Articles & Features

Brutalist Architecture: The Defining Style of the 20th Century?

By Tori Campbell

“In order to be brutalist, a building has to meet three criteria, namely the clear exhibition of structure, the valuation of materials ‘as found’ and memorability as image.”

Reyner Banham

Introduction

Brutalist architecture, or brutalism as it is sometimes called, is an architectural style that emerged internationally in the mid-twentieth century, gaining popularity in the 1950s and continuing until the 1980s. In the post-war reconstruction period and subsequent building boom it can be said to merge some of the architectural cues of the International style, the name given to the architecture of modernism beginning with Le Corbusier; with industrial techniques and materials. Stylistically it is characterised by angular block-like forms and exposed raw materials, most often concrete, resulting in a stark appearance, especially when the surface weathers to a harsh grey. Often preferred for institutional commissions such as civic buildings, libraries and law courts, brutalism has been the source of much controversy and public unpopularity since it is often unfavourably compared with the more ornate and decorative neo-classical style that preceded it for public edifices. However, the prevalence of this new international style has lead to many cultural and architectural icons.

“Brutalism is not concerned with the material as such but rather the quality of material…the seeing of materials for what they were: the woodness of the wood; the sandiness of sand.”

Peter Smithson

Coining the term

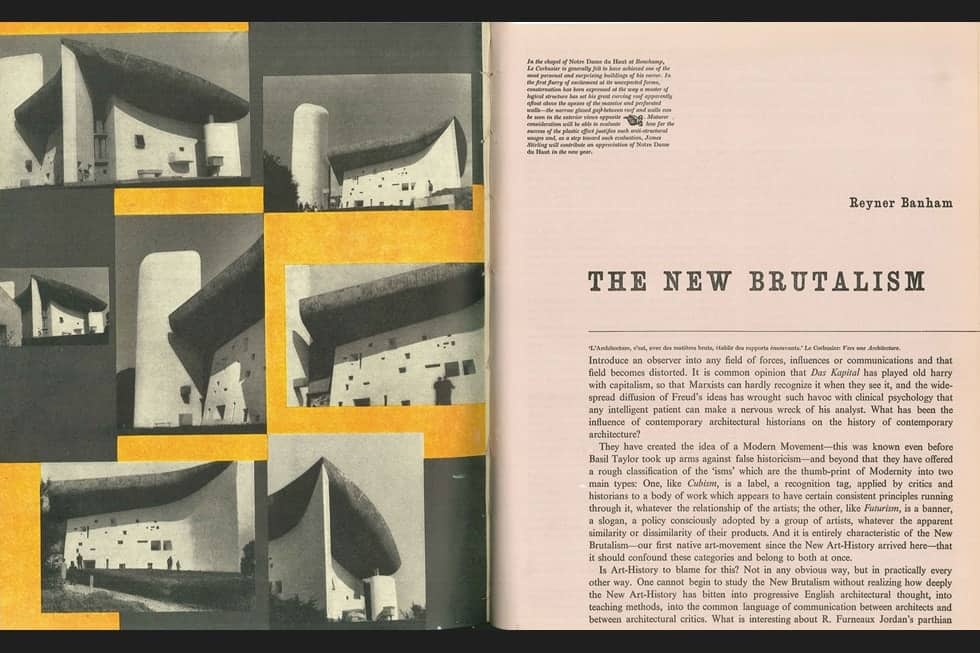

Despite popular belief, the term “brutalist” does not stem from the architecture’s aggressive geometries or repudiation of ornamentation, but is actually borne out of the description of the dominant construction material of raw concrete; or, in French, béton brut. British architectural critic Reyner Banham is thought to have coined the play on words when he published the article The New Brutalism in December 1955. His subsequent book The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic, published in 1966, only reinforced brutalist architecture’s cultural significance and turned his terminology into common parlance.

