Articles and Features

Art Movement: Conceptual Art

By Shira Wolfe

“The ‘purest’ definition of conceptual art would be that it is an enquiry into the foundations of the concept ‘art'”

Joseph Kosuth

Conceptual Art definition:

Unpacking the term Conceptual art is not quite as straightforward as other art movements. It’s easy to get confused by the different ways in which the word is used. While it most commonly refers to the art movement between the 1960s and 1970s that emerged in the United States, there are several other ways of understanding it. What exactly does this word connote? When was Conceptualism an art movement, and does it still exist? In his comprehensive book Conceptual Art, art historian Paul Wood distinguishes between the different ways the term is used:

1: Conceptualism is often used as a negative term for what people dislike about contemporary art which revolves around the concept.

2: Conceptualism refers to the Anglo-American art movement that blossomed in the 1960s and 1970s. The idea, planning and production process of the artwork were seen as more important than the actual result.

3: A more expanded notion of Conceptualism holds that men and women in all corners of the world had been working in a conceptual manner since the 1950s on themes ranging from imperialism to personal identity. In this sense, Conceptualism becomes a Global Conceptualism.

This article will explore both the Anglo-American and the global Conceptual art movement.

What is Conceptual Art?

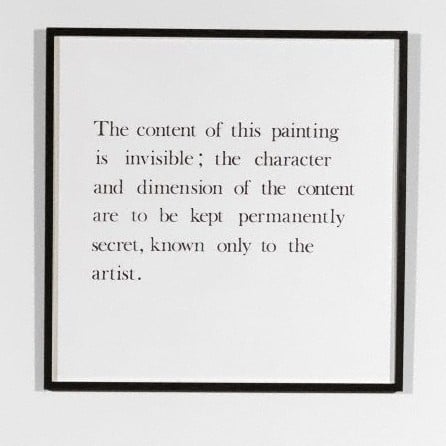

Conceptual art emerged as an art movement in the 1960s, critiquing the previously ruling modernist movement and its focus on the aesthetic. The term is usually used to refer to art from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s. In Conceptualism, the idea or concept behind the work of art became more important than the actual technical skill or aesthetic. Conceptual artists used whichever materials and forms were most appropriate to get their ideas across. This resulted in vastly different types of artworks that could look like almost anything – from performance to writing to everyday objects. The artists explored the possibilities of art-as-idea and art-as-knowledge, using linguistic, mathematical, and process-oriented dimensions of thought as well as invisible systems, structures and processes for their art.

Key dates: Mid-1960s to mid-1970s

Key regions: USA, Soviet Union, Japan, Latin America, Europe

Key words: Concept, idea, language, transitional, political, postmodernist art

Key artists: Sol LeWitt, Joseph Kosuth, Mel Bochner, Hanne Darboven, Jan Dibbets, Hans Haacke, On Kawara, Lawrence Weiner, Ian Burn, Mel Ramsen, Yoko Ono, John Baldessari, Art & Language group, Marina Abramović

The origins of Conceptual Art

Although Conceptual art was first defined in the 1960s, its origins trace back to 1917, when Marcel Duchamp famously bought a urinal from a plumber’s shop and submitted it as a sculpture in an open sculpture exhibition in New York, for which he was on the selection committee. The jury rejected the work, deeming it immoral, and refusing to accept it as art. Duchamp’s questioning of where the boundaries of art lie and his critique of the art establishment paved the way for Conceptual art.

Fluxus

In the early 1960s, the term ‘concept art’ was already in use by members of the Fluxus movement like Henry Flynt. Fluxus was a group that embraced artists from Asia, Europe and the United States. The movement was all about creating an open attitude towards art, far removed from modernism’s exclusivity. Fluxus artists were interested in broadening the range of reference of the aesthetic towards anything, from an object to a sound or an action. Famous Fluxus artists include Yoko Ono, who was active in a wide range of Fluxus activities in both New York and her native Japan, and Joseph Beuys in Germany. Though not always exactly deemed part of the Conceptual art movement, Fluxus is without a doubt one of its influences. It was an important tendency on the same wavelength as Conceptualism, and its artists are often regarded as Conceptual artists.

Frank Stella’s Black Paintings

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Frank Stella created his series of Black Paintings, which marked a crucial point of fracture between Modernism and Counter-Modernist practices. This series of works would lead to the emergence of Minimalist and Conceptual art. The point of these works was to literally emphasise and echo the shape of the canvas, getting the work off the wall and into three-dimensional space. This was an attack on Modernism that gave rise to something that was entirely anti-form. The work of art became about actions and ideas, and from this point onwards, it seemed like the floodgates had opened and artists had moved into totally new territory. Modernism had really come to an end.

Sol LeWitt’s Paragraphs on Conceptual Art

Sol LeWitt’s 1967 article ‘Paragraphs on Conceptual Art’ in Artforum was one of the most important writings on Conceptualism. The article presented Conceptual art as the new avant-garde movement. In fact, the term ‘Conceptual art’ appeared for the first time in this article. The opening of LeWitt’s article has come to constitute the general statement of a Conceptual approach: ‘In Conceptual art the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work. When an artist uses a Conceptual form in art, it means that all of the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes a machine that makes the art.’

