“We declare that there has never been such a thing as a copy and recommend painting from pictures painted before the present day… We acknowledge all styles as suitable for the expression of our art, styles existing both yesterday and today.” – Mikhail Larionov on his art and the art of Natalia Goncharova

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. This week, we explore Russian interdisciplinary avant-garde artist Natalia Goncharova, who is currently the subject of a major retrospective at the Tate Modern.

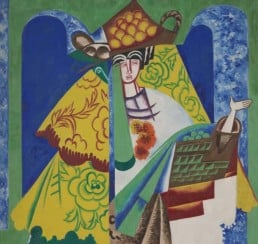

The Folkloric Avant-Garde of Natalia Goncharova

In 1913, Natalia Goncharova made waves with a one-woman show in Moscow. It was the first time any Russian modern artist received national attention. Goncharov and her lover Mikhail Larionov were leading figures of the Russian avant-garde. Yet this is not the dominant story that has been told throughout Western art history. For most people, Russian modern art immediately calls to mind the artists of Constructivism and Suprematism – Tatlin’s tower, El Lissitzky’s Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge or Malevich’s Black Square. Goncharov’s modern art was equally experimental and innovative, but had a totally different style and approach. It could be called folkloric avant-garde.

Influences from Paris

Goncharova’s generation was in touch with the latest developments in the avant-garde art scene in Paris. Many collectors of Parisian modern art before 1917 were Russian. Picasso’s embracing and deconstructing of “primitive” influences in his art made a big impact on Goncharova, who found her own inspiration closer to home. All around her, in the faces, bodies, and actions of peasants in the Russian countryside, she found this rawness, passion and primal instinct that she started translating into her art. In Peasants Picking Apples (1911), for example, the mask-like faces of the figures recall Scythian stone figures that Goncharova had seen in the South of Russia. Her nine-part series The Harvest (1911) – of which only 7 panels remain – shows a wild, passionate array of figures inspired by Orthodox icons and church frescoes. The bold orange figures call to mind Matisse’s dynamic red figures in The Dance (1910). Commissioned by Russian businessman and collector Sergei Shchukin, Goncharova would have had the chance to see this painting with her own eyes in Moscow.

Life in Paris

In 1916, Goncharova and Larionov moved to Paris themselves to experience the heart of modernism. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, they could not return to Russia and remained in Paris in exile. In Paris, Goncharova became involved with fashion houses, theatre and ballet. She started transferring her unique, bohemian folkloric style into her fashion designs for the House of Myrbor and her costume and set designs for the Ballets Russes. Working closely with important figures like Sergei Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky and Bronislava Nijinska for many years, Goncharova brought the Russian folkloric avant-garde to the rest of the world. Goncharova spent the rest of her life in France where she was a key figure of the cutting-edge art scene. She remained best known for her designs in theatre and ballet.

Everythingism

Natalia Goncharova is famous for having worked in countless different styles throughout her artistic career. Her style was so diverse that Larionov and the writer Ilia Zdanevich even coined the term vsechestvo or “Everythingism” to describe the vast range of Goncharova’s, as well as Larionov’s own, artistic output. Goncharova and Larionov had developed Rayonism together, an artistic style characterised by interacting linear forms derived from rays of light. Rayonism was also deeply influenced by the work of the Cubists in France. Yet the two artists were more interested in exploring and accepting all kinds of different styles beyond Rayonism as well.

With “Everythingism,” the artist was allowed free range in order to get their vision across. As such, one could as easily find the fractal planes of Cubism and the sharp, dynamic movements of Futurism in a Goncharova painting as a more classic Social-Realist approach drawing inspiration from the colourful rural folk culture of Russia. Some critics attacked Goncharova for eclecticism and a lack of originality. Yet Goncharova proved strong and innovative in every style that she approached. From her bold performative interventions in the streets of Moscow to the primal faces of her peasants inspired by ancient Scythian statues in Russia and her bright iconographic and folkloric figures, Goncharova’s radical spirit burns brightly. However, in the modernist period which was obsessed with strong, dominating narratives of art in which people could be easily categorised, Goncharova’s “Everythingism” was hard to place. This is one of the reasons that her notoriety faded in the post-war period, and why she has often been overlooked in the story of modern art.

“A leader of the Russian avant-garde, Natalia Goncharova blazed a trail with her experimental approach to art and design.” - Tate Modern

Natalia Goncharova's Guiding Thread

Today, a newfound appreciation for and reexamination of her entire oeuvre is underway. With her retrospective at Tate Modern running through 8 September 2019, Natalia Goncharova in all her different facets is being honoured as the exceptional artist that she was. Perhaps Goncharova would actually have fit better in the 21st century art world, where the schizophrenic fragmented condition of our contemporary world has created a breeding ground of artists working between countless different styles and disciplines. With this, a last thought comes to mind. There are many arguments to be made for the power behind an artist working in one specific, well thought through, recognisable style. With this comes authority, originality and concrete vision. Giving oneself clear parameters regarding one’s artistic style allows for an exploration that can be more in-depth, more personal, and more visionary. Still, it can be said of Goncharova that throughout her eclectic, “Everythingist” artistic practice, there was a guiding thread holding it all together: the fusion of the folklore of her Russia with the avant-garde world she lived in.