Interviews

Interview: ArtistPaco Pomet

by Artland Editors

On the occasion of Paco Pomet’s solo exhibition, No Places, at Galleri Benoni in Copenhagen we sat down with the artist to discuss his work and some of the the ideas that inform it.

Hi Paco, thanks for joining us. You have mentioned random photographic sources that you use as a starting point, especially ones that have a strongly ‘vintage’ feel about them. What features or characteristic does an image have to possess for you to use it as a ‘way in’ to your image or aesthetic?

I am really fond of photography from the first half of the twentieth century. That period shows us a genuine enthusiasm about new inventions (photography and cinema, the car, the plane, the radio, the telephone…), a time more naïve, more perplexed and fascinated by such things, before mercantilism and advertising flooded everything. The photographs that I like to recover from that time are a great source for my paintings.

I am interested especially in documentary, press and amateur photography (also including photographs taken by myself deliberately for a painting), and family photograph collections. The more rushed or inexperienced the photographer (including myself) the greater is the photographic radicality and distance from the visual and compositional codes of painting. The subjects that may appear in these photographic sources can be very varied, and any given motif can be susceptible to a new pictorial use, or the switch or spark that creates a new idea.

When you seek to disrupt the photographic image source image, what condition or state do you hope to create for the viewer?

In the resulting images I am interested in constructing a new visual order. I try to dismantle the conventional codes that we use to read an image and try to propose others. But I don’t pretend to offer the viewer alternative codes of interpretation for the newly conceived images. I propose some hints as starting points but it is the viewer that has to build his own semantic routes through the painting. Ultimately what I would like to achieve is that painting could work as a mirror, reflecting to the viewer his own personal thoughts, fears and desires.

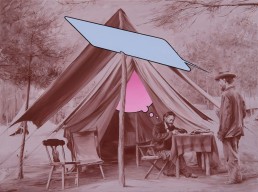

The imagery you add that changes the meaning and context of the original often has a kind of comic book, or sci-fi / B-movie aesthetic. What kinds of narratives are you seeking to portray?

I like to play with different cultural motifs and influences. I try not to classify them in high or low culture. I have always liked comic books and sci-fi / B-movie aesthetics and sometimes it is irresistible to refer to them when composing an image. Combining these sources with other more serious or ‘high brow’ motifs can bring surprising, unexpected and puzzling results. In some of my paintings, working with this imagery is like a game, a really healthy and entertaining visual adventure where I can be very surprised myself, and when this happens the act of painting becomes really amusing.

In your paintings we can see influences as diverse as Surrealism, a magic realism akin to Mark Tansey’s work, and even the kind of California counter culture embodied by the work of Robert Williams. Is there an artist or artists that have most inspired you?

The surrealists of the first half of the twentieth century are a big influence for me. Dalí, Buñuel and especially Magritte have been very important in the way I understand and enjoy art. There are some contemporary artists that have reassumed surrealism in a very particular way that seems witty and challenging. Tansey, as you have mentioned, is one of them. He is very allegorical and analytical, which is not common in a contemporary artist, and that is a great attribute. I also like the work of Neo Rauch and Friedrich Kunath, to give two more examples. The compact body of Rauch’s work is impressive, and his imagery is always a real challenge. One could stare at his painting for ages and they would not loose their strength and mystery. Kunath’s work is more joyful and varied, very unexpected most of the time. His revision of Romanticism along with his unpredictable use of popular culture motifs makes his work very unique and one of the most intriguing that I have found recently. I specially appreciate the humor that some of his works convey, for I think this is one of the most valuable features that art can give us.

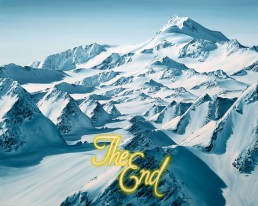

Often the scenic backdrop for your compositions is an expansive natural view, frequently a ‘sublime’ American landscape of the West. Does this choice have a particular meaning or dramatic possibility for you?

I have always loved landscapes and especially the pictorial representation of such that is typified by the Romantic period of the early nineteenth century. The concept of ‘sublime’ was very prevalent in German aesthetics of that time, and painters like Caspar David Friedrich represented very accurately this feeling. But there is a representational vein that has a beautiful and impressive approach towards landscape: the one that photography and cinema brought to visual arts at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth. Artists like Ansel Adams are a clear example of this. In recent years, I have used archival photography of landscapes found in different sources. One of them is The City of Vancouver Archives, a huge stock of photographs open to public access, in which I found outstanding photos, devoid of any artistic touch, that are perfect visual sources to work from.

I have been interested lately in conveying a melancholic impression (related to the aforementioned sublime) that a landscape can provoke. On the majority of occasions this experience is translated into a joy, a reverential communion before the ecstatic beauty of the spectacular unfolding of nature. It would be like a commemoration of ‘the figure and the landscape’. But, in others, this melancholic experience is tinged with hurt before the immensity of the world along with the consciousness of lightness, smallness, and finitude of one’s self-existence. In these cases, the landscape reveals itself as a sinister scenario where the changes in light conditions I paint are filled with threatening intentions, showing the disturbing vastness of the space as well as the awareness of the inevitable passage of time.

Clearly humour and wit plays an important role in your imagery. Can you explain how important this component is in your work?

Humor has always been present in my work, but it is a difficult genre. It is hard to hit the target and as many people in the comedy business say: “comedy is the hardest”. As time has passed and I have moved away from youth, skepticism and hopelessness have gained ground in the way I see the world. It is inevitable. I have always been (and I think I still am) a quite optimistic person but this personal predisposition can be mitigated by the stubborn presence of reality. I happen to like realism precisely because I tend to be very observant, even though I am more and more critical with reality. I think that as a result of this the humorous character in some of my works is somehow turning bitter and more caustic. A slightly misanthropic drift has imbued the themes of many of my works lately, however a bright and clean humorous strike can also appear dressed up in oil paint at any moment.

Yes, it would have been more accurate of me to speak of a humor that has an often sardonic tone to it! Thanks for your insights and for your time Paco. It has been fascinating to hear about your paintings directly from you. We wish you every success with your exhibition and future projects.