Articles and Features

Changing the narrative: African American artists Wangechi Mutu and Kehinde Wiley harness the rhetoric of monumental public sculpture.

Winston Churchill once said that “History is written by the victors”, even though the litany of historical tomes recounting conflict and oppression authored by the vanquished and downtrodden are actually too numerous to mention. Nonetheless, this idea does contain the generally reasonable assertion that the truth of the past is not shaped by impartial interpretative scholarship or factual understanding, but by the might of political and cultural leaders on the “winning” side of history; those who have the power to shape historical narratives through the apparatus of propaganda; through documentary and literature, public iconography, movies, and a range of other media.

Historically, public monuments have been utilised as one such tool, communicating the rhetoric of military might or political omnipotence to the masses. However, two major unveilings of contemporary art bronzes by African American artists over the past month in New York point to an appropriation and redirection of this messaging for altogether different purposes. Established art world figures Wangechi Mutu and Kehinde Wiley each seized opportunities to restate the tropes of domineering and traditionally one-sided public art to stake impassioned claims for a new place in contemporary society for the minority and the marginalised.

In September the Metropolitan Museum announced a new public commission, one that would fill the vacant architectural niches that run along the museum’s iconic Fifth Avenue facade. Designed in 1902 by Richard Morris Hunt, the niches for the Beaux Arts edifice were always intended to house free standing sculptures, yet have always lain empty. In response to the inititiative 47 year old Kenyan Wangechi Mutu created four bronze sculptures. Known individually as The Seated I, II, III, and IV, but as a group called The NewOnes, will free Us, Mutu’s sculptures engage in a critique of gender and racial politics that is sharply observed, but also cannily conversant with the art and design language of the antecedents they reimagine. Each is an impressive seven feet tall and cast in partially polished bronze, and, as with all her work, the figures are otherworldly, mannered and fantastical. The artist has taken a motif common to the history of both Western and African art and one entirely in keeping with the original purpose of the niches: the caryatid, a sculpted female figure originally intended as an architectonic device in lieu of a column, most often supporting an entablature on her head. The best-known and most-copied examples are those of the six figures of the Caryatid Porch of the Erechtheion on the Acropolis at Athens. Whatever the historical iterations of the form, the caryatid has always been confined to her role as a carrier of massive weight. For her part, Mutu stages a feminist intervention of sorts, liberating the caryatid from her traditional duties as load-bearer, doing so in the context of a neo-classical façade whose original architects sought to convey a far more conservative set of largely Imperialist values. Each sculpture is unique, with individualized hands, facial features, ornamentation, and patination, the embellishments of which take their cues from customs practiced by specific groups of high-ranking African women. The Met’s press release tell us that the horizontal and vertical coils that sheathe the figures’ bodies function as both garment and armour, and that they also reference beaded bodices and circular necklaces, while the polished discs set into different parts of the sculptures’ heads allude to lip plates. Mutu’s hybrid figures are authoritative, stately and self-possessed, but through their position on the Met’s facade they announce a new interpretation of the politics of power, culture and representation.

“They look as if they are charged with a role and responsibility. They have come to look and bear witness, and to reflect back to us what we are.”

– Wangechi Mutu

As Mutu said, “ I want these figures to appear to have come from elsewhere, from afar, recently alighted in the four niches. They look as if they are charged with a role and responsibility. They have come to look and bear witness, and to reflect back to us what we are. Amid the deep existential crisis we are immersed in, The Seated—conveying a presence that is as much celestial as it is deeply human—aim to send a signal that things can and shall be different.”

