I believe that I will always be in awe of the straight line, its beauty is what keeps me painting. – Carmen Herrera

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. This edition fatures Cuban-American abstract artist Carmen Herrera.

In 2016, The New York Times published an article titled ‘A 101-Year-Old Artist Finally Gets Her Due at the Whitney.’ This referred to Carmen Herrera and her large-scale retrospective ‘Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight’ (September 2016 – January 2017) at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, which focused on her period of work between 1948 – 1978. Herrera, who was born in Havana, Cuba in 1915, spent her creatively formative years in 1940s and early 1950s Paris, and then moved to New York City where she spent the rest of her life. There, she quietly but steadily built her vast body of work, establishing a cross-cultural dialogue with modernist abstraction through the decades.

Carmen Herrera in Paris – Reducing the Colour Palette

Carmen Herrera initially wanted to be an architect. She studied architecture in Havana, but due to the many revolutions in Cuba in those days the university was always closed, and she became an artist instead. She moved to New York City in 1939 with her American husband Jesse Loewenthal, where she attended classes at the Art Student League. Between 1948 and 1953, they lived in Paris, where Herrera quickly became associated with the international group of artists Salon des Réalités Nouvelles (founded by avant-garde artists such as Sonia Delauney and Jean Arp). In Paris, she was also exposed to canonical works by Malevich, Mondrian and other artists of the Suprematist movement and De Stijl for the first time. During this period, Herrera regularly exhibited work with the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles and also showed works alongside Theo van Doesburg, Max Bill and Piet Mondrian and a younger generation of Latin American artists, including members of the Venezuelan Los Disidentes, Brazilian Concretists and the Argentinian Grupo Madi. Throughout her Paris years, Herrera developed a distilled, geometric style of abstraction. At first, she reduced her colour palette to three colours for each composition; soon, three became two.

Facing New York – Sharp and Minimal, Against Abstract Expressionism

Herrera’s ascetic compositions predated Minimalism by almost a decade, yet were not at all well received upon her return to New York City in 1954, where Abstract Expressionism was still the commonly favoured style. Around the time that Herrera started creating her hard-edged canvases, moving towards sharper and more minimal work, Ellsworth Kelly was also exploring abstraction, and Frank Stella was creating his famous black paintings. Yet, being a woman and an immigrant, Herrera faced a great deal of art world discrimination. As one story goes, the art dealer Rose Fried told Herrera: ‘You can paint circles around the male artists that I have, but I’m not going to give you a show because you’re a woman.’ Despite facing such adversity, she continued to paint with great determination, only rarely exhibiting her work. In stark contrast to France, which Herrera described as an accepting heaven for her as an artist, New York was hard, and she was hardly recognised. Still, Herrera was connected in a way to the New York art scene, counting people like Barnett Newman, who was working in a similar style, and his wife Annalee as her friends. They were neighbours and used to have breakfast together every Sunday.

Blanco y Verde series (1959-1971)

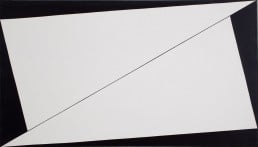

Even though Herrera barely exhibited in New York between the ‘50s and ‘70s, she produced perhaps her most important body of work in this period. Between 1959 and 1971, she worked tirelessly on her ‘Blanco y Verde’ series. These paintings consist of fields of white, punctuated with brilliant elongated triangles of emerald green. The images, which are so pure and simple at first glance, demand sustained attention from the viewer in order to unpack the layers of the image, which moves from stability to instability due to interaction of the bold colour-shapes. ‘To me, it was white, beautiful white, and then the white was shrieking for the green, and the little triangle created a force field,’ Herrera has said of the series. She has also described the colour pairing of the white and the green as similar to saying ‘yes’ and ‘no.’

‘60s and ‘70s Estructuras – Indebted to Architecture

By the mid-sixties, Herrera was creating intimate, diamond shapes on circular canvases, and by the seventies, she was producing many blunt, monumental rectilinear red shapes on fields of white. A particularly striking series consists of 7 canvases named after the days of the week, which Herrera painted between 1975 and 1978. At the Whitney retrospective, these paintings made up the finale of the show. Each of the seven canvases contains one or two large, angular black forms juxtaposed against a different colour.

The sixties and seventies also meant a return to the tenets of architecture for Herrera, one of her first loves and something that continued to influence her thinking and work. In her monochromatic series called ‘Estructuras’ (Structures), Herrera moves from drawing to painting to three-dimensional sculptural works. The three-dimensional pieces consist of two monochrome slabs that never quite fit together.

Recognition, Exhibitions, And an Insatiable Creative Force

By the 1980s and 1990s, Herrera’s artworks started to garner more attention, resulting in an exhibition at The Alternative Museum in New York in 1985, and a show in 1998 of her black and white paintings at New York’s El Museo del Barrio. Still, her first-ever sale only happened in 2004. In 2005, she exhibited at Miami Art Central and her first monographic showing in Europe was at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham, England in 2009. Big institutions like Tate Modern, MoMA, Walker Art Centre, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and Boston Museum of Fine Arts only started recognising Herrera’s work about ten years ago, when they started acquiring pieces for their collections. In 2016, the same year as the Whitney retrospective, Herrera had a major solo exhibition at the Lisson Gallery in New York — her works have been shown there seven times altogether, and her most recent Lisson exhibition was ‘Carmen Herrera — Estructuras’ in 2018.

The 2016-2017 Whitney show ‘Carmen Herrera: Lines of Sight’ was Herrera’s first New York museum exhibition in nearly two decades. Though an enormous feat for the artist who was kept in the shadows for so long, the fact that the exhibition only focused on her work between 1948 – 1978 so makes one wonder whether Herrera’s work from the second part of her life will soon receive the retrospective it deserves.

After all, at 103 years old, Carmen Herrera was nowhere near done expressing herself. She had still been drawing in her New York apartment, sketching out ideas for new paintings, and working with her assistant who helped her execute the works. Throughout it all, she knew exactly what she had been searching for with her art, and what she was trying to say through it. In her words: ‘My quest is for the simplest of pictorial resolutions.’

Latest Years and Legacy of Carmen Herrera

On February 12, 2022, abstract artist Carmen Herrera dies at age 106, having found the fame that she deserved, after decades of continuous work. Even late in life, she was greatly celebrated by museums and institutions for her beautiful compositions and a strong pursuit of her unique visual language. “I believe that I will always be in awe of the straight line, its beauty is what keeps me painting.” Being true to herself, the artist persisted in her style and signature geometrical structures of contrasting colorations until the end of her days. For the last 17 years of her life, Carmen Herrera’s endless lines were given the attention that had been owed to them. “There is nothing I love more than to make a straight line,” Herrera told the London Sunday Telegraph in 2010. “How can I explain it? It’s the beginning of all structures, really.” The Guardian London called her work the ‘discovery of the decade,’ asking, “How can we have missed these brilliant compositions?” In 2009 Herrera’s paintings were being sold from $50,000 each, and for up to $160,000 by 2014. Even though she had waited in discipline and devotion for years and years, her fame apotheosis came, as shown on the half-hour documentary, “The 100 Years Show,” by Alison Klayman about the life and work of Carmen Herrera.

Take a look at some more articles from this series and read about photographer Margaret Watkins, the pioneering abstract artist Hilma af Klint, West Coast Light Artist Mary Corse, and performance artist Carolee Schneemann.