Articles and Features

Amalia Ulman And The First Work Of The Next Communication Age.

William Pym

Standards & Practices

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in his last standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

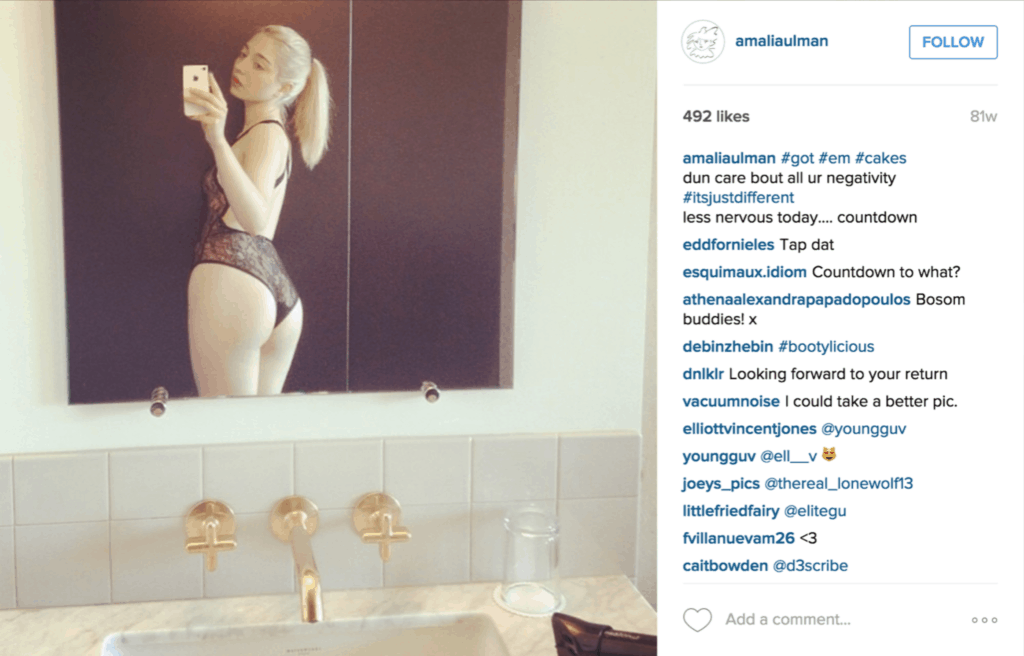

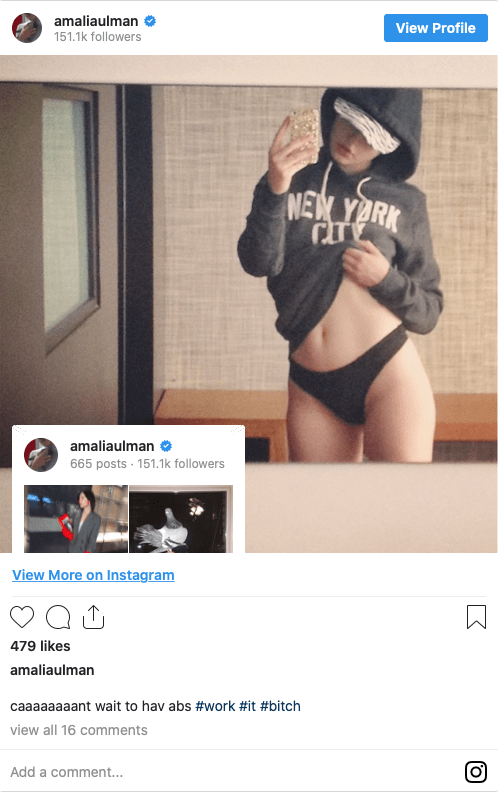

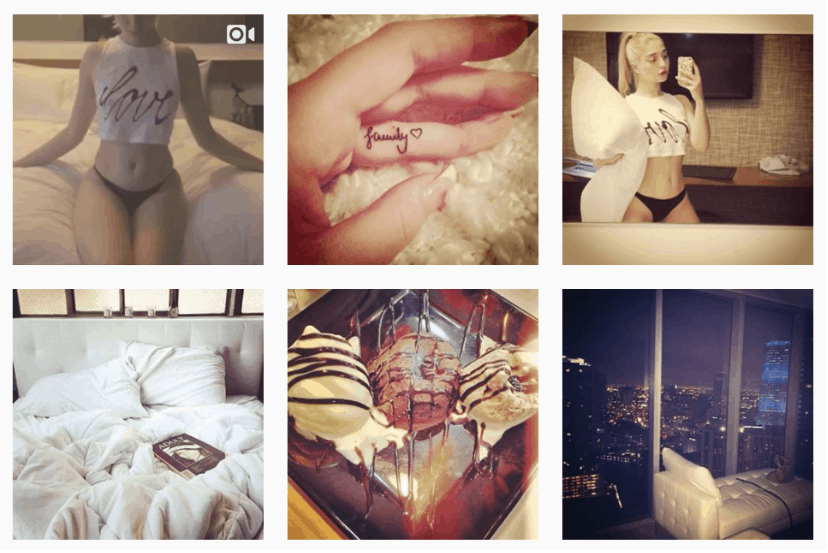

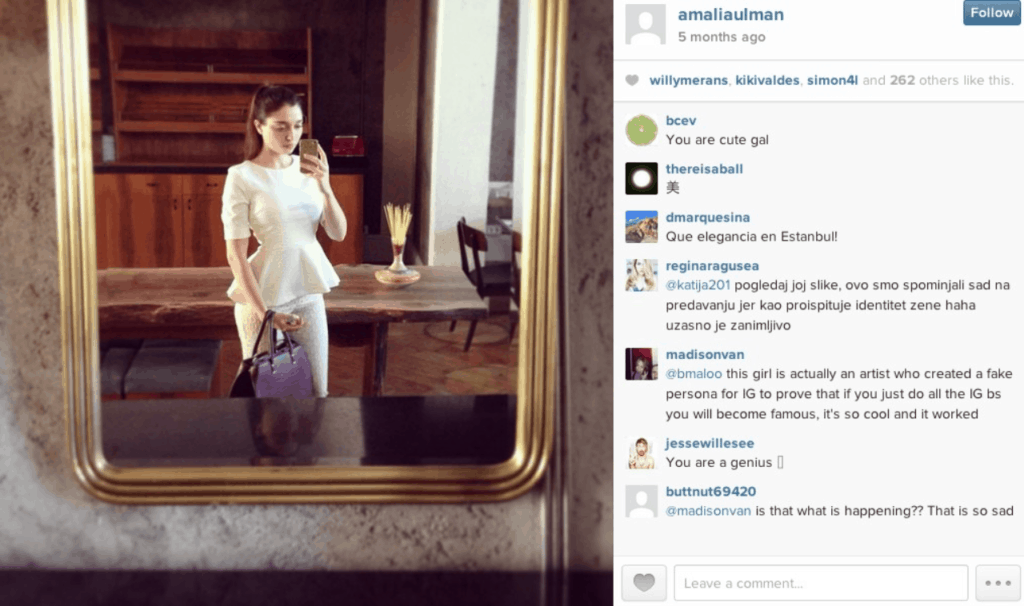

Buenos Aires-born, Los Angeles-based artist Amalia Ulman presented Excellences and Perfections as an unfolding narrative on her Instagram account over the summer months of 2014. She was 25. For this piece, which existed only online, Ulman performed a sustained exercise in character work, illusion and fantasy. She played three young women who offered themselves up for constant validation, overshared and went through drama, shared bland truisms about love and self-empowerment, and posted pictures of flowers, food and, you know, something like a turmeric latte. The drink, like everything else, was made up of a cute, dusted froth. The setting was always beautiful and beautifully lit, always the top floor, a penthouse, sipping and coy in a gilded tea room, or it was locked in the bathroom, ugly-crying about today’s indignity, or it was alone in bed, showing her butt. Ulman broadcast a tightly controlled story, chapter by chapter. The three versions of women designed by Ulman in Excellences and Perfections belong among the fragmented female archetypes of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, except now they’d come to life, rendered in flesh and set free to evolve in real time. It’s a feat of animation. Moreover, Excellences and Perfections was an interactive artwork, to which viewers could constantly respond. Tens of thousands of people were engaged live with the project at its peak, publicly voicing their feelings as Ulman flaunted the glamour of her life, looked slutty or sleepy, shared breakfast or a breakup. The audience was with her every day, waiting for her to reveal herself so they could have an opinion about it.

Excellences and Perfections is more than performance. You can tell, because there isn’t, as yet, a satisfactory and agreed-upon term for what this type of art should be called. We know about durational, total performance art — Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh’s yearlong stints staying outdoors or living in a cage in the late ’70s are their apogee — and we know through artists like Lynn Hershman Leeson that a specific brew of voyeurism, technology and womanhood got figured out as early as the ’60s. Ulman’s Excellence and Perfections is both those kinds of art. Never before, however, has art so insidiously blended with our life and rhythms. The work existed on its viewers’ phones, of course it did, but it also existed in their minds — Ulman as a sprite, hanging out in their consciousness even when they weren’t looking at the work itself. ‘Social media performance’ is, I believe, what the good people at rhizome.org called it. I can’t come up with anything better. There isn’t art language for the particular place this work exists.

