Art Theft: The Most Legendary Heists

Articles and Features

Stealing art for money, is stupid. Money can be made with far less risk. But stealing for love is ecstatic.

Stéphane Breitweiser

Last weekend, a high-value art theft took place at the renowned Christ Church Picture Gallery in Oxford. As cliché as it may sound, the burglars broke in on Saturday night, at about 11 pm and then made off with three Old-Master paintings: A Soldier on Horseback, painted by the Flemish artist Antoon van Dyck in 1616, Boy Drinking by Annibale Carracci (1580) and A Rocky Coast with Soldiers Studying a Plan by Salvator Rosa (late 1640s). Three paintings worth an estimated £10 million as robbery loot.

Nobody got injured during the robbery, and police say that “a thorough investigation is underway to find it and bring those responsible to justice.”

In the collective imagination, art theft is often idealised. Try to think of the stereotype of the art burglar. You are probably picturing a sophisticated tuxedo-wearing criminal mastermind; let’s say it probably does not correspond with our mental picture of a standard lawbreaker, whatever that may mean. Still, as a matter of fact, the art world is an affluent and glamorous sector and, like in any other field where large sums of money are involved, crime sneaks in, making art thieves just like any other.

For the most part, art thefts are focused specifically on financial gain, debunking the enduring myth of the erudite criminal, but still few exceptions exist.

You might have heard – it may be the exception that proves the rule – of Stéphane Breitwieser “the most consistently successful art thief.”

Between 1995 and 2001, he travelled throughout Europe working as a waiter and took the opportunity, in his off-hours, to rob almost two hundred museums—an average of one theft every fifteen days—amassing an extraordinary collection worth more than $1.4 billion.

Breitwieser is a rare case of a thief who did not act out of profit, but merely out of personal enjoyment. He only stole works considered emotionally charged to build a vast personal collection and never sold any—at least that is what he claimed when finally arrested in 2001. Unfortunately, Breitwieser had stashed all the artworks in his mother’s house and the woman, when hearing of his arrest – apparently out of spite for her son, but most likely to get rid of the evidence against him – destroyed almost the entire haul. She dumped precious artefacts into the nearby canal and cut-up sixty old masters, which she later threw out with the rubbish.

Artnapping. Stealing The Scream

In most cases, thieves may know very little about the art market, so they steal valuable artworks to make a profit. But the truth is that a well-known piece is nearly useless to its thief since hardly anyone would buy an artwork which is notoriously stolen. If a legitimate Picasso or Van Gogh might sell for gigantic prices, a stolen Picasso or Van Gogh most probably won’t. That is why more and more art criminals have no intention of reselling but burgle for ransom back to museums or art insurance companies – the so-called “artnapping”.

This was the case with the theft of The Scream by Edvard Munch (1893). On the occasion of the 1994 Olympic games, Norway’s National Museum moved the expressionist masterpiece to a new location on the ground floor gallery as part of an exhibition about Norwegian culture. On the early morning of February 12nd, the museum’s alarm went off and in less than a minute the thieves climbed a ladder, broke a window, stole the painting and ran off. They even managed to leave a note, it said “Thanks for the poor security.” However, since it was one of the most famous paintings in the world, there could be no resale market for it; in fact, one month later, the National Gallery received a ransom letter demanding $1 million for returning the painting. Through the collaboration with the British Police and a sting operation, four men were arrested and convicted; among them, their leader, the already-known art thief Pål Enger.

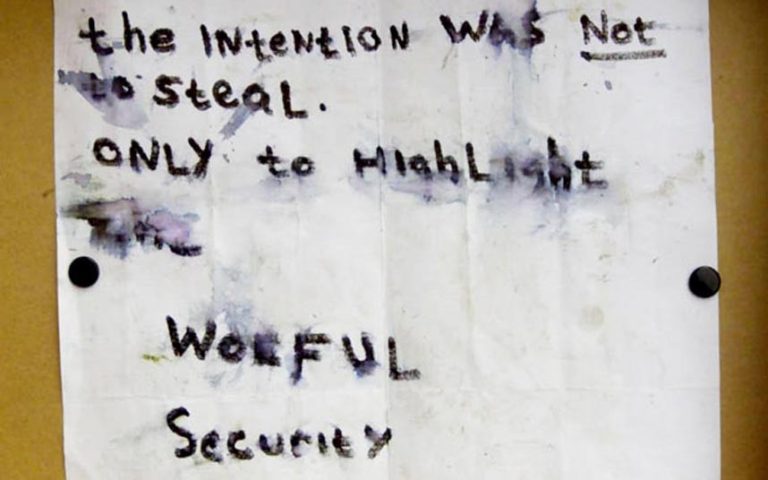

Leaving a note behind must be a particularly appealing idea for art thieves since in 2003, three days after the heist from Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester, in a nearby public restroom called the “Loo-vre”, £4 million worth of artworks by Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Gauguin were found along with a note: “The intention was not to steal. Only to highlight the woeful security.”

Back to The Scream, another version of the painting (1910) was stolen from the Munch Museum along with Munch’s Madonna in 2004. In broad daylight, two masked and armed persons entered the museum and snatched the paintings. Six men were put on trial and three of them were convicted.

After two years, the Norwegian police announced the recovery of the looted artworks with just slight damage, but the details of recovery were never disclosed.