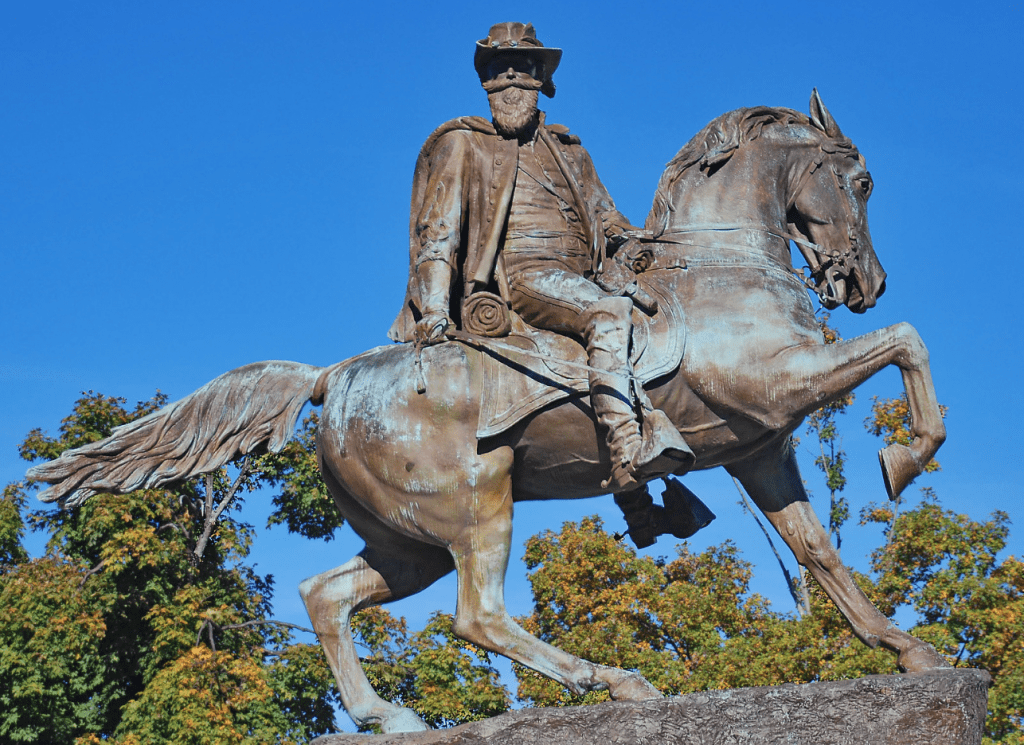

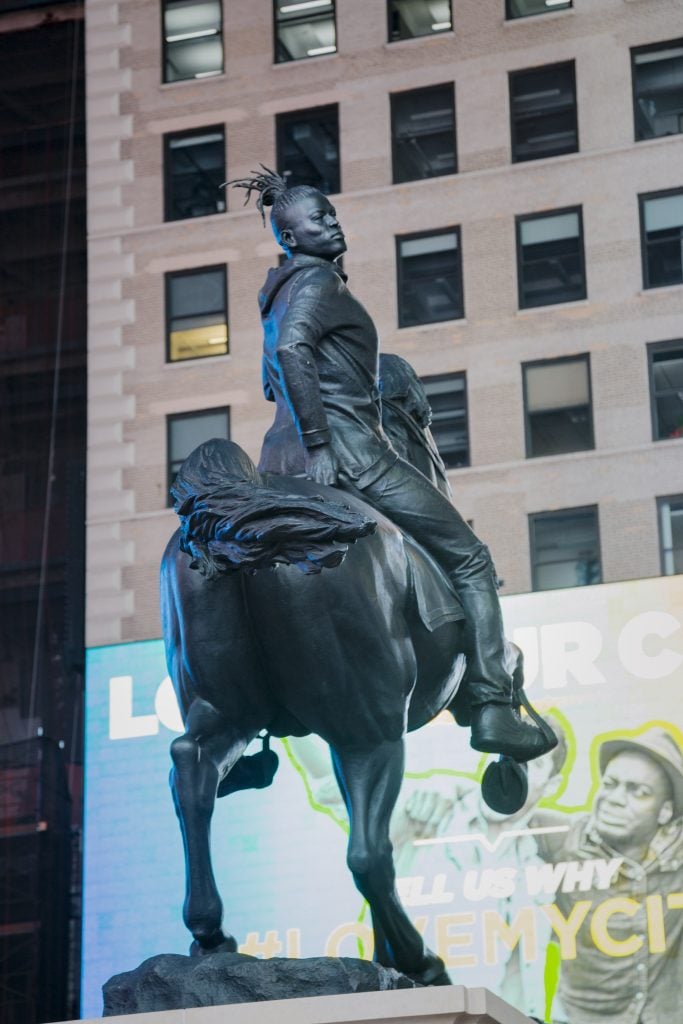

Last weekend in Times Square, also in the centre of New York City and a kilometre or two from the Met, a splendidly liveried marching band from the Malcom X Shabazz High School of Newark, New Jersey, commemorated the unveiling of a recently completed Kehinde Wiley sculpture. Called Rumors of War, the work is Wiley’s largest sculpture to date at a towering 27 feet high and 16 feet wide. Inspired by the heroic, equestrian statues of generals in Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Civil War era Confederacy that line its famous Monument Avenue, Wiley’s work shares the same bearing and posture. Of course they in turn owe a debt to this idiom in painting and sculpture that has elevated and lionised Kings and Generals since Marcus Aurelius, following a celebrated lineage through Charlemagne and including seminal works by Titian, Van Dyck, Velazquez and Rubens, amongst others. At first glance the work looks a lot like those exemplars—even the plinth’s scale and shape is copied from a Virginian, post Civil War example, but saddled atop the horse is not a Baroque potentate or Confederate general in uniform, but a young black everyman wearing Nike high-tops and a hoodie, with his braids loosely gathered in a top knot. This isn’t unfamiliar territory for the 42-year-old Los Angeles native, who has made a handsome career of adapting the language of classical portraiture to accommodate depictions of proud black men and women in aristocratic history-painting poses, including one of former President Obama that hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, but working in a different medium, on such a monumental scale, was a new challenge, “What I do in my own work here with regards to sculpture is to allow the city to be the backdrop, to allow a moving and constantly changing America to be the context in which we see this young man riding a massive horse,” said Wiley to the Associated Press at the unveiling.

In December Rumors of War will be moved to Richmond, where it will be sited near the entrance to the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, just a few blocks south of its Confederate inspiration, the monument to General J.E.B Stuart, and one of the institutions of the old South that is seeking a measure of redress through increased commissioning of works by African American artists. In the meantime, Wiley, a longtime resident of New York City whose work first gained notice at the Studio Museum in Harlem, wanted to premiere it close to home.