Excellences and Perfections was hailed, straight away, as a significant thing, and its reputation only improves. There’s been a lot of stirring writing about the work, and every few years a new group of art people gets hip to it. Ulman herself wrote a first-person column in the FinancialTimes a few weeks ago, appearing without warning on the Thursday opinion pages, revisiting the piece and tacitly reminding us how she had foreseen the future. Technology would transform identity. In 2014, Ulman was a modern-day Cassandra; her curse was that many people would only take her butt seriously, ignoring the actual story.

Let’s consider what Ulman foresaw. At the time of Excellence and Perfections’ making, through the internet, identity was becoming more intricate and faceted than ever before, like the pointillism of Bill Evans or Cecil Taylor at the piano, ten fingers all at once playing on top of each other, making new harmonics. Identity was no longer a single melody. The globe-flattening information revolution of the internet age changed options, horizons, inflections. We could be different, and be more, because we knew more, and could see more.

“We took these personalities, these pantomimes of life, this vanity as a quirk or corollary of the internet age, until they became the defining feature of this age”

From that moment, we watched walls fall down as people became empowered through technology — through its very wires — to identify themselves, to speak out and find their history and their future. We watched new tribalism, new cliques, new forms of humans take shape. Through networks, people found their people around the world, and felt better about being themselves. And this has all been wonderful for me, somebody who was formed and saved by magazines, house shows and radio, the xerox-and-postal-service information networks of the 1990s underground. It’s easy to see this access to information and resources in a positive light. In terms of progress through shared necessary knowledge, in terms of no longer being an alienated young person, the internet is totally cool.

At the same time, all this time, we took it for sport that people could be multiple people online, that social media would become for many people their main interest, and that things would become confusing in the sea of self-promotion and profound insecurity that is social media, the world’s most popular meeting place. We took these personalities, these pantomimes of life, this vanity as a quirk or corollary of the internet age, until they became the defining feature of this age. Look around you. People who look best on screens; people who are happiest on screens; people who see screens as their friends. They’re everywhere. Old people! Kids! Everyone is into communication as cinema. “When things become images, they become fiction,” Ulman wrote in her FT opinion piece. The more we trade in images alone, untethered to facts, the less we know. Try and reach the soul of an online influencer. Good luck! For all we gained in unity and enlightenment in the internet age, we must also accept the corrosion of markers of reality, the crumble of foundations.

On balance, you may wonder, as I do, whether this is a raw deal. I definitely get blue about the vulgarity of the internet if I think about it for long enough. In Amalia Ulman, however, I’ve grown to take considerable solace, and see a way ahead. Consider Pyongyang Elegance: Notes on Communism, the diary Ulman wrote in 2018 for Affidavit, the formidable if occasionally puzzling publishing arm of the New York PR and consultancy firm Cultural Counsel. In the essay, over 23,000 words, a few hours’ reading, Ulman describes four days in the North Korean capital, a city about which she had long fantasised. She writes with absolute precision, noting each power cut, measuring the gaps between the lilies in endless lines alongside the highway from the airport, watching the sunrise. She writes in order to understand, applying Excellences and Perfections’ granular, pathological scrutiny to an actual subject, actual phenomena — people’s lives and livelihood, and the way they make her feel, expressed in plain speech. This writing lands as convincing and trustworthy, because the artist has no reason to embellish this experience. The reader feels that Ulman has been offered the opportunity to share something valuable, and she feels both lucky to have this opportunity and obliged to honour it. The reader is lucky too, because they are standing with the artist on the solid ground of experience. We are all better for sharing this terrain.

Excellences and Perfections will endure in textbooks and art-school slideshows, I’m certain, as a key artwork of the 2010s. If she continues to find worthy supporters, Ulman, who just turned 31, may share the lofty air occupied by strong, sui generis artists such as Sophie Calle and Andrea Fraser. Her 2017 exhibition at James Fuentes in New York, to which only a google search will do justice, suggested that she has blessed room to grow. I’m satisfied already, however. Amalia Ulman has taught me that if we have the intelligence and the tools to be fake, we also have the intelligence and tools to be real, and to fight for the dignity of reality in a technological age.

Relevant sources to learn more

Amalia Ulman Website

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.1 : Barry Le Va

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.2 : Kalup Linzy

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.3 : Maurizio Cattelan