Articles and Features

The Other Joseph Beuys: The Drawings of the Myth-Making Action Artist

By Shira Wolfe

“I am interested in transformation, change, revolution.”

Joseph Beuys

This article series explores the lesser-known artistic output of artists who became known for another medium or genre of art. Often, great artists wear many different hats, but break through and achieve acclaim because of their work in one specific medium. We aim to highlight the multifaceted nature of their talent by shining a light not on what they are best known for, but on the lesser-known side of their artistic production. Last week’s edition featured the visual art of the legendary punk-poet Patti Smith.

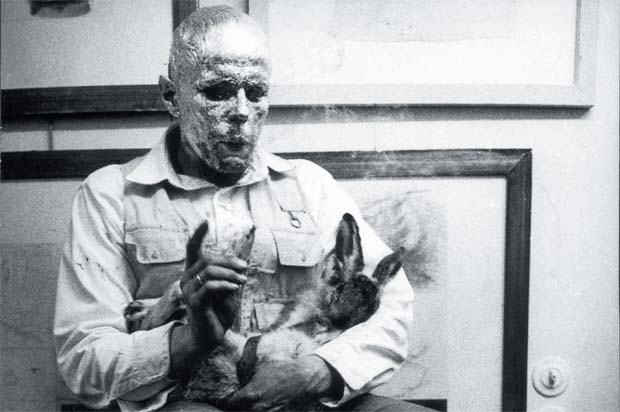

This week, we explore the drawings of Joseph Beuys, the German artist briefly associated with Fluxus who famously proclaimed that “everyone is an artist,” and was known for making his own life his masterwork, as well as for his iconic performative “actions,” such as I Like America and America Likes Me (1974) and How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965). The drawings of Beuys remain lesser-known works, which nonetheless can be seen as the drafts for his all-encompassing life masterwork and are important pieces in the puzzle comprising Beuys’s full artistic genius.

Joseph Beuys – Life Course/Work Course and the Myth of the Artist

Understanding the art of Joseph Beuys involves understanding the artist’s dedication to living a life not merely as an artist, but living a life completely in and as art. Beuys introduced his life in a narrative text entitled Lebenslauf/Werklauf (Life Course/Work Course), first published in 1964. The text can be interpreted as laying the foundations for his most important “series,” namely the events of his life as an artist.

Everything in the text functions together as the artist’s signature, just as his many activities do. The first entry, for example, denotes his birth in 1921 as “Kleve Exhibition of a wound drawn together with plaster.” By using the word “exhibition,” Beuys employs a strategy conflating the rituals of art and life. The date of birth of the artist here becomes an actual artistic presentation of the birth of a human being. Moreover, the choice of the wound as a metaphor is important here.

The image of the wound is central to Beuys’s work and illuminates the historical context within which Beuys operated. Beuys’s myth-making addresses a powerfully charged moment in history, namely the post-war years in West Germany when the population experienced a collective identity crisis while carrying the legacy of Nazism and World War II. Though Beuys did not share many details about his military service during WWII, when he served in the Luftwaffe, his work was very much a product of his past, and the past and present of his country.

Beuys saw West Germany’s focus on material recovery rather than spiritual recovery as a grave problem. As such, his work takes its place within a vanguard of postwar artists and intellectuals who dared to investigate issues largely left unspoken in everyday discourse. The most famous anecdote from the war period, which came to serve as one of the best-known myths surrounding Joseph Beuys, is the story that Beuys was shot down in the Crimea in 1943 and saved by a group of Tatar nomads who used animal fat and felt as salve for his wounds and insulation from the cold. Beuys often explained that this is where his preferred use of animal fat and felt came from. It is clear that Beuys’s presentation of the wound in his art, with his body, his objects, and his discourse, provided a vehicle for a healing process in society. Engaging Germany’s Nazi past, Beuys framed his work as a type of homeopathic therapy: “the Art Pill.”

Joseph Beuys’s Drawings

The drawings of Joseph Beuys, though always in the background, overshadowed by his performance work, form a continuous line through his other works. They form an inextricable part of Beuys’ life Gesamtkunstwerk, which combined teaching with performance, sculpture and political activism. A clear example of this is one of the best-known images of Beuys, seated in an art gallery, cradling a dead hare in his arms, his head coated with honey and gold leaf. A group of large drawings hangs on the wall behind him, and the drawings in question are his own. This action was called How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare.

