Interviews

Artland Interviews Aurélien Le Genissel, Director of LOOP Fair

By Artland Editors

On the occasion of this year’s edition of LOOP Art Fair, we caught up with Aurélien Le Genissel, curator, writer and the Director of the fair, to talk video, film and several points in between.

Hi Aurélien, thanks for joining us today. We’re here to discuss your involvement in and views about video art, and specifically how it has led you to direct LOOP, the foremost art fair of the moving image in the world. How did you get interested in video works? And what, in your background or your professional experiences or personal experiences, caused your interest and enabled you to learn about them?

Well, in fact, I started working with video art, I imagine, in a way that a lot of people do. I have a background in philosophy, journalism, and history, but I started in the art world as a critic. In fact, I started as a movie critic. So, my background in video art is mostly, and in a weird way, through cinema, which is, I imagine, the same as a lot of people.

I love cinema and I have a lot of experience watching movies. I started doing art movie or film criticism in magazines and newspapers. After that, I switched not directly to video art but to more contemporary art generally, and focused on all kind of formats. After that, obviously, my interests and my background combined and led to my interest in video art.

How to answer whether that enables me to know more about video art or taught me more about it? I don’t know, but in a way, let’s say it doesn’t allow me to watch video art in a way that is completely non-connected with cinema.

Yes. Makes sense.

So when I watch a video art or moving image art, I always connect it with all the theory and all the background; the references that are typically associated with filmmakers involved with cinema, specially the ones that work in the margin like Chris Marker, Jean-Luc Godard or Jonas Mekas.

I think a lot of people probably do that. It’s a little bit of an inescapable parallel that’s hard to avoid, I guess you could say. But in a way that’s tricky, because you could think if someone comes from a background of cinema, he or she will be more sensitive or he would like it more or would watch video art in a way that is closer to cinema, related to narrative or with references that are closer to cinema storytelling. In fact, what happened to me is the total opposite.

The video art I like most is the video art that is clearly not in opposition, because it’s not a question of being in opposition or being not about cinema, but where the boundaries of moving image are wider than those defined by movie making. I like a lot of non-narrative video art, like Arthur Jafa or Korakrit Arunanondchai, cut-off referential video, like Ja’Tovia Gary or Camille Henrot’s work, or, big multi-screen installations that are very contemplative and more difficult to put in a movie context, like Pierre Huyghe or Anri Sala’s installations.

For me, it’s more difficult to appreciate or to be receptive to video art that is very close to cinema because I tend to think that traditional narration, with stories and Aristotelian forms, has been very well covered by cinema. But there are exceptions of course, like Clément Gogitore. The frontiers between video art and cinema are always very blurry for me. It’s not clear.

Yeah, it’s interesting, how people began to define video art and what it can encompass nowadays. It can be quite elastic. Can you recall the first video artwork that really captured your attention or captivated you in some way?

I think it was a Bruce Nauman video installation, and from watching it I was prompted to ask the question ‘what is video art?’ That’s very interesting for me, and also partially answers your previous question about how I entered video art. Anyway, it was an installation where you had a closed rectangle, a room. At the external corner of the room you have a TV screen, and there was a camera on the opposite side. The idea was that the viewer was moving, and when he or she turned the corner, walking on the exterior of the room, they would see their image on tv, and they would want to try to get to it, but as a viewer you never achieve to reach it because of being filmed from the rear and from across the other corner. I think it was called Going Around the Corner Piece; it was a very performative installation and it was one of these kind of Bruce Nauman installations about images and time from the ’70s. In the same spirit as, for example, Dan Graham’s Present Continuous Past(s) which is another installation that was very interesting for me. How Dan Graham played with the idea of time and image in a completely different way, a bigger way than cinema.

I think that’s probably a lot of people’s way into video art, as it differentiates itself from cinema, this kind of classic, highly conceptual, very philosophical, phenomenological inquiry, playing with ideas of subject and object, viewer as participant and so on. The video that you described seems to encapuslate a very classic Dan Graham way of looking at experiences and of mapping them in a sort of almost scientific way.

