Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Seydou Keïta

By Shira Wolfe

“It’s easy to take a photo, but what really made a difference was that I always knew how to find the right position, and I never was wrong. Their head slightly turned, a serious face, the position of the hands… I was capable of making someone look really good. The photos were always very good. That’s why I always say that it’s a real art.

Seydou Keïta

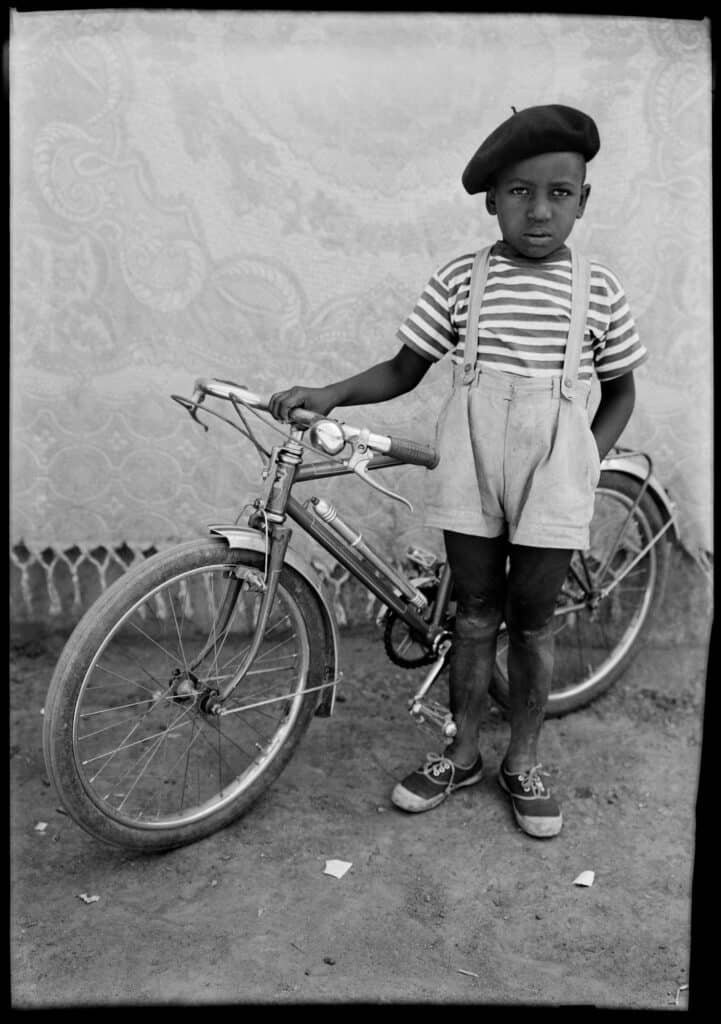

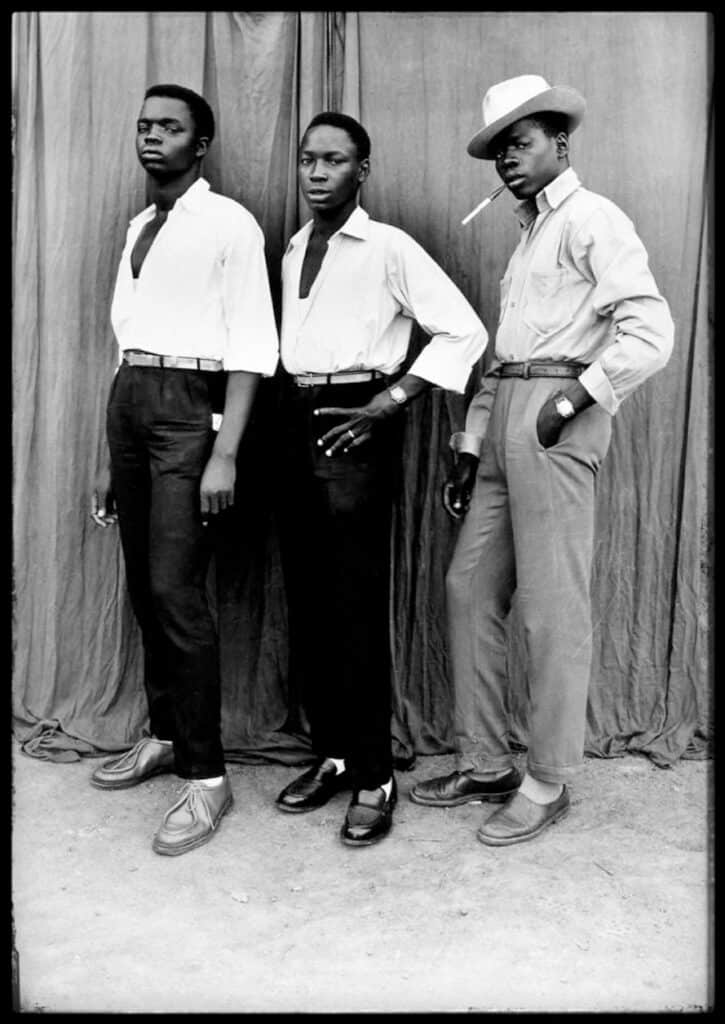

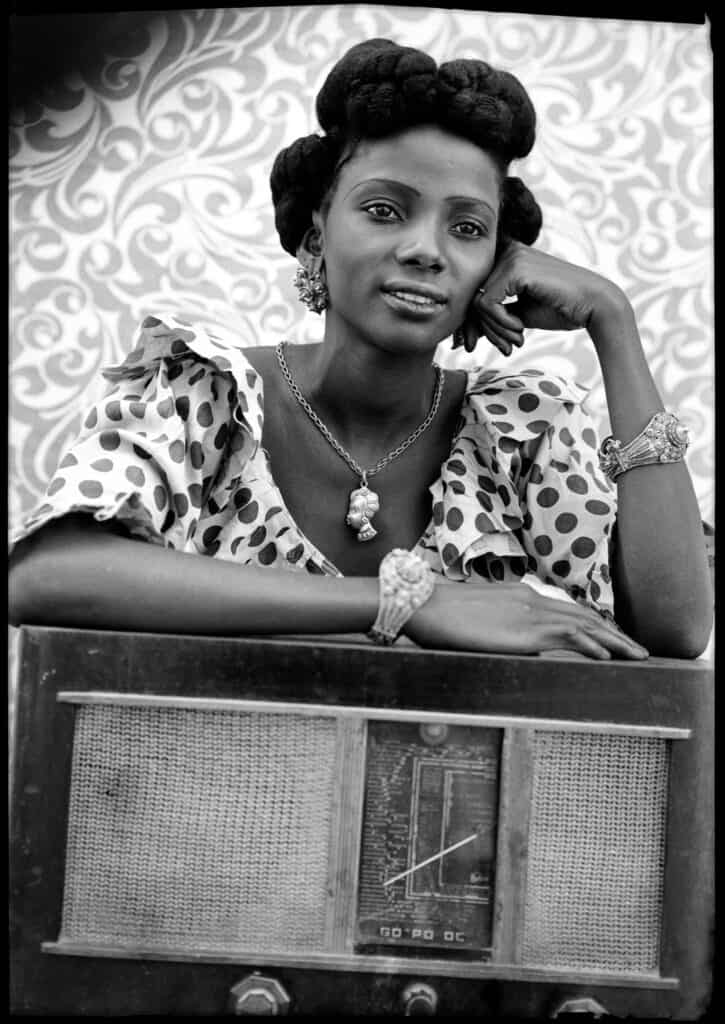

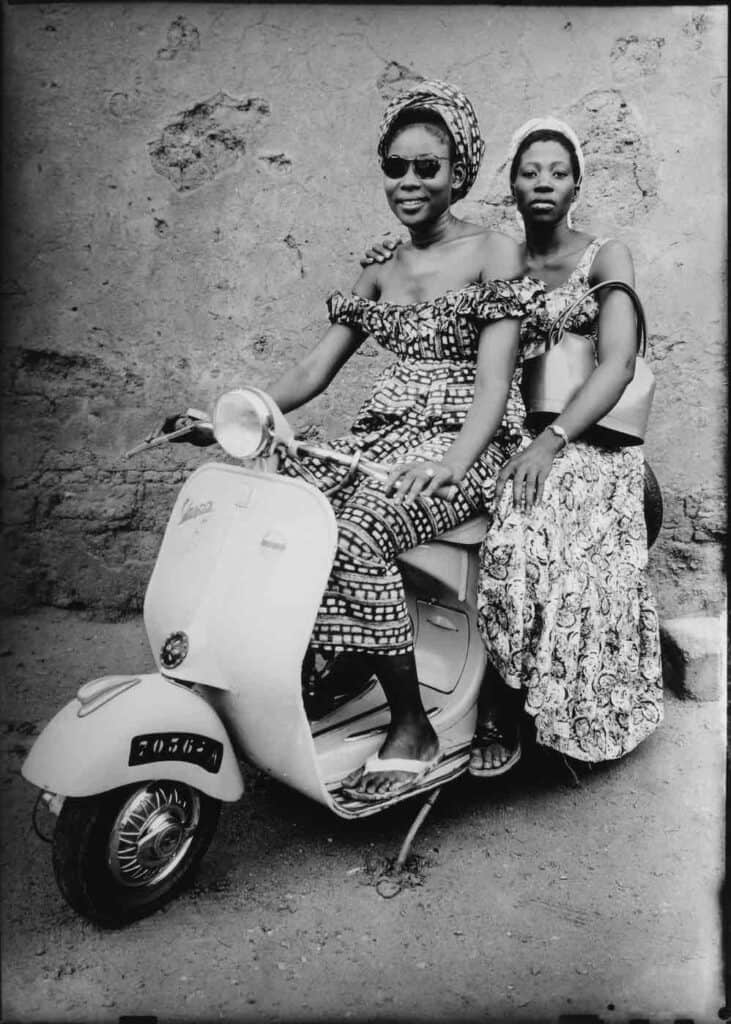

Seydou Keïta is regarded as the most famous 20th-century African studio photographer. His stunning black and white portraits of people who came to his studio in Bamako, Mali, are iconic due to Keïta’s deep understanding of the subjects’ pose. Moreover, he was a witness to the changes in urban Malian society during the process of decolonisation and gave his sitters the opportunity to shape the way they presented themselves to the world, instead of being represented through a Western gaze. Despite having built an important reputation in Mali and West Africa, he remained unknown in other parts of the world until the 