Articles and Features

Piero Manzoni and his Merda d’Artista: Can shit be art and who decides?

“I should like all artists to sell their fingerprints, or else stage competitions to see who can draw the longest line or sell their shit in tins”

By Lauren Gee

Who was Piero Manzoni?

Piero Manzoni was born in Soncino, Italy in 1933 against the backdrop of Mussolini’s fascism. He was of noble descent; his father Egisto, was a count, rendering his full title Il Conte Meroni Manzoni di Chiosca e Poggiolo. He was part of a large family with four siblings; two brothers and two sisters, of which he was the eldest. During his early years he was sent to the infamous Jesuit school Liceo Leone XIII, though this education did not include any specific artist training to speak of. Following the death of Manzoni’s father in 1948 by heart attack, (a fate that would later befall Manzoni himself at the young age of 30) Manzoni went on to pursue art more seriously. He began painting at seventeen, starting with abstract and gestural works typical of the post-war period, but his style was to change greatly. Ultimately he become a leading pioneer of conceptual thinking in Modernist practice and an infamous iconoclast, with his shocking use of materials culminating in the controversial Merda d’artista, an act of artistic sacrilege that confirmed his place in the annals of the avant-garde.

When was Piero Manzoni Working?

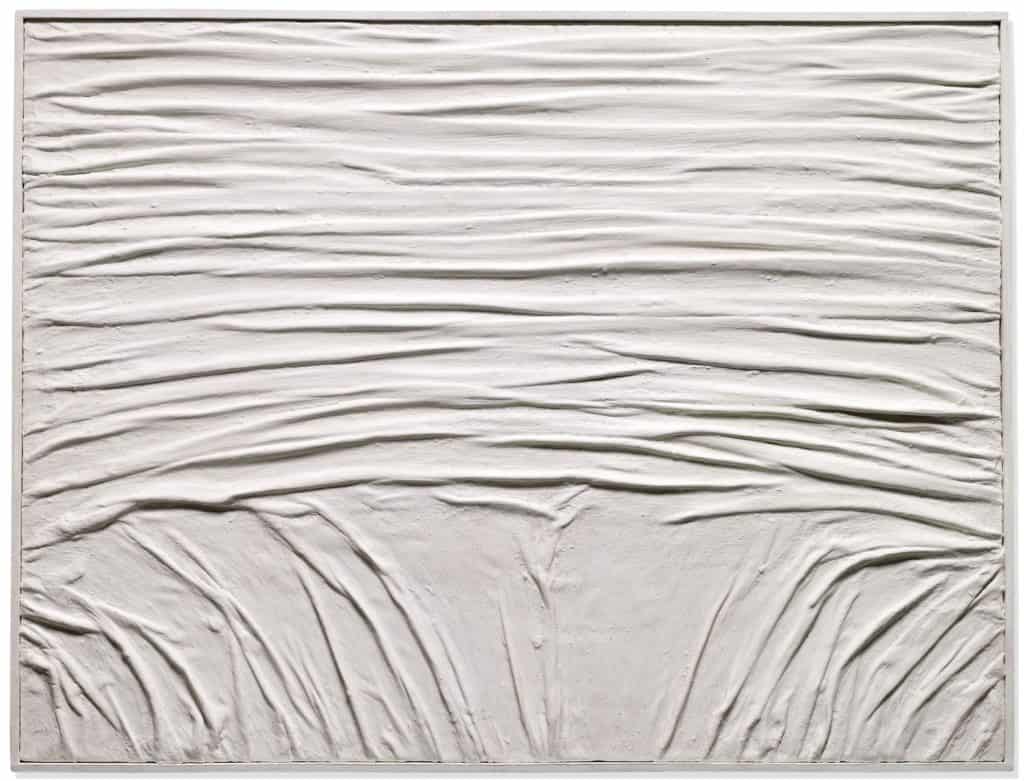

Manzoni made art at a critical time. World War II had transformed Italy greatly, with the subsequent rebuilding resulting in a massive economic boom. Coined ‘The Italian Miracle’, Italy’s economic and social development grew the country into an industrial stronghold. Alongside his contemporaries Manzoni made art which navigated and reacted to the shift in Post war Europe, changes which had left many unable to recognise the humble neighbourhoods they had grown up in. His work has been read by many as a critique of the mass production and consumerism that had taken over Italy, an erstwhile agrarian and humble economy. His choice of materials ranged from rabbit fur to cotton, and eventually his own excrement, directly challenging the finished goods and production values of the factory and production value in their re-appropriation of everyday objects. Merda d’artista can be seen as one of the most obvious examples of this opposition—he directly references a manufactured product of the factory and even utilises a vessel emblematic of this production process, the tin can, filling it with his own excrement, and thus yielding a protest to the industrialisation that had seized his country.