Beyond money. Stealing the Mona Lisa

So financial gain might be the main incentive behind art theft, but it is surely not the only one. There are cases of heists due to inexplicable personal reasons, political purposes or a mix of the two. The perfect example is the notorious theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre, which brought the painting into the international limelight.

It was the morning of August 22nd, 1911, when two artists entered the museum for a study session on the Old Masters and, in astonishment, noticed that the painting was missing.

The robbery appeared so illogical – no one could sell the Mona Lisa – that people thought a stunt had taken place. The avant-garde poet Guillaume Apollinaire came under suspicion and was arrested. He, in turn, implied that perhaps his friend Pablo Picasso had something to do with the crime. Eventually, both of them were released.

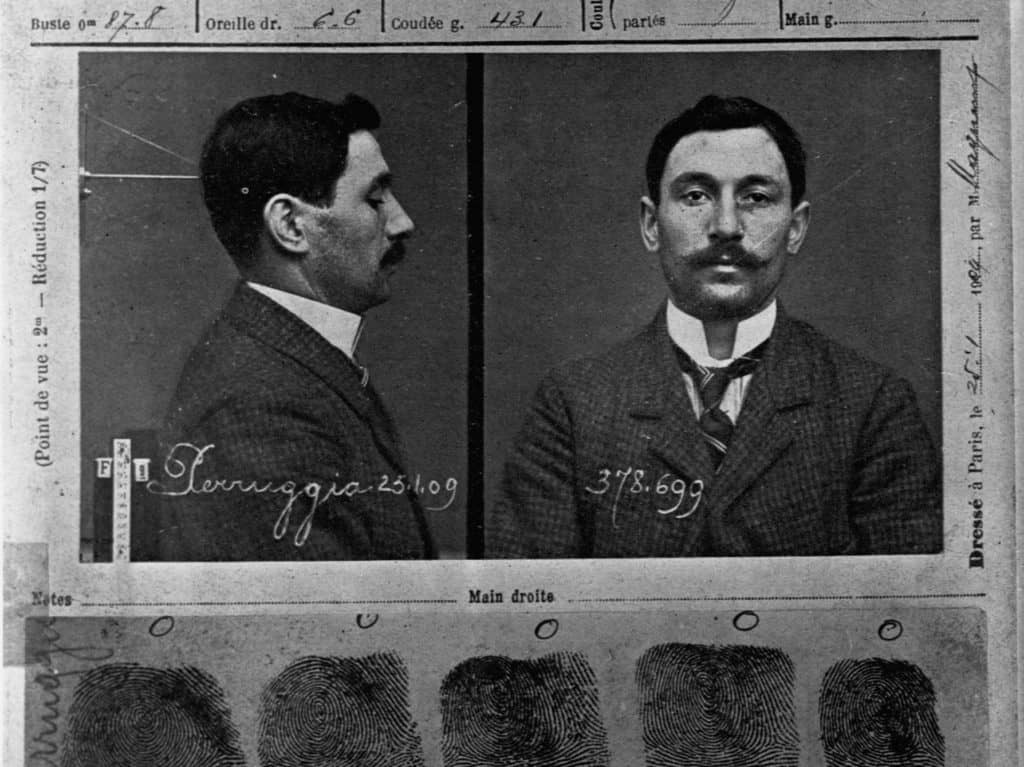

Two years later, the real thief was caught in the attempt of selling the Mona Lisa to an art gallery owner in Florence. It turned out to be the Italian Vincenzo Peruggia, who previously worked at the museum as a handyman. Peruggia claimed he wanted to return the painting to his homeland and expected a reward for his patriotism in repatriating the work.

Apparently, he had read a list of Italian paintings brought to France by Napoleon Bonaparte and, enraged, decided to return at least one of those to Italy. The Mona Lisa, because of its small size, was a perfect choice.

Ironically he picked a painting that had come to France well before Napoleon since Leonardo Da Vinci himself had brought it to France in 1517 to the court of King Francis I.

Unsolved crimes

At times, too many puzzle pieces are missing and art heists remain unsolved for decades. This is the case of the panel depicting the Just Judges, part of the massive Adoration of the Mystic Lamb by Hubert and Jan van Eyck, also known as the Ghent Altarpiece.

The entire work itself is considered the most stolen painting of all time; it has experienced thirteen almost disastrous incidents and seven thefts, going through the trials of fire, dismemberment, censorship, and war looting.

Nowadays, all parts of the altarpiece are reunited except for the panel with the Just Judges. After the theft in 1934 from the Saint Bavo Cathedral in Belgium, it was never seen in public again and the case is still open.

But the most famous example of unresolved theft is the 1990 robbery at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston. Two men disguised as police officers handcuffed and duct-taped security guards in the basement and stole thirteen artworks; extraordinary paintings as well as random low-value objects, of a total estimated value of $500 million; among them The Concert by Johannes Vermeer, but also paintings by Rembrandt, Manet, and Degas. For almost thirty years, leads continued to prove false and, to date, a gang is believed to be behind the theft (probably to use the art haul as a bargaining chip for negotiations), but the case is still open and, in 2018, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum has extended a $10 million reward for information leading to the return. If you ever happen to visit it, you will find empty frames still hanging on the walls.

Relevant sources to learn more

Christ Church Picture Gallery, Oxford

Norway’s National Museum, Oslo

Munch Museum, Oslo

Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester

Louvre Museum, Paris

Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Virtual tour of the empty frames at Gardner Museum – Google Art Project