Famous Conceptual Art artists

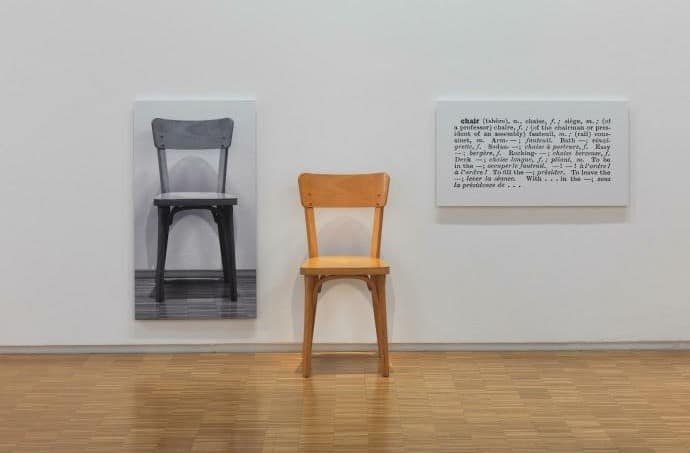

Joseph Kosuth

Conceptual art as a clear movement started emerging in the late-1960s. In 1967, Joseph Kosuth organised the exhibitions Nonanthropomorphic Art and Normal Art in New York, where works by Kosuth himself and Christine Kozlov were shown. In his notes accompanying the exhibition, Kosuth wrote: ‘The actual works of art are the ideas.’ In the same year, he exhibited his series of Titled (Art as Idea as Idea). This series of works consisted not of visual imagery, but of words that were at the core of the debate surrounding the status of modern art – ‘meaning’, ‘object’, ‘representation’, and ‘theory,’ among others.

Art & Language Group

Meanwhile in England, the Art & Language Group were investigating the implications of suggesting more and more complex objects as works of art (examples include a column of air, Oxfordshire and the French Army). The first generation of the Art & Language Group was formed by Terry Atkinson, Michael Baldwin, David Bainbridge and Harold Hurrell in 1966-67. Later, the group also expanded to the USA. In 1972, they produced the Art & Language Index 01 for Documenta V. This was an installation consisting of a group of eight filing cabinets containing 87 texts from the Art-Language journal.

Lucy Lippard’s Six Years

Lucy Lippard’s book Six Years, covering the first years of the Conceptual art movement (1966-1972), came out in 1973. In keeping with the confusing and complex nature of Conceptual art, the American artist Mel Bochner condemned her account as confusing and arbitrary. Years later, Lippard would argue that most accounts of Conceptualism were faulty and that nobody’s memory of the actual events related to the development of Conceptual art could be trusted – not even the artists’.

Conceptualism in Europe

As stated before, Conceptualism was not only important in the USA and England, but was also widely explored and developed in other parts of the world, where the work was often far more politicised. In France, around the time of the 1968 student uprisings, Daniel Buren was creating art that was meant to challenge and critique the institution. His aim was not to draw attention to the paintings themselves but to the expectations created by the art context they were placed in. In Italy, Arte Povera emerged in 1967, focused around making art without the restraints of traditional practices and materials.

Conceptualism in Latin America

In Latin America, artists opted for more directly political responses in their work than Conceptual artists in North America and Western Europe. The Brazilian artist Cildo Meireles reintroduced the readymade with his Insertions into Ideological Circuits series (1969). He would interfere with objects from systems of circulation like bank notes and Coca-Cola bottles by stamping political messages onto them and returning them into the system like that.

Conceptualism in Soviet Union

In the Soviet Union, art critic Boris Groys labelled a group of Russian artists active in the 1970s the ‘Moscow Conceptualists’. They mixed Soviet Socialist Realism with American Pop and Western Conceptualism.

Contemporary Conceptual Art and Conceptualism

Conceptualism in contemporary practice is often referred to as Contemporary Conceptualism. Contemporary Conceptual artworks often employ interdisciplinary approaches and audience participation, and critique institutions, political systems and structures, and hierarchies. Artists who clearly use various techniques and strategies associated with Conceptual art include Jenny Holzer and her use of language, Sherrie Levine and her photographic critique of originality, Cindy Sherman and her play with identity, and Barbara Kruger’s use of text and photography.

As we’ve explored the complex and extensive history and presence of Conceptual art, several things come to mind. One of its greatest strengths was taking the responsibility to truly investigate the nature of art and institutions. At times, it was an art of resistance to the dominant order. At other times, it was a cynical mirror held up to the art world, or a deeply philosophical undertaking. Many artists despised being put in the box of Conceptual art, as they despised being put into any box. Yet, we have attempted to draw certain lines between various artists, events and thought systems that circled around a similar orbit for some time and which can be better understood under the umbrella of Conceptualism.

Conceptual art FAQ

What does conceptual mean in art?

When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all of the planning and arrangements are made beforehand, and the execution is a more a shallow process. In conceptual art, the process behind the work is more important than the finished artwork.

What are the characteristics of Conceptual Art?

Conceptual Art is mainly focused on “ideas and purposes” rather than the “works of art” (paintings, sculptures, and other valuable objects). It is characterised by the use of different media and supports, along with a variety of temporary everyday materials and “ready-made objects”.

Who is the father of Conceptual Art?

Marcel Duchamp is often known to be the forefather of Conceptual Art. He is best known for his readymade works, like Fountain, the famous urinal that he designated as art in 1917 and that is seen as the first conceptual artwork in art history.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about Art Movements and Styles Throughout History

Piero Manzoni and his Merda d’Artista: Can shit be art and who decides?

Learn more about Conceptualism Before, During, and After Conceptual Art by Terry Smith

Learn more about the Art Term on Tate Publishing