Articles and Features

Dreaming Through the Camera:

The Visionary Photographs of Man Ray

By Shira Wolfe

“Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is Dada, and will not tolerate a rival.”

Man Ray

Who was Man Ray?

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1890, Man Ray was the oldest child in a family of recently immigrated Russian-Jews. In 1897, the family moved to Brooklyn, New York and changed their surname to Ray in 1912, in response to the anti-Semitism prevalent at the time. Emmanuel’s nickname was Manny, and he decided to change his first name to Man, which lead to the name he became known for as an artist, Man Ray. Though he was very private about his family and personal history and wished to disassociate himself from his family background, his family’s tailoring business left a mark on his art as all kinds of items related to tailoring (flat irons, dummies, needles, etc.) were to appear in his work throughout his career. Best known for his pioneering photography but prolific in a variety of media, Man Ray would become a major contributor to Dadaism and Surrealism.

Biography of Man Ray

While living in New York, Man Ray attended the notorious 1913 Armory Show, where he encountered Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No 2 (1912). Ray was inspired and began a lifelong friendship with Duchamp. This was also the beginning of his involvement in the Dada movement. Abandoning conventional painting, he started to make objects and to develop unique mechanical and photographic image-making methods. His works began to depict the movement of figures and he also explored the making of ready-mades. Another influence was Alfred Stieglitz, who introduced Ray to the medium of photography, which led to a new field of experimentation. In 1920, Ray and Duchamp published the first and only issue of New York Dada, and in 1921, Ray moved to Paris. He had just separated from his first wife and felt Dada could not develop in New York, saying: “Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is Dada, and will not tolerate a rival.”

“I have finally freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself.”

Man Ray

Shortly after settling in the Montparnasse district in Paris in 1921, Ray had his first solo exhibition in Paris. He met the French composer Erik Satie while setting up his exhibition, and the two went for drinks at a corner café. Upon leaving the café, Ray’s eye fell on a shop selling household appliances and with Satie’s help (the newly arrived American spoke no French at the time) he purchased a flat iron, a box of tacks and a tube of glue). Back at the gallery he glued a row of tacks to the smooth surface of the iron, titled it The Gift, and added it to the exhibition. It was the first Dada object he made in France. In his early Paris days, Ray also met and fell in love with Kiki de Montparnasse (Alice Prin). Kiki was an artists’ model and became Ray’s companion and muse for most of the 1920s, starring in his experimental films and photographs. She is the model in Ray’s famous 1924 photograph Le Violon d’Ingres.

When the Second World War broke out, Ray returned to the United States and settled in Hollywood, where many expatriate artists found a new home. He spent 10 years working in Hollywood as a fashion photographer and contributed his unique vision to that field, becoming very successful. However, his heart belonged to Paris and he longed to return, so when the war ended, he moved back with his new wife, the dancer and artists’ model Juliet Brown. The last 25 years of his life were spent there creating paintings, photographs, films and sculptures. He died at the age of 86 on November 18, 1976, leaving behind a legacy of revolutionary avant-garde artworks that changed the face of photography forever.

