Articles and Features

Marcel Duchamp: The Forefather of Conceptual Art

By Shira Wolfe

“Painting has always bored me, except at the very beginning, when there was that feeling of opening the eyes to something new.”

Marcel Duchamp

Marcel Duchamp is regarded as one of the crucial figures in the development of modern and contemporary art and his body of work spanning from painting to the plastic arts has had a huge impact persisting to this day. The artist-provocateur par excellence, not only did he provide a personal interpretation of Cubism, but also greatly influenced Dadaism and Surrealism, paving the way for Conceptual Art with the aim of putting “art back in the service of the mind.”

Biography of Marcel Duchamp – From Art to Anti-Art

Marcel Duchamp was born in 1887 in Blainville-Crevon in Normandy, France, and grew up in a creative family. His childhood home was filled with art by his grandfather – Duchamp later said of this time: “When you see so many paintings, you’ve got to paint.” At the age of 17, he decided to become an artist. Three of his siblings (there were seven children in total, one of which died as an infant), also ended up as successful artists.

The young Duchamp explored a variety of styles, but nothing could satisfy him. By the age of 25, he realized the only direction he could possibly take was deep into unknown territory. His maturity as a painter coincided with the historic moment of the 1910s when revolutionary changes were taking place in music, literature, and the visual arts, and a break with the past was made through the shattering of familiar structures (think of the important contributions made by writers, composers, musicians and artists such as Joyce, Stravinsky, Schönberg, Picasso, Braque, and Kandinsky). Duchamp’s need to move into experimental territories, away from the painting that had started to bore him, can be seen as a move from art to anti-art. He wanted to get away from the physical aspect of painting and was interested in ideas, not merely visual products.

Duchamp and the early-20th-century avant-garde

Duchamp made memorable contributions to avant-garde movements such as Cubism and Dadaism and had an impact on Surrealism.

Surrealism

Though he was never a formal member of Surrealism, the artist did design the International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris in 1938, a wild show where he transformed the central hall into a grotto carpeted with leaves and roofed with coal sacks. In doing so he created a happening, forcing the viewer to become involved in the surroundings.

Cubism

Although Marcel Duchamp’s contribution to Cubism was short-lived, his Nude Descending a Staircase was an important Cubist work that made waves at the 1913 New York Armory Show. This was the show where Man Ray encountered Duchamp’s work, starting a lifelong friendship between the two artists.

Dadaism

Inspired by his friend and fellow artist, Man Ray eventually moved to Paris and submerged himself in the Parisian Dadaist movement, while Duchamp himself would come to move to New York during World War I. Duchamp naturally connected to Dada due to his great sense of humor and his anti-establishment and anti-art tendencies, and shared this with his close friend, the artist Francis Picabia: both were occupied with keeping a “corridor of humor” open through the density of art theory. Despite Duchamp’s connection with the Dadaist activities, he never really belonged or wanted to belong to any particular group and was really his very own, one-man art movement, influencing all others around him and after him. His studio was known for its spartan interior with little more than a table and chess set (all his life, Duchamp was an avid chess player) and a chair. It is in this period, around 1913, that the first readymade objects began entering Duchamp’s studio.

Marcel Duchamp and the Readymade

The first readymade that Duchamp created was his Bicycle Wheel (1913). It consists of the front wheel of a bicycle, mounted upside down on a kitchen stool so that the touch of a hand can make it spin. Another object in 1914 was a galvanized iron rack for drying wine bottles, to which he signed his name and placed it in the context of art. These objects were quite attacks on the whole tradition of Western art. They received their name, the “readymade”, in 1915 and the Surrealist leader André Breton defined them in 1934 as: “manufactured objects promoted to the dignity of objects of art through the choice of the artist.” Duchamp was very careful not to let his readymades turn into an artistic activity: he limited the number of readymades he made yearly and never sold them. When three of his readymades were included in a 1916 exhibition at the Bourgeois Gallery in New York, he insisted that they should be hung from a coat rack at the gallery door. To his delight, nobody even noticed their presence in the gallery.

In 1917, the Society of Independent Artists, which Duchamp had helped to found in New York, put on an exhibition that was open to any artist who paid the six-dollar fee. There was no jury and no restriction on what could be shown in the show. Duchamp decided to test this supposed artistic freedom of the show. He paid the fee and entered a porcelain urinal which he titled Fountain under the artist name “R. Mutt”. The hanging committee then refused to exhibit this object as a sculpture, spurring Duchamp to write a succinct definition of the readymade work of art. He wrote:

“Whether Mr. Mutt with his own hands made the fountain or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under a new title and point of view – [he] created a new thought for that object.”

Marcel Duchamp

This act and statement by Duchamp would forever change the possibilities of art, and paved the way for conceptual art.

The artist became a permanent resident of New York over time. There, the art world developed rapidly and eventually centered around the post-war New York School of Abstract Expressionists. When the dealer Roland Knoedler once asked Man Ray to approach Duchamp with the idea to return to painting (Knoedler offered him $10,000 a year for one painting a year by Duchamp), his response was that he had accomplished what he had set out to do, and did not care to repeat himself. He instead occupied himself with his suitcase museums, the boîtes-en-valises, with which he focused on the survival of his ideas. His influence on the new generation of artists was immense, yet indirect. He represented to them an unbridled sense of experimentation and iconoclasm, something that his name and legacy still carry to this day.

“I don’t believe in art. I believe in artists.”