Artists that influenced him

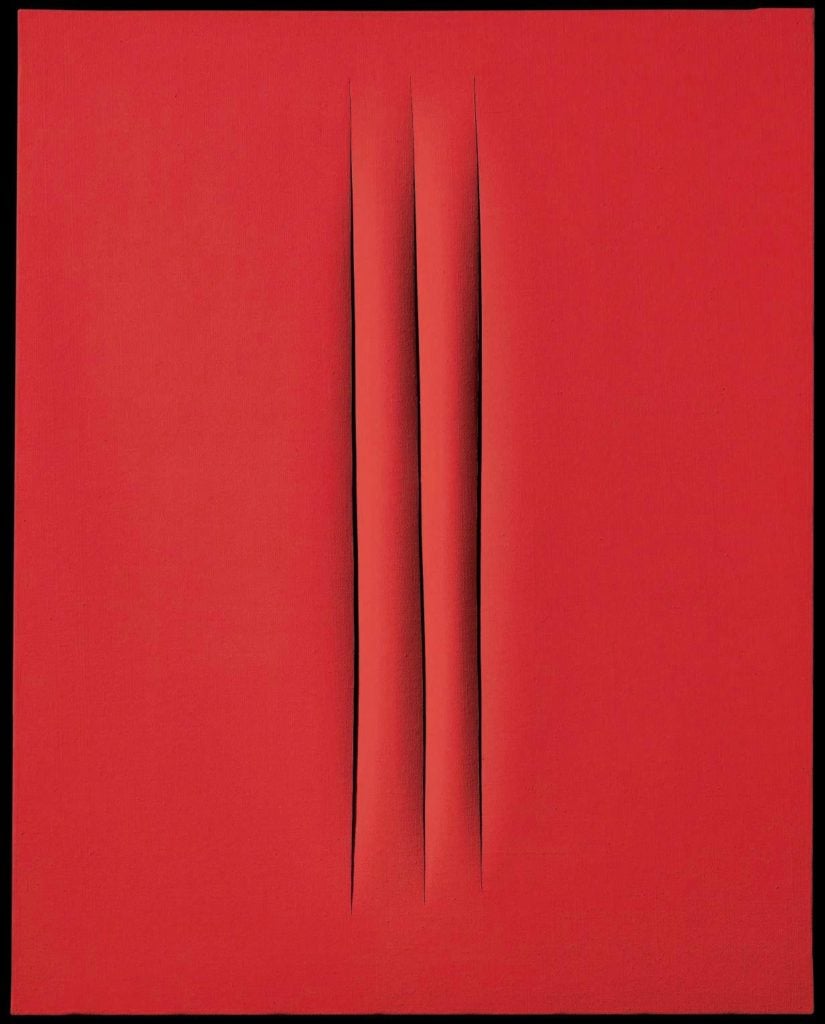

It is clear to see the art and lineage of artists that influenced Manzoni, with the Merda d’artista channelling both the Duchampian gesture of the readymade and its inherent critique of the high art object. Despite having no formal art education in his early life, Manzoni did study for a short time in Milan at the Brera Academy where his contact with other artists would have also helped to shape his practice. He became friends with fellow artist Argentine-Italian Lucio Fontana, a painter most well known for his bright canvases pierced by deep slashes, also a direct challenge to the received ‘values’ of the medium of painting, and with an ideology that had a close kinship with Manzoni’s own. It was through Fontana that Manzoni became introduced to the International Nuclear Art Movement led by Italian avant-garde artist, Eaismo. In 1948 they produced a manifesto in which their stance against the industrial use of nuclear power was established. Manzoni also retains a longstanding comparison to French artist Yves Klein, part of this same movement. Klein also painted highly conceptual monochromatic canvases as well as producing more conceptual pieces such as ‘The Void’ a work consisting of an empty gallery. In this sense Manzoni and Klein were similar in that their work was constantly pushing the boundaries of what could be referred to and celebrated as art.