Yeah, yeah. I think what was interesting for me, and even now, is exactly that. It’s how video art can create displays or ways of thinking about the image and the viewer of the object that is beyond cinema, because they have other possibilities. In cinema, you cannot create this installation to take part in. What seems important for me in every format -litterature, painting, video…- is for them to use and explore the specific limits of their own language. To maybe achieve the same emotion for the viewers but using different language. To be honest also, I entered video art through a more classical way. As I said, I am a big lover of cinema. One of the greatest filmmakers for me is Jean-Luc Godard. And the last videos of Jean-Luc Godard are more and more close to video art for me—the difference is not so big. Films like Histoire(s) du Cinéma or Éloge de l’Amour cover themes that are more close to video art.

So now you’ve taken these interests and you’re organising an important fair for art of the moving image. How long have you been the director of LOOP, and how would you best describe and summarise its main mission and its objectives?

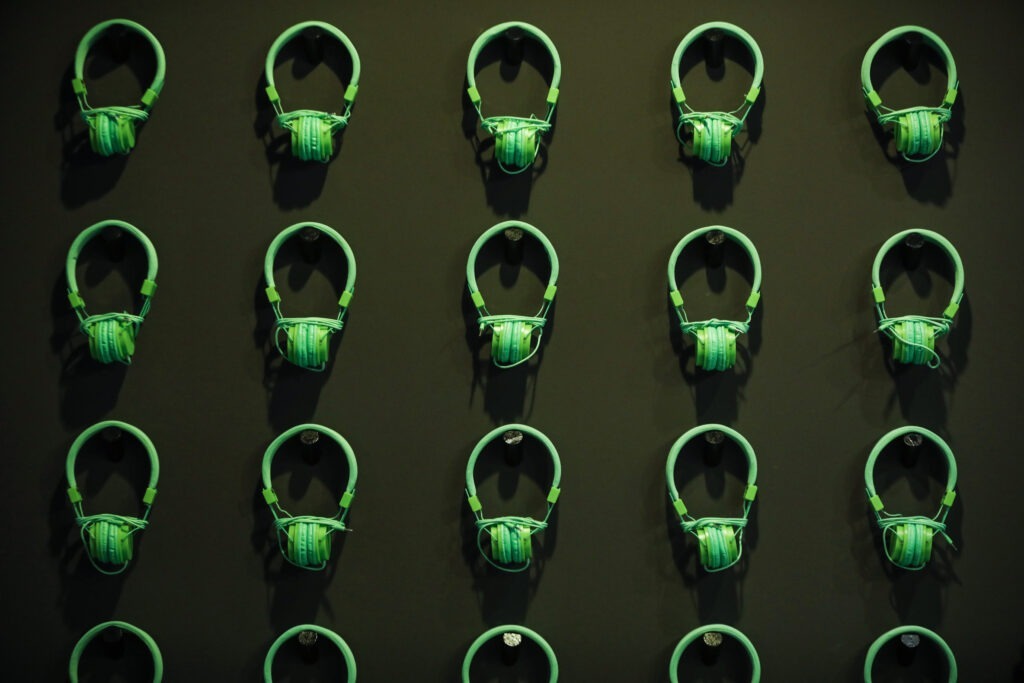

I’ve been Director of LOOP Fair for two years now. So, it’s my second year. The core mission and main point about LOOP, and a very positive aspect of it, is that we are a fair, but we have also all the things around that which we call The Festival, LOOP City Screen, and these consist of many other things that support the fair. I am the director of the fair itself, and the main core of LOOP is obviously the commercial fair. It’s about galleries supporting video art, but we have this additional way of supporting video art artists and viewers through the festival that takes place around the city (Barcelona). For the fair, the main idea and core of LOOP, which is quite easy, and in fact, for me, it works very well, is based on this simple idea that it was impossible to display video in a classical fair format, because you don’t have time and you don’t have the place to do it. Some art fairs like Art Brussels for instance are starting to create these video art environments/sections within the normal fair. So, the idea was to create this fair, and only for video works, in a hotel. Every gallery has only one video from one artist in one room. So, the viewer has the time to spend and to sit in the room and to watch video in a proper way.

