his still life works as portraits, his chosen domestic objects reimagined as a composition of figural elements, a gathering. Most of his still lives use his famed muted and earth-toned palette, giving his objects and composition a feel of warmth and humility. The painted objects, often jugs and assorted pots, sit in conversational clusters, tangibly human in their interactions and in their separation across the canvas surface. In this example, the compositional tension created by these demarcations is strengthened by the jug, which turns away from the first row of objects, complicating the sense of harmony one expects from a still life. Morandi is clever in concealing these conflicts within a seemingly simplistic composition. These powerful subtleties have led Morandi to be regarded as one of the most renowned painters of the twentieth century, and an artist almost entirely associated with the still life genre, embracing it, evolving it and making it his own.

Jasper Johns

In the mid twentieth century still life is invigorated by American artist Jasper Johns with an attitude that foreshadows the emergence of Pop Art. Though Johns is known primarily for his painting, this sculptural take on the still life is stoic in its simplicity. Moving away from the painterly conventions more readily associated with the still life, the identity this work in its conformity to the genre is clearly perceptible in its honest portrayal of the household object. Johns is well known for his focus on American Culture, both predating and overlapping the Pop Art movement of the 60s, the most famous examples perhaps being his versions of the American flag. This sculpture pays homage to the cult item, in the same way the traditional still life does, but also the branded item, a feature of Pop. The still life is a medium with great anthropological insight, what is on one’s kitchen table produces a telling account of those who would be sat around it. Johns is slightly humorous in this sense, a meagre offering of two beers, a humorous portrait – Johns modernises a genre that still has great contemporary relevance.

Wayne Thiebaud

We are at a 1970’s dinner party, the food is cold, but no one cares because it is gaudy, kitsch and ridiculously styled. This is the world that Wayne Thiebaud has thrown us into with his energetic and cheerful still life, a portrait of the seventies. Aperitifs take the form of synchronized swimming events, the symmetry and vibrancy of which animate the painting’s busy composition. In contrast to the classic origins of the still life which framed its select objects, Thiebaud’s composition extends beyond the pictorial frame, informing us that this is a cropped view of an extended table of food. The shadows that cast bluish pools across the white table cloth, inspire a sense of anticipation, as though the guests’ arrival is imminent. This snapshot of time, a moment of expectation encapsulates the role of the still life, to not only portray a moment but imbue it with a quiet sense of importance. There is a truthfulness to Thiebaud’s work that heralds the inventive flamboyancy of the home cook and the wholesome excess of the home of the era. Thiebaud uses the still life as a pop art vehicle for his narrative about modern life, consolidating its contemporary relevance.

Marc Quinn

Made from ten pints of the artist’s blood, Marc Quinn’s Self confronts the incremental ageing process and its precarious road to death. Quinn’s work then situates itself amongst the great vanitas works of art history. The sculpture references a period of alcoholism in the artist’s life and the consuming dependency that came with it. Requiring constant electricity to retain the right temperature or else it will melt, Quinn’s head directly mimmicks his reliance on alcohol. The head, though detached from the body, transforms the gallery space into a mortuary and in doing so encourages the dark and silent reflection of a vanitas painting. Stripped of the anecdotal accompanying fruit or tableware, Quinn portrays the core and inescapable presence of death with a stark directness. There is a stillness to the work that feels peaceful and calm rather than upsetting and gory. Quinn’s head is a contemporary ode to the genre – conceptual, serene and shocking in equal measure. Like the traditional still life painters who used to make several versions of the same scene, Quinn makes a head every five years, capturing the process of ageing honestly in his use of materials and process.

Josiah McIlheny

31 1/4 x 188 x 18 3/4 inches

American sculptor Josiah McIlheny brings new depth to the still life, with the infinite meandering of reflections produced in his mirrored cabinets. His hand blown objects sit proudly in regimented rows, each forming and consumed by unending factory lines disappearing into infinity. Mclheny is well known for his glass blowing, a practice whose rarity imbues each of his objects with a sense of preciousness. The mirrored surface of each of the vials is ostentatious in their gleaming perfection. They sit as an untouched bounty of silver to be used for a best occasion which never arises, playing to the relatability and domesticity of the still life we are familiar with. Though sculptural, there is something digital, mechanised or other-worldly in the futuristic appeal of the work. Mclheny then reveals a shift in what is valued. Elaborate displays of wealth once consisting of lobsters and ornate carafes of wine now show technology and futuristic ambition. This is the contemporary still life for the digital age.