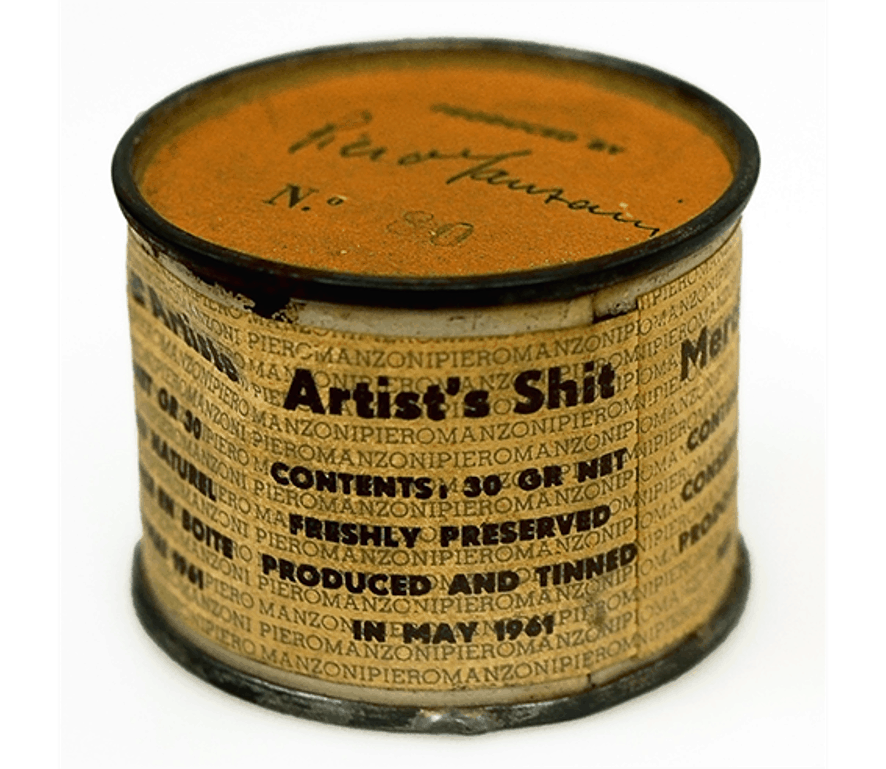

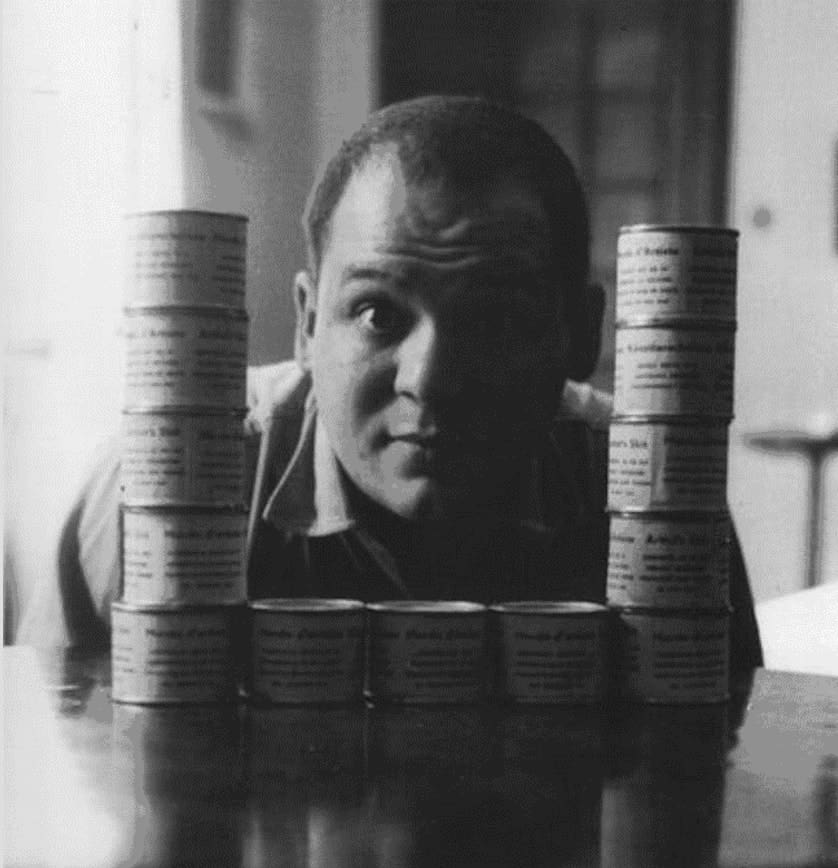

The shit in a can

Manzoni produced Merda d’artista at the end of his career in 1961, two years before he passed away. While living in Milan he made the series, comprised of ninety cans of shit, each numerically labelled, as one would expect a set of prints to be, with German, French and English titles describing the cans as ‘Artist’s shit’. In a letter to fellow artist and friend Ben Vautier, he humorously speculated that ‘if collectors want something intimate, really personal to the artist, there’s the artist’s own shit, that is really his.’ Though said in jest, his critique of the art market and those invested in it was a real and integral manifestation of his thoughts at the time, sitting at the core of much of his work. Before Merda d’artista he had made ‘Artist’s Breath’ in which he blew up a red balloon and then framed it as a piece of art. Through this declaration of what could be considered art he further challenged the way art was seen. In using his own breath and then own excrement, he inserted his own physical being into his work in a very literal and specific way, also asserting the artist’s cult of personality as the ultimate arbiter of what could, and could not, be deemed art. At the time of its making it was recorded that he sold one can to Alberto Lùcia for 30 grams of 18-carat gold. In more recent years examples from the original edition have made some eye watering sums at auction, including at auction in Milan in 2016 where one of the tins sold for a new record of €275,000.

Is it Art?