Will you still be able to maintain some of the festival and city aspects due to the situation with the Corona pandemic?

Yeah. It’s not easier than the other years, and that’s why we also switch the fair a little bit—with the online offerings and an exhibition I curated in the Museu d’Història de Catalunya called Tales From an Old World. Luckily in Barcelona right now the exhibitions and the museums and the galleries are open. So, the activities of the festival and LOOP Salon are still in place and are happening right now this week. We are open!

Yes. And then the commercial component of the fair, how does that work exactly? Do galleries apply like an ordinary art fair, but according to the one gallery, one artist, one artwork idea? Do they get invited? What are the main criteria for exhibitors?

The way of participating in LOOP is by invitation, which is an invitation that can have many forms. It’s not like an exclusive club, but we like the idea of us inviting also because we are only a medium sized fair. We are not a big fair. Usually in a normal year, we present 40 galleries, more or less, which for video is quite a lot, but for a fair generally, this is not a big, big fair. So, the idea is to have an invitation. The galleries send us one video; the video they want to present. We have a committee of experts, which includes six collectors from different countries (Haro Cumbusyan, Renee Drake, Josée & Marc Gensollen, Isabelle &Jean-Marc Lemaître). Combined with the LOOP team, we have to accept the videos chosen this way. So, that’s the way it works.

So, you have a consensus or a majority decision to admit a video for inclusion?

Exactly. Yeah. We don’t indicate to them what to submit. But sometimes we help them with specific aspects like, for example, the duration of the video, the price of the video, things that they don’t think about, because for us, it’s important not to create a fair that it’s impossible to see. In my case, I cannot speak for everyone, but in my case, I do try to commit to watch (all the videos) in one afternoon, like a usual viewer of LOOP. It’s not always possible, but last year, for example, I really watched all the videos during a single afternoon. There are some videos, for example this year, that are two hours long, but these are videos that are conceptual or contemplative. You don’t have to watch it for two hours. You can get the point after five minutes.

Okay. You can get the essence of the work in less time than the entire duration?

Exactly. The idea is to be respectful with the viewer also. We try not to become the same as a big fair, because the idea was not to be or do the same, where you cannot physically see all the works presented in Art Basel. Also at Arco, even Artissima, it’s impossible to see all the artworks in these fairs. So, in this case, the idea was to be able for the viewer to have the possibility to really watch all the videos. That’s why we also present just one video from one artist per gallery.

Nice. That’s an excellent way to facilitate attention. And what key developments would you like to see in the art world generally in relation to video works? Can you explain? Amongst galleries, amongst collectors—the general consciousness about them and their place in the grand scheme of things, shall we say. You are developing a way to address this?