Ori Gersht

The traditional still life was intended to capture a moment in time unnoticed or dismissed in its commonality, Gersht turns this on its head by using the camera to capture moments so dynamic and explosive, they are but a blur to the naked eye. Using an air rifle, Gersht shoots his photographic subjects, catching the moment they shatter into tiny pieces. Gersht’s use of flowers hark back to the classic still life and also to the endangered flowers of his home country Israel, a material for him to explore ideological and mythological narratives that centre around the idea of homeland. Gersht uses the traditional passivity and stasis of the still life as a style from which to grow political and reflective thought. In using art history to power his contemporary ideas of what a still life is and can be, Gersht pays homage to the greats that produced such a revered style, bringing their works into the twenty first century with startling effect.

Mat Collishaw

Mat Collishaw’s bleak but intimate take on the still life, pays tribute to the genre of vanitas with a dark humour. Capturing the chosen last meal of death-row inmates before their execution, Collishaw takes advantage of the capacity of the still life to render an absent subject somehow present, forming a portrait via the story the accoutrements tell. In their gentle honesty there is something almost intrusive about the works, an almost portrait of an individual so painfully and knowingly close to the end of their lives. The pastiche of traditional Flemish or Spanish Old Master examples is at first glance amusing, yet refection on the pitiful circumstances causes a sense of reflective guilt to fill the spectator. Of the three aspects which comprise a vanitas, the futility of pleasure stands out most glaringly; the meaninglessness of being able to choose one’s last meal against the symbolic gesture it represents; a conflict which Collishaw does little to settle in his ghostly series. The inmates’ whole lives are reduced to this last banal indignity – the hopeless pathos present in these still lives is inescapable and haunting.

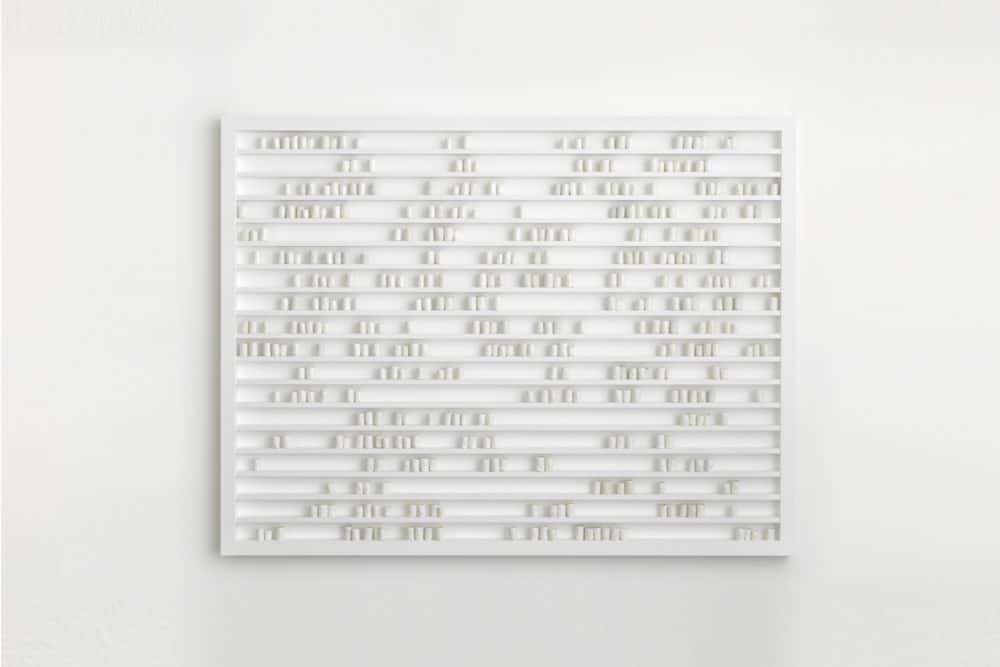

Edmund de Waal

Edmund de Waal’s art is populated by his iconic porcelain vessels, the delicacy of which consecrate his title as master potter. His works recall Mondrian plus many other exemplars of the modernist grid, but also pay simultaneous homage to the still life of the humble object. The clean, subdued colour palette also recalls Morandi. De Waal’s artistic sensibility imbues his vessels with an illusory weightlessness, delicate in their assured and soothing presence. The cool whites and muted tones of the porcelain pots place as much significance on the space in between each object as they do the hand crafted objects themselves. This focus on absence recalls Rachel Whiteread whose work draws attention to unclaimed space through large and extraordinary casts. De Waal’s breathturn works to the same effect. The spaces act as pauses, rendering his shelves of pots as analogous to a punctuated page of text. De Waal transforms the still life and the familiar objects it uses into a large linear composition heralding artistic influences from the gamut of modernism, with particular nods to minimalism.

Relevant sources to learn more

10 best contemporary still lifes

MoMA on still life