It is generally assumed that there are over 10,000 drawings by Joseph Beuys. He was constantly drawing: when he was travelling, when he was watching TV, or in the midst of a private conversation, even in performance. This prolific attitude towards drawings implies that, for Beuys, it was as essential an activity to life as any other. Drawing had been his major output throughout the 1950s. By the 1960s, drawing had become a vital component of his performance and activism which would characterise his further career. Beuys consistently referred to his early drawings as the source of all his ideas, as catalysts for his work across all other media. The importance attributed by Beuys to his drawings emphasises the autobiographical voice in his work as a whole, placing idea rather than physical product at the forefront.

Some of Beuys’s drawings employ unconventional mediums such as hare’s blood or margarine or use the backs of envelopes or commercial stationery. Some incorporate photographs, pressed flowers, and other organic materials, emphasising how they functioned as a reservoir of ideas for Beuys’s sculpture, actions and other projects.

“No artist of his generation so powerfully projected that disposition of his time, legitimised by Duchamp, for the artist’s life to be his master-work.”

Richard Hamilton

Joseph Beuys’s Figures

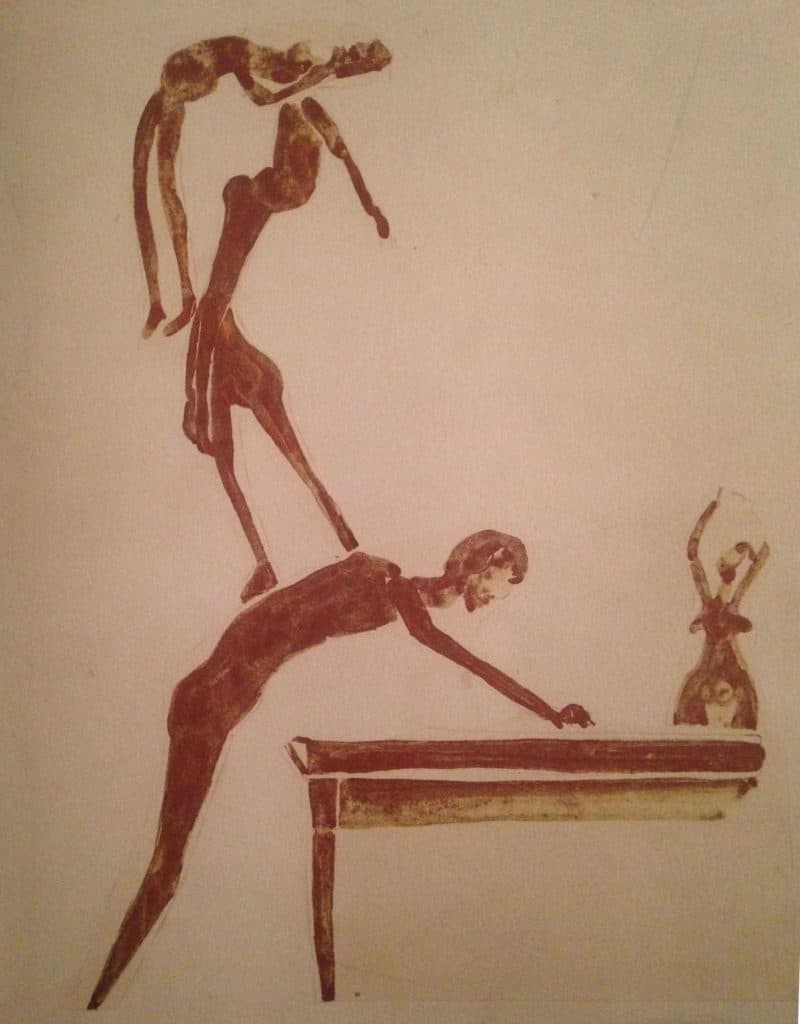

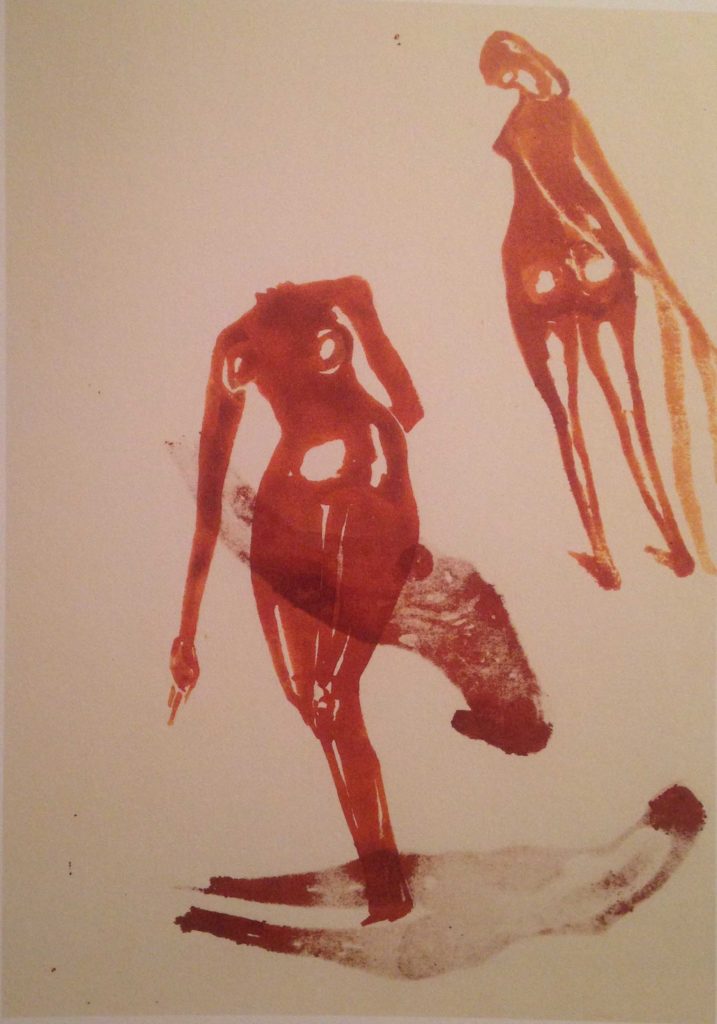