I’m maybe going to surprise you, but I’m not pessimistic, or that critical about the position of video art. I don’t know about the collectors, but in terms of the institutional part of museum, I think there have been a lot of efforts, and I’ve seen a lot of great video work exhibitions. I think institutions are starting to collect and to present much more video. I’m not going to enumerate all the exhibitions, but obviously in Europe, we have seen big exhibitions of Bill Viola in London, in Paris, in Barcelona, John Akomfrah, who is an artist I love, was at the Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid and has always had a lot of exhibitions, Isaac Julien too, a recent Christian Marclay’s show at MACBA Barcelona and I probably forgot some. There’s a lot of important video artists, and museums are making efforts to display these exhibitions very well. And recently you and I also talked about the exhibition Strange Days: Memories of The Future, put together by Massimiliano Gioni in London, which for me was the best selection of video art I’ve seen yet. It was in the centre of London, in a strange not exactly abandoned building, or I don’t know what, but it was simply amazing. That also speaks about the good shape of video art in a good way. So, I’m not so critical about where it can go.There’s also something that our times now will help with the context of what I call net art or Internet video, or creations through online realisation, which for me are part of the moving image. But as always in our art history, the people that are here before, the ones that arrived first, maybe snobs to the later arrivals, I don’t know if you can say that! There are a lot of very interesting artists in this field right now, like, to name some, Eva & Franco Mattes, Jon Rafman, Bunny Rogers, Signe Pierce, Ian Cheng. Institutions are understanding that: The MoMA’s Department of Media and Performance, for example, acquired Petra Cortright’s “VVEBCAM, 2007” a YouTube self-portrait via webcam of the artist. But because of existing snobbery, the new arrivals that expand the medium and other kinds of digital art are having a hard time maybe in receiving the legitimacy and recognition they deserve. I think with the pandemic and us all watching so much more video, and moving image in general, I think it will help to broaden perspectives. I think that’s the bigger challenge of video art formally.

I guess that’s true, time will tell. We’ve all got more used to our screens than ever before in pretty much every way. In that case, how would you like LOOP to grow or develop? What do you see in its future in relation to this that you’ve described?

Well, for me, and this is a personal opinion and not the institutional opinion of LOOP; I think LOOP is a big family, so internally we all have very different opinions. But for me as an art fair director and critic, one of the things I like the most and one of the challenges I like to work with is to push the boundaries of the video art definition that has been established. When I ask some galleries, when I speak with them, some of them are not very happy about putting different kinds of video art in the fair. Even the committee or the experts we talk with are sometimes reluctant, I don’t know if you can say, to integrate new ideas and things. Last year, for example, and I’m not going to give a name, sorry about that, but we had a big gallery; a very big gallery with a very, very big artist that wanted to present a kind of video, but it was a video work that had been transformed into a video game. It was very interesting. After a lot of discussion, internal discussions, and also with people who support LOOP, obviously, because we have to take into consideration everyone’s view, we decided not to present this video, just because the format wasn’t the traditional one – and, to be honest, also because the distribution was not a classical “purchase”, which is another very interesting theme about video art. In the future I want to consider more what the possibilities are, as in every aspect of society, I imagine for an artwork also. Sometimes we can be kind of conservative, and I would love to try to push the boundaries a little bit more and play a little bit with all these possibilities, because there are very good new paths out there.

Yeah. You’ll probably find in two year’s time, for instance, if the same set of circumstances were applied, that probably everyone would say, “Of course, we should include it,” because that’s just how these things go over time, right?

Yeah. If you can be one of the guys helping it and showing it for the first time, for me, it’s one of the challenges. It’s interesting for me to go and discover new ways of moving the conversation forwards.

Also, to come back to the beginning of our conversation, this is a way for me to know and to show how I entered the video art world. The art world, one of the characteristics and one of the things I like the most is that the frontiers are not clear. You can include so many things in video art that are challenging; from an installation to a movie, movie for a cinema, which is also video art in a way, to a GIF, to a website or a live performance, almost whatever. There’s so many things that are video art for me.

As the world becomes more digitized, that becomes a more elastic definition all the time. I guess the responsibility or the mission of an institution like LOOP is to be a key player in the changing nature of these kinds of definitions. So, I’m going to finish with one slightly playful question just for sport. If you’re prepared to answer, what is your favourite video work, and why? Do you have such a thing?

Well, You know what is my favourite!

Well I do. But the question isn’t just for me!

Ok, I have to try to summarize what we have talked about. I have, let’s say, two video artworks that are my favourites, and they show the two main aspects I am interested in with video art. I’m interested in a lot of things, but the first is Ragnar Kjartansson’s, The Visitors, which I think for me is probably the best, not just video artwork, but any artwork of the last 20 years. I think it’s not just me. The Guardian said the same!