“Today we say yes to something that looks like us, we say yes to inclusivity, we say yes to broader notions of what it means to be an American”

– Kehinde Wiley

In front of the crowd that had gathered for the unveiling, with the work sheathed in a silver tarpaulin at his back, Wiley stood atop a speaker’s dais, and spoke with obvious emotion of his motives for making such a work. In a country and climate which has witnessed much discourse in recent years about public monuments, particularly of the South, questions abound of their continued existence. Should they, as mementoes of a shamed past, be destroyed as collective efforts embrace a fairer future for all, or is their destruction emblematic of a kind of revisionism that should be avoided, especially if we are to be reminded of mistakes of the past to avoid their repetition? That tough question posed the inspiration for both Mutu and Wiley, as it has in the works of other African American artists, especially the recent High Line plinth commission by Simone Leigh, and in the works of Titus Kaphar where this very theme is the premise for almost his entire body of work. Recalling an earlier visit to Richmond that prompted the work, Wiley recounted that, “The story starts with going to Virginia of course and seeing the monuments that line the streets. But it’s also about being in this black body. I’m a black man walking those streets, and I’m looking up at those things that give me a sense of fear and dread. What does it feel like physically to walk in that public space and to have your nation, your country state this is what we stand by? No, we want more. We demand more … and so today we say yes to something that looks like us, we say yes to inclusivity, we say yes to broader notions of what it means to be an American. We come from a beautiful, fractured and sometimes terrible past and I think the job of artists is to take all those myriad pieces, to be able to imagine them all coming back together, to be able to look at yourself, at your black body, your female body, your trans body, whoever you happen to be … to see yourself in this place that we call America.”