1990s, when several of his photos were included in an exhibition in New York and discovered by collector of contemporary African art Jean Pigozzi and the curator of his collection, André Magnin.

Seydou Keïta Discovers Photography

Seydou Keïta was born around 1921 in Bamako, Mali, which at the time was the capital of French Sudan, one of France’s five colonies in West Africa. Instead of attending school, Keïta became an apprentice carpenter with his father and uncle at the age of seven. In 1935, one of his uncles returned from a trip to Senegal with a Kodak Brownie, a 6×9 box camera. Fascinated by the camera, Keïta started taking pictures of his family and the people in his surroundings. He was just 14 years old and remembers this as the most important moment of his life. His first films were developed at the Sudanese Photo Hall, the first camera shop and photo studio in Bamako, which had been opened by the Frenchman Pierre Garnier. Keïta began spending more and more time with Garnier in his studio, learning the tricks of the trade. From 1939, Keïta began working as a professional photographer, taking pictures on the street or at the homes of his clients. Another support early in his career came from Montage Dembele, a photographer who helped Keïta with the developing process. He was allowed to use his lab to make his prints there. Apart from the technical training he received, Keïta was totally self-taught and had no art historical knowledge at all.

Seydou Keïta’s Studio, the Most Famous Photography Studio in Bamako

In 1948, Keïta decided to open his own photo studio near the train station in Bamako-Coura, a lively neighbourhood in the Western part of the city. His former apprentice carpenters would show travellers around the station Seydou’s photographs to attract them to his studio. The demand for portraiture was on the rise and Keïta’s photo studio soon became the most famous studio in Bamako. Keïta became renowned for his talent, his eye for directing people to exactly the right pose and angle, the quality of his prints, and the freedom he gave his subjects to choose various accessories and props they wanted to be photographed with. Often, young men would dress in European-style clothing, and Keïta offered all kinds of objects for them to pose with like watches, pens, radios and scooters. In the beginning, women were mostly dressed in long flowing robes but, in the late ‘60s, they started wearing Western outfits as well.