Yes I know. I also saw that!

Ha! Maybe I am not very original, but I think that’s a masterpiece for a lot of reasons. First, for me as a personal opinion, one of the aspects I like about video art and art in general, and again, I’m not going to be very original, is based on Clement Greenberg’s classical definition of modernism in his essay Modernist Painting: “the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself, not in order to subvert it but in order to entrench it more firmly in its area of competence“. I think that definition, which is quite traditional, works very, very well for me to see what interests me. It’s not that general, and not always true, but it’s what interests me most in the video art I like, and the art I like in general. I like so many things in art, I like literature, I love cinema, video art, painting. For me, something that makes a work great is when it expands and deepens the possibilities of the medium, where the things that the artist does cannot be done in another medium.

The movies I like are movies that cannot be as good when they are a book, which is a big, big question of adaptation of course. The paintings I like are paintings that you cannot translate into another art medium. That’s a very important criteria for me. In the work of Ragnar Kjartansson there is this idea of recording something like life in a space, which is the main aspect of cinema recording a so-called reality, but then he tries to put the viewer inside and at the centre of this reality. There are some conditions of cinema and its possibilities, which don’t really allow you to do this. That’s the problem of the fourth wall, first addressed by Bergman, Godard and others of course, of how to include a viewer. I’m not going to cover cinema history, but when you are an artist, like Kjartansson, you can play with this and go beyond these limitations of cinema.

I think Kjartansson is recreating the space itself that he and his friends were occupying in the recording in the work. I love the idea that when you move through the work, you can be, in a way, in the same place, or hear and see the same things that someone that was occupying or moving in this house was experiencing. The idea at play in the work consists of different musicians each playing the same song, but alone in different rooms of a big house. When you move from one point to another in the installation, as in the house, you hear the guitar more or less, and then you don’t hear the sound of, I don’t know, something else like the piano or the accordion. And when you move through the space of the installation, you are also somehow in the space of where the work was recorded. I think that is very powerful, obviously. After that, there’s also the history behind the images, which are incredible. The sounds of the love song too, which is related to Kjartansson and his ex-girlfriend and his personal experience and makes it, in a way, universal. The reference to ABBA’s album…there are so many layers and interpretations! The melancholy of the images and the rythm of it all is also quite fascinating. So, that’s my favourite.

To be brief, and maybe it’s a bit easier, but my other favourite work is any video of John Akomfrah, which is always very magisterial, very big with multi-screens. Really I appreciate video art that, again, goes beyond, or works on these possibilities that the cinema doesn’t have, often having different screens, having different voices. Not in the same screen, but in a big installation of multiple screens. They don’t have to be big, but in the case of John Akomfrah, the beauty of the images are so incredible that it’s better when you see it in this format. Again, the criteria is the same, and I think it’s a very good criteria. When asked about a definition, I always like to balance between two poles, because there’s no monolithic approach. Editing and contemplation, Antonioni and Tarkovski, intellectual and realistic, David Simon and Aaron Sorkin (in TV series), abstract and figurative, Anselm Kiefer and Gideon Rubin, narrative and minimalistic, Pierre Michon and Samuel Beckett, you get the point… I like both extremes but when they try to make the best of their formal decisions.

Maybe it can be a good finish for our conversation with all the online talking! John Akomfrah or Ragnar Kjartansson video artworks or artwork in general, you cannot watch it like you watch a movie. I can watch Requiem for a Dream or Memento on my screen, on my computer. It won’t be the same as in a movie theater, but yes, I will get the idea. But you cannot get the idea of Kjartansson works or John Akomfrah works because it’s a multi-screen and highly immersive experience.

It’s been great to hear your insights Aurélien, and really exciting for us at Artland to collaborate on promoting LOOP online this year. We wish you every sucess— it’s an incredible organisation and resource for art lovers and collectors. Thanks for taking so much time to share your thoughts.