Beuys’s figures do not appear in a stable manner in any kind of detailed, particular context. The characteristic of Beuys’ figures in his drawings is that man and animals are existentially free in the surrounding nothingness, out in the open, in the large incompleteness, as anonymous protagonists of universal mankind.

In his works of the 1950s, the female figure pervades, and the male figure is almost entirely absent. Resisting against a patriarchal society focused on initiating an “economic miracle” after the war, Beuys pushed for an opposite type of recovery, favouring the spiritual and natural through a search for the qualities embodied in the female archetype. For Beuys, the female figure functioned represented a bridge between the earthly and unearthly worlds.

Animals, Legend and Folk-Tale

The animals in Beuys’s drawings similarly act as a bridge between the earthly and unearthly worlds. Animals that frequently return in his drawings are stags, swans, elk, and bees, all filled with symbolic meaning. The animal closest to Beuys was the stag, a traditional emblem of the Northern forest which often appeared in German legends. The stag, for Beuys, was a spirit guide or “accompanier of the soul.” Stags often appear as wounded in his drawings, which according to Beuys was the result of violation and misperception.

Another popular animal in his drawings was the swan, his most personal totem as it is the symbol of the town of his birth, Kleve. The swan is a mediator between different realms, embodying the unity of the female and male capacities in one being.