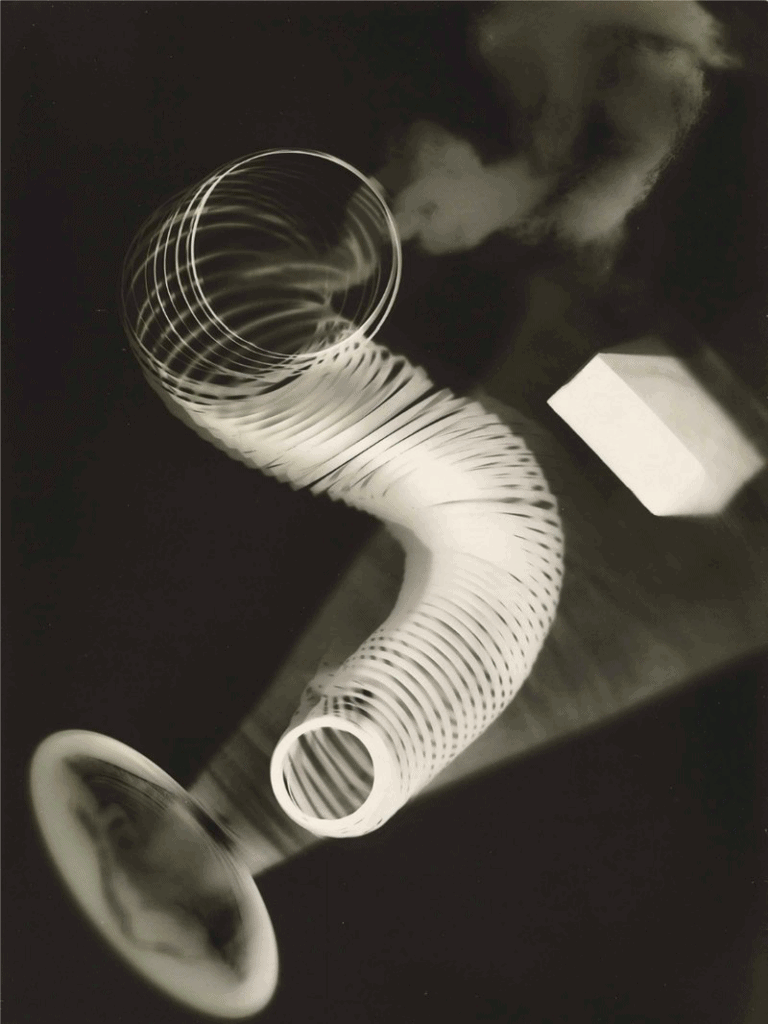

Developing Rayography

It was in 1922 that Ray made his first rayographs (a word created by combining his surname with photography). The images were photographs made without a camera, by moving objects, materials, or even body parts around on a sheet of photosensitive paper and exposing them to light and varying the angles of his light source to create a negative image. In his rayographs, Ray created surreal, irrational combinations of objects and in doing so emphasised the abstraction of images. His experiments with photography led him to the Surrealist movement, and he contributed to the three major Surrealist journals in the 1920s and 1930s.

As he became absorbed in his rayography, Ray claimed that he was leaving behind painting, stating: “I have finally freed myself from the sticky medium of paint, and am working directly with light itself.” However, he continued to paint throughout his life, using what he had learned from his experiments in photography in his paintings. Still, he rarely showed the paintings.

In 1929, Ray began a love affair and artistic collaboration with the Surrealist photographer Lee Miller. Together, they experimented with and reinvented the photographic technique of solarisation. Some of the best pictures Ray took were of Lee Miller, and when she left him in 1932, he fell into a deep despair that he expressed and processed through his art. A famous piece that he made to deal with losing her is Object to be Destroyed (1932), which is a metronome with a picture of one of Lee Miller’s eyes ticking back and forth and the instructions: “Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.”

Most famous works by Man Ray

L’Enigme d’Isidore Ducasse (The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse), 1920

Created a year before Man Ray left for France, this early ready-made shows Marcel Duchamp’s influence and assistance. In accordance with the theme of chance, important to the Dada artists, but also anticipating the Surrealists’ interest in the creative power of the unconscious, a sewing machine is wrapped in an army blanket, and tied with a string. As the viewer is encouraged to look with renewed curiosity to the object beneath and the space in which it exists, an ordinary object is given new sculptural qualities. Both the title and the imagery are inspired by the work of French poet Isidore Ducasse, but Ray never revealed the ‘enigma’ and intended the work as a riddle for the viewers to solve .

Objet à détruire (Object to be Destroyed), 1923

Consisting of a metronome with a photograph of an eye affixed to the swinging arm, Objet à détruire was first conceived as a silent and constant observer of the artist in operating in his studio. The original 1923 work, however, was transformed by the artist in 1932 following the breakup with his lover and muse Lee Miller. In the second version, Ray substituted the eye of Lee Miller and added the following instructions: “Cut out the eye from a photograph of one who has been loved but is seen no more. Attach the eye to the pendulum of a metronome and regulate the weight to suit the tempo desired. Keep going to the limit of endurance. With a hammer well-aimed, try to destroy the whole at a single blow.”

Noire et Blanche (Black and White), 1926

First published in Vogue magazine, this iconic photograph depicts Kiki de Montparnasse’s head next to an African ceremonial mask. The subjects share similitaries in shape and expression but show a sharp colour contrast, which is also referenced in the title, along with the photographic process. The picture also expresses the artist’s interest in African art.

In 2017, Noire et Blanche was purchased at Christie’s Paris for 2.6 million euros ($3,120,658), becoming the 14th most expensive photograph to ever sell at auction.

Les Larmes (Glass Tears), 1932

Resembling a film still, this cropped photograph shows Man Ray’s interest in cinematic narrative. Created around the time of his breakup with Lee Miller, the work captures a model crying round glass beads as tears to aestheticize his sentiment of distress, anger, and sadness.

Where to find Man Ray’s work?

Today, Man Ray’s revolutionary oeuvre is spread among private collections and the most prestigious cultural institutions across the globe, from the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and The Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about Art Movements and Styles Throughout History here

For more about Man Ray and Lee Miller, check out our article about artists’ muses

Visit the Man Ray Trust

You may also like:

The Fantastic Women of Surrealism

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: The International Surrealist Exhibition of 1938