Articles and Features

A Perfect Antidote to Disquiet Times: The Goofy Creatures of Szabolcs Bozó

By Adam Hencz

” I used to say that instead of Cubism, I represent the Cuteism movement”

Szabolcs Bozó

Szabolcs Bozó vaulted into prominence in mid-2020 when artnet news, an art magazine that rarely deals with Hungarian artists, published an article about his first solo show with Parisian gallery Semiose – an exhibition reported by Le Figaro and The Art Newspaper as well. That same year, he participated in The North Hill Residency program in California, run with support from “The Art World’s Patron Satan”, Stefan Simchowitz. But it was after the exhibition that Bozó opened at the L21 Gallery in Spain that collectors have lined up for the works of this self-taught painter. Elements such as the casual use of social media and working with great humility to the empowering nostalgia of his childish fantasy played a key role in his artistic success.

Twenty-eight-year-old Szabolcs Bozó has more than sixteen thousand Instagram followers, an absolute social media record among Hungarian artists. Before recently receiving a social media endorsement from Kenny Schachter among others, Bozó quietly had started to run his Instagram in 2018, a year after making friends and sharing a studio with fellow Hungarian painter Márton Nemes in London. Nemes became the first artist to encourage Bozó to produce more drawings, to make his ideas bigger, and to put them onto the canvas.

The Cartoonish Style of Szabolcs Bozó

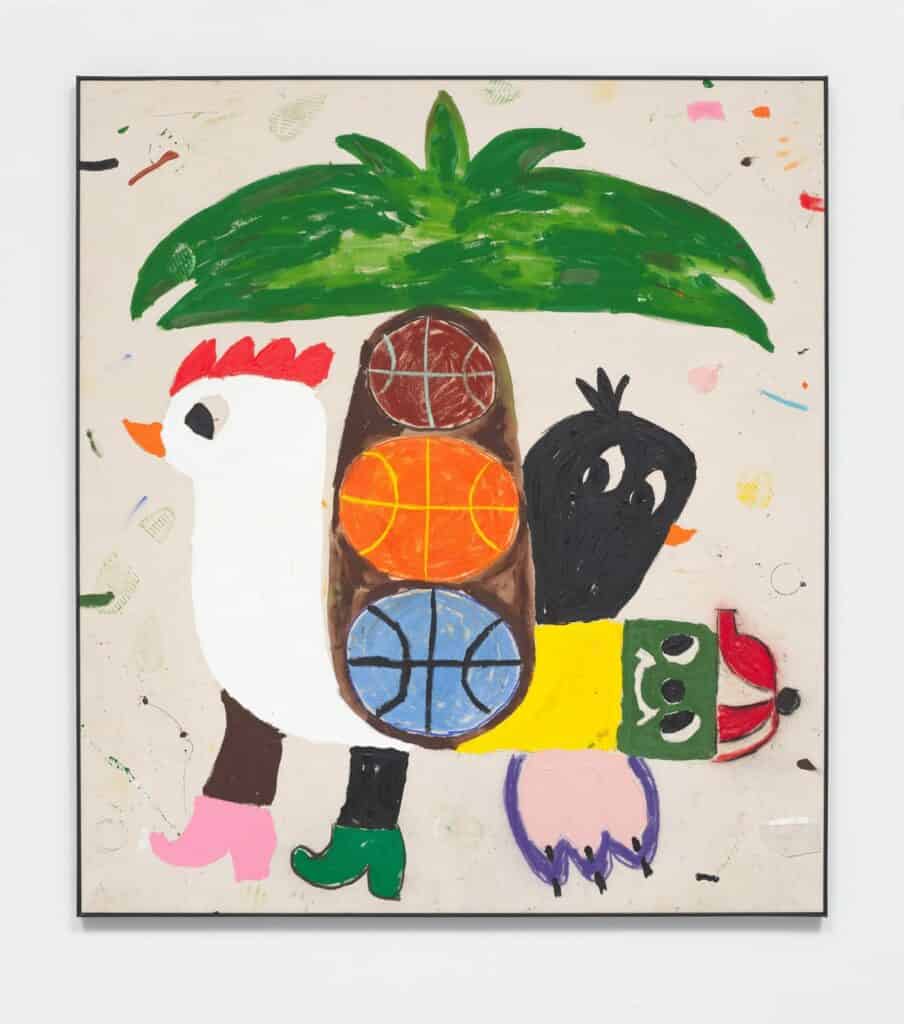

In just a few years, Bozó has forged a recognisable style for himself. His brightly coloured, zoomorphic creatures are set against a not always clear white background; energetic figures, produced in abundance and humour. Painted in large formats, his endearing characters still seem cramped in their frame, like a gallery of creatures and gull-eyed animals. “The story of what inspired me to start drawing these characters is quite banal.” Szabolcs Bozó shared in an interview with Artmagazin. “I cleaned in restaurants for years with a so-called Henry vacuum cleaner. The characteristic of this industrial machine is that two large eyes and a smiling head are printed on them. Probably it could have burned into my memory. The other cartoon-like characters are the product of my imagination, I could draw them for days. I used to say that instead of Cubism, I represent the Cuteism movement.”

In the studio, Bozó drapes his canvas on the floor, filling in his figures like characters in “a giant colouring book.” Rather than even and solid planes of pigment, he opts for a looser hand. In this way, the green skin of an elephant, or the blue flesh of an octopus, become mottled, each inch an abstract play of chance and pattern. According to one of Bozó’s partner galleries, Semiose, the artist’s singular work deliberately flirts with the margins and develops in the lineage of the CoBrA movement (Alechinsky, Appel, Jorn) for its figures, or Franz West for its spirit. Similarities of register and style can also be detected with art brut or contemporary bad painting (Joe Bradley or Spencer Sweeney).

“In fact, I never felt like I was put into the ‘Eastern European’ category as an artist.”

Szabolcs Bozó for Artmagazin

Szabolcs’s paintings were discovered on Instagram and brought to the attention of art collectors by Mallorcan gallery L21. Since then, through numerous partner galleries, his works have been featured in shows in Stockholm, Paris, Shanghai and London. Today, collectors are virtually lined up for his new works, with significant private collections and galleries competing for his newest pieces. It is relatively rare for a contemporary Hungarian artist to achieve such an explosive success, for which a key element proved to be his ability to visually articulate the sense of life that defined 2020.

“In fact, I never felt like I was put into the ‘Eastern European’ category as an artist.” reflects Bozó on his welcome to the broader art world. “It is also true that I do not deal with political issues, my figures are mostly not tied to local pictorial traditions. Of course, there are a character or two that I bring from home. For a previous show, for example, I made a Süsü, the dragon, but the Czech figure Krtek, the Mole is also a recurring character.” In another series some less-easy-to-define creatures ride in strange vehicles or dance through the canvas. A few other, slightly monochromatic large-scale paintings frame a joyfully jumbled swirl of eyeballs, noses and smiles. What more can we ask for in these times, than such imagery made of vulnerable nostalgia and simple freedom?