Manzoni follows a long conceptual tradition in which the viewer is challenged to re-evaluate their preconceptions or perspective about familiar objects. The work can be likened to Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’ in which he appropriated a urinal deeming it a fountain rather than vernacular low-grade bathroom porcelain, and also to René Magritte’s “Ceci n’est pas une pipe” in which he claimed a painting of a pipe, was in fact ‘not a pipe’. Duchamp and Magritte, like Manzoni, challenge what is both being shown and perceived through the framing, presentation and titling of the work. However, Manzoni goes one step further in simply naming his piece ‘Artist’s Shit’, an ultimate act of defiance fully realised. The stark transparency in which he presents the work shows no effort to conceal the contents of the work, but rather provoke and confront the set of expectations we bring to art and the gallery space.

Piero Manzoni and The Myths of the Merda

It is much disputed as to whether the can does in fact contain Manzoni’s shit, with some sceptics believing it to contain plaster, though this theory can never be tested since the act of opening a can to check will render it valueless as a commercial entity. Though the work seems a natural fit in terms of the artist’s ideas about art and materiality, it has been said it was made in reaction to a specific statement made by his father in which he was told his son, ‘Your work is shit’. His father supposedly also owned a canning factory thus defining Merda d’artista as a perfect rebuttal to his closest critic. When Manzoni died in 1963, it is said that his friend and artist Ben Vautier signed his death certificate, claiming that it was now a piece of art, a fitting final word for an artist who had sent his life subverting what could and could not be considered art.