Characteristics

Brutalist architecture is most often characterised by the use of raw concrete as a predominant external building material. Modernist architects believed that buildings should be truthful, and not hide the construction of their form; thus the use of raw concrete aligned with these philosophies of honesty; displaying and celebrating the imperfections of the form used to mold the concrete. This material is in direct contrast to the past prevailing architectural style of Beaux-Arts that was full of ornamentation and lavish decoration. However, it is important to note that not all concrete buildings are brutalist, and not all brutalist buildings are concrete. Rather, it is the reverence for the materials, interest in the combination of modular and geometric elements to form a singular whole, and goal of egalitarianism that can be considered the uniting characteristics found in brutalist architecture.

History of brutalist architecture

The legendary modernist architect, painter, and theorist Le Corbusier could arguably be considered the pioneer of brutalist architecture with the unveiling of his Unité d’habitation apartments. First built in Marseille, from 1947 to 1952, he utilised raw concrete for this project as it aligned with his belief in the truth of material and the goals of modern and livable housing for all. His utopian living design was exceptionally popular in post-war Europe, and he replicated the Unité d’habitation four more times (in France and Germany); while countless other architects drew inspiration from his philosophy and form.

The brutalist architectural style truly became a worldwide phenomenon when Le Corbusier was commissioned as a master planner to design what would be a “new” city, the city of Chandigarh, India. From 1951 to 1957, Le Corbusier and his team (Maxwell Fry, Jane Drew, and Pierre Jeanneret) implemented his vision of residential, commercial, and industrial areas replete with parks and public transportation; the crowning jewels of which were the Palace of Assembly and the High Court of Justice. Brutalism soon became favoured for its emphasis on social progressivism, and due to governmental and institutional commissions around the world the architectural style became ubiquitous and exceptionally popular in nearly every geographical context.

Brutalism in popular culture

From 1971’s A Clockwork Orange to the future-thinking Blade Runner 2049, brutalism long has been the architectural backdrop of dystopian aesthetics. Often synonymous with urban decline due to the unfair stigma surrounding the council-housing residents and the stylistic shift away from the tower-housing of brutalism, the architecture became an ideal choice for directors and set designers trying to evoke the violence, anarchy, and chaos of the inner city. Additionally, perhaps due to its stark similarities to the World War II flak towers hastily constructed by Nazi Germany in Hamburg and Vienna; brutalist architecture has been put to use to symbolise the anxieties of modern life, a shockingly new yet relentlessly glum home for the menaces of society.

Brutalism’s comeback

Though no one knows exactly why, brutalist architecture is making a comeback. Over the past decade a revived appreciation for brutalism has emerged: with brutalism-focused coffee table books flying off of the shelves of design museums worldwide. Additionally, buildings that were once considered eyesores are now receiving funding for renovations and are attaining landmark-level admiration and listed status. GQ’s Brad Dunning has a simple theory for brutalism’s revival, he explains, “…maybe the movement has come roaring back into style because permanence is particularly attractive in our chaotic and crumbling world.” Whatever the reason for the style’s comeback, the worldwide prevalence of the architecture means that brutalist icons can be found globally. Here are some of our favorite:

The Barbican Estate

The Barbican Estate complex in London, England is a sprawling icon of brutalist architecture. Designed by Chamberlin, Powell, & Bon in 1954 the architects suggested a holistic approach to urban design, planning not only massive amounts of housing within the City of London but also an accompanying arts centre encompassing a theatre, concert hall, art gallery, public library, and restaurant. The massive residential estate consists of three tower blocks, thirteen terrace blocks, two mews, and multiple courts. The complex houses thousands of residents and is architecturally significant as one of London’s prime examples of brutalist architecture. As such it received Grade II listing in 2001 by Tess Blackstone, Minister for the Arts.