At the height of his career, he would receive over 40 customers a day. Keïta frequently used various fabrics as backdrops for his photographs and would change these every two to three years, which allowed him to approximately date his photos later in life when he was discovered in the West – he never dated his photographs before. The interplay between the patterns of these backgrounds and the dresses worn by his clients created graphic compositions that have become some of his most popular photographs. Keïta preferred using natural light and from 1949, he used a 13×18 format view camera, taking only one picture per customer for financial reasons.

Keïta offered people a vastly different take on photography than what they had known before. When white people took their picture it was often for anthropological reasons and people were weary of being photographed for fear of being misrepresented and losing their identity. With Keïta, they could choose how to be represented by someone who shared their background. Seydou’s photographs therefore contain another important element: they portray people who feel comfortable sitting in front of the camera and are proud to show who they are and who they aspire to be. All together, they offer a portrait of Mali in full transition.

Government Photography and Retirement

In 1960, Mali gained its independence and elected Modibo Keïta as the president of the new socialist government. Due to their family ties, Keïta was recruited as an official government photographer in 1963. Keïta did not really have a choice and had to accept the position, which also meant he gave up working in his studio entirely and spent the next 14 years working for the government. He photographed formal events and worked for the security services. In 1977, Keïta retired, devoting his time from then on to his other great passion, mechanics. He spent his days fixing up cars, mopeds and photographic equipment. Little else is known about Keïta’s life during this period, but then a turn of events sparked his discovery in the West in the 1990s.

“You can’t imagine what it was like for me the first time I saw prints of my negatives in large-scale, no spots, clean and perfect. I knew then that my work was really, really good. The people in my pictures look so alive, almost as if they were standing in front of me.”

Seydou Keïta

The Global Discovery of Seydou Keïta

In May 1991, the Center for African Arts in New York put on the exhibition “Africa Explores: Twentieth Century African Arts”. The exhibition combined traditional, folk and contemporary African art, and art historian and curator Susan Vogel included seven photographs by Seydou Keïta which she had brought back from her travels in West Africa in the 1970s. The photos were credited to an “Anonymous photographer, Bamako” in the exhibition. When photographer and collector of contemporary African art Jean Pigozzi saw the photos he was blown away and asked the curator of his collection, André Magnin, to find this photographer. Magnin then travelled to Bamako and met Keïta, who showed him all his negatives, marking the beginning of a long collaboration. Magnin selected 921 of them and brought them to France, where he commenced making prints in 50×60 format. When Keïta saw these prints he was thrilled – he had never had the means to produce his photographs in large format.

In the meantime, French photographer Francoise Huguier had also met Keïta in Bamako and discovered his work. She started a project to promote African photography together with photographer Bernard Descamps, which led to the first edition of the now-famous Bamako photo festival Rencontres de la Photographie de Bamako in 1994. That same year, Magnin organised the first solo exhibition of Keïta’s 50×60 prints at the Fondation Cartier in Paris. The exhibition was a success and travelled all around the world afterwards. This exhibition led to the global discovery of Keïta’s work, eventually earning him a place among the greatest portraitists of his time.

In 1997, Magnin published the first monograph dedicated to Keïta’s work and many European galleries started showing and selling his photographs. A major exhibition was organised at Gagosian Gallery in New York City, and Keïta came over for the show, greeted by the Malian community in New York, as well as important intellectuals and artists. In 1998, Harper’s Bazaar organised a photo shoot with Keïta in Bamako. Just as in his own studio decades before, Keïta draped African fabrics in the background and carefully adjusted the poses and dresses of his models. The great photographer passed away in 2001 in Paris. A 2018 retrospective at FOAM, the Amsterdam Photography Museum, honoured Keïta’s work by showing his photographs grouped together per period.

Commenting on seeing the large prints of his negatives for the first time, Keïta once said: “You can’t imagine what it was like for me the first time I saw prints of my negatives in large-scale, no spots, clean and perfect. I knew then that my work was really, really good. The people in my pictures look so alive, almost as if they were standing in front of me.”

And, indeed, looking at a Seydou Keïta portrait is truly like meeting with the person behind the camera.

Relevant sources to learn more

Seydou Keïta official website

FOAM Photography Museum Amsterdam

The Jean Pigozzi Contemporary African Art Collection