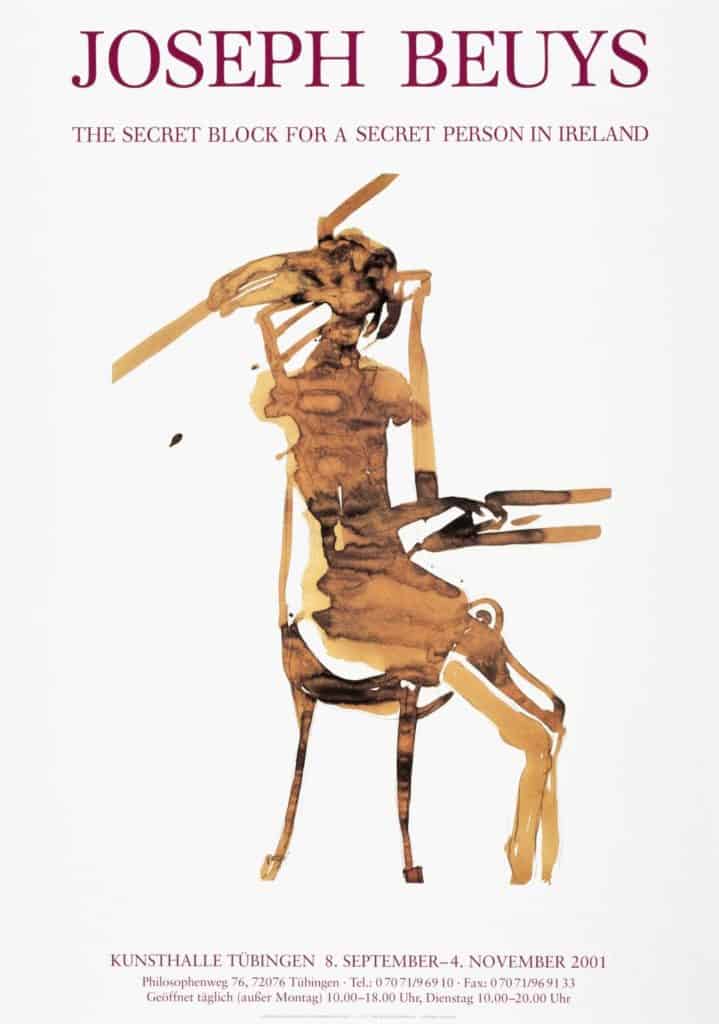

The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland and The Ulysses Sketchbooks

In 1974, Beuys assembled and titled his drawing project The secret block for a secret person in Ireland. This project consists of over 400 drawings set aside by Beuys over the years to form a comprehensive group of works. There is a strong sense of process and metamorphosis in these deeply narrative drawings.

A similar pictorial language can be found in a series of six sketchbooks known as The Ulysses Sketchbooks (1959-1961). Using James Joyce’s Ulysses as a foundation for these drawings, the sketchbooks present an overview of Beuys’s formal and thematic vocabulary, creating a whole universe of signs and systems. The drawings in this series evoke natural processes of circulation, growth, and transformation.

Braunkreuz

At the start of the 1960s, the Braunkreuz (brown cross) medium started to appear in the drawings of Beuys. This represents a distinctive change in his drawings, as he started to move from introversion to a more assertive voice and more monumental scale. With Braunkreuz, Beuys began to push the borders of drawing, sculpture and performance. It can be seen as the culmination of Beuys’ interest in painting with unusual materials, and shows how he liked to treat his media as substances with independent values. Braunkreuz came to function as an autographic medium linking life and art, encompassing a complex constellation of terms and references to Christianity, the occult, war or disaster relief, but also to German militarism and Nazism.

Beuys’s use of brown paint for his Braunkreuz work, like his use of fat and felt, was criticized by people accusing Beuys of making “ugly art.” Beuys rejected conventional notions of culture and aesthetics, in line with the modernist tradition of “anti-art.”

The Last Drawing Project of Joseph Beuys

Beuys’s last major series of drawings, Ombelico di Venere – Cotyledon Umbilicus Veneris consists of a group of fourteen pressed plant drawings made in 1985, a year before he died. With these drawings, Beuys returned to the genre of botanical collage, one of his earliest passions. As such, the artist chose to return to his beginnings for his last important drawing project, creating a cyclical phenomenon representative of his belief in existence as a continuum of births and rebirths. In his own words: “The drawing holds special meaning for me, because in the early drawings… everything is in principle already foreshadowed.”

Relevant sources to learn more

If you would like to read more about the drawings of Joseph Beuys, see:

MoMA Publication Thinking is Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys

Staatliche Kunsthalle Karlsruhe Publication: Joseph Beuys: Zeichnungen