Geisel Library

Image courtesy of Ben Lunsford

Geisel Library, the main library for the University of California, San Diego is a distinctive brutalist work from the late 1960s dreamed up by architect William Pereira. The exterior columns are designed to look abstract hands, holding up the floors of the library as if they were a stack of books. The reinforced concrete structure creates a sculptural design at the edge of the university campus’ canyon, appearing as if it is descending into the landscape itself.

Trellick Tower

Commissioned by the London County Council following the success of his 1963 Balfron Tower, architect Ernő Goldfinger’s Trellick Tower is now a Grade II listed tower block in Kensal Town, London. Planned to provide light-filled and spacious affordable housing, Goldfinger’s creation unfortunately coincided with the decline in popularity of high-rise apartment blocks and brutalist architecture. Though the architect was an avid believer in his own work– he moved into Balfron Tower himself and took the suggestions and criticism from his neighbors in order to fine tune his Trellick Tower — the building’s aesthetic fell out of favour until the 1990s. It is now a local landmark and has been featured on film and television several times.

Boston City Hall

Best known for being universally hated, Boston City Hall is one of the most polarizing examples of brutalist architecture. Designed by Kallmann, McKinnell & Knowles, their design beat out of 255 competition entries to win the 1962 international bid for the building. Unconventional for an American governmental building, the structure was designed to express the internal functions of the building externally, through the use of cantilevered concrete forms hovering over an outsized brick plaza. With calls to demolish the building before its completion, to regular online polls revealing it as the “ugliest building in the world”, the building has been considered from the very beginning to be controversial at best. However, Boston City Hall does receive some adoration from critics, laypeople, and architects alike; and perhaps the greatest example of its polarizing popularity is that it still remains standing today.

The Breuer Building

“An inverted Babylonian ziggurat” according to one critic, the Breuer Building, former home to the Whitney Museum and current home to the MET Breuer, was designed by Bauhaus architect Marcel Breuer. Aiming to create a strong architectural statement in an affluent neighborhood characterised by New York City’s iconic limestone apartment buildings and brownstone brick row houses; the Breuer Building was once considered a somber and brutal piece of architecture. The building is now recognised as one of New York City’s most architecturally daring and innovative structures and is celebrated both as a home to art, and a work of art in itself.

HABITAT 67

HABITAT 67 is a housing complex and model community in Montreal, Canada conceived by architect Moshe Safdie. Originally Safdie’s master thesis, and then a pavilion in the Expo 67 World’s Fair, the structure is comprised of 354 identical prefabricated concrete blocks arranged to create 146 residences of various geometries. Designed to replicate the benefits of suburban homes — such as gardens, fresh air, and privacy — within a densely populated urban environment, HABITAT 67 is known for its architectural uniqueness and is considered a widely recognizable national landmark.

Slovak Radio Building

Since its completion in 1983, the Slovak Radio Building in Bratislava, Slovakia has been the focus of vitriol and criticism. Often appearing on “ugliest building in the world” lists, the structure, designed by Štefan Svetko, Štefan Ďurkovič and Barnabáš Kissling has had numerous fans in architects and architectural theorists. Shaped like an upside-down pyramid, the concept and initial designs for the Slovak Radio Building were conceived in 1967 when brutalist architecture was still in vogue, but the long building time meant that by its completion the style was out of fashion.

Southbank Centre

The Southbank Centre is an artistic complex comprised of three main performance venues along the South bank of the River Thames in London, England. In 1967-1968 the brutalist structures of the Queen Elizabeth Hall, Purcell Room, and Hayward Gallery joined the existing Royal Festival Hall. Designed by a radical group of young architects led by Norman Engleback of the London County Council, they were given a great amount of independence for their innovative project. Though they opened to plenty of criticism and outrage, the buildings are now celebrated as “an almost symphonic collaboration”, uniting an entire bank of the Thames in architectural cohesion.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more at Medium about Brutalism in dystopia

Enjoy the BBC’s article about brutalism coming back in fashion

Check out something completely different: Art Nouveau