Marcel Duchamp

Most Famous Artworks by Marcel Duchamp

We take a look at the most iconic works by Marcel Duchamp, ranging styles and media from painting to sculpture and installation.

Nude Descending a Staircase, 1912

The creation of his Cubist masterpiece Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 marked the end of the artist’s formal affiliation with the Puteaux Cubists, a group of Cubist artists who rebelled against the casual or intuitive style of Picasso and Braque and who reacted violently to this new piece. A year later, when the work was exhibited at the New York Armory Show, American critics were outraged, ridiculing the painting. One of the things that people took offense to was the fact that it was not typical for a nude to be depicted in movement – usually, they would be depicted standing or reclining, and it had never before occurred that a nude was painted while walking down the stairs towards the viewer. Forty years after painting it, when it had long been recognized as a masterpiece, Duchamp said: “There’s nothing to be ashamed of in it, no… It is posterity, even if only a 40-year posterity, that really makes a masterpiece.”

Fountain, 1917

Duchamp bought an ordinary urinal in 1917, signed it “R. Mutt” (as a pun referring to the Mott manufacturers of toilets), and entered it into the exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists. While it caused outrage among the board members and was refused to be accepted as art in the exhibition, the piece became legendary. Photographs taken by Alfred Stieglitz immortalized the readymade, as well as 16 replicas that were made in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, it is known as the very foundation of contemporary art.

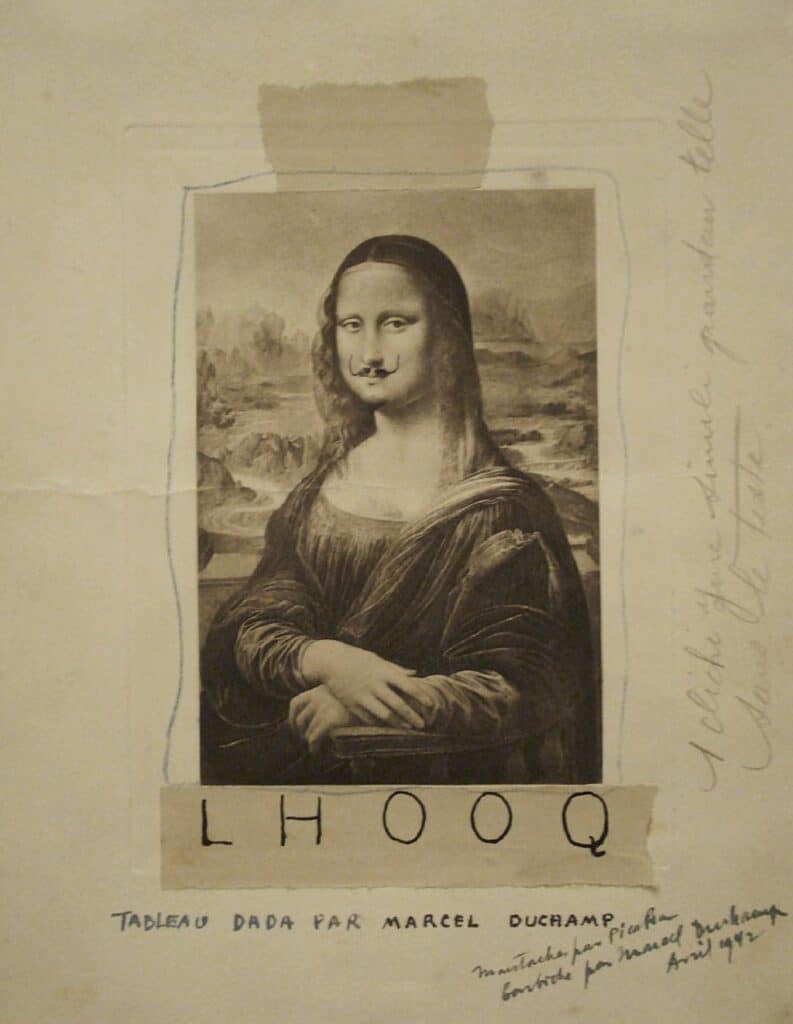

L.H.O.O.Q. (Mona Lisa), 1919

In 1919, the artist parodied the Mona Lisa by adding a mustache and goatee to a cheap reproduction of the painting. Then, in keeping with his keen sense of humor, he added the inscription L.H.O.O.Q., which, when read out lout quickly in French, sounds like “Elle a chaud au cul” (“she has a hot ass”). This “assisted readymade” was also the cover for an edition of Francis Picabia’s magazine 391.

The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-1923

Marcel Duchamp worked on The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even, also known as The Large Glass, between 1915 and 1923 until he formally declared it “unfinished”. He described it as a “hilarious picture”, as the erotic encounter between a bride and her nine bachelors. André Breton spoke of it as “the trophy of a fabulous hunt through virgin territory, at the frontiers of eroticism, of philosophical speculation, of the spirit of sporting competition, of the most recent data of science, of lyricism, and of humor.” The work was executed on two panes of glass, using materials like lead foil, fuse wire, and dust, and an important part of it was the acceptance of chance. After its first exhibition, the glass was cracked during the transportation, and Duchamp chose to leave several of the cracks in the glass intact instead of fixing them. Many critics read the piece as an exploration of female and male desire, and Gilles Deleuze claimed it to be the celibate machine, consisting of auto-erotic consummation.

Today, the piece is on view at the Philadelphia Museum of Art beside The Green Box, Duchamp’s notes on this mysterious and thought-provoking work of art.

Relevant sources to learn more

10 Controversial Artworks That Changed Art History