Articles and Features

Den Frie, Artists’ Autumn Exhibition 2019

The Salon

The salon exhibition, which arrays the latest offerings from a nation’s academicians, is a cultural tradition that has endured. In Europe since the late Baroque period, and especially during the eighteenth century enlightenment era, artistic production was controlled by academies which organized official exhibitions of their members. The first Salon took place in France in 1667 under the aegis of Louis XIV who sponsored an exhibition of works by the artists of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture at the request of a delegation of its members —the name salon deriving from the fact that the exhibition was hung in the Salon d’Apollon of the Palais du Louvre in Paris, at that time the residence of the King. In the United Kingdom the first Royal Academy exhibition of contemporary art, open to all artists, opened in 1769 under the Presidency of Joshua Reynolds. 136 works of art were shown and this exhibition, now known as the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, has been staged annually to the present day.

Salon des Réfuses

For more than a hundred years the Salons were the official arbiters of emergent trends and taste in art, commented on and critiqued by the likes of Diderot, Goethe and other literary titans of the era. Participation in one, and the accompanying medal from it, was the apogee of an artist’s working life guaranteeing professional stability. Critical acclaim could ensure a stratospheric version of this success, catalysing a lifetime’s worth of lucrative patronage. Conversely, critical approbation for one’s Salon offering could cause a humiliation impossible to recover from—a career catastrophe tantamount to ruin. During the latter part of the ninenteenth century the cultural landscape began to shift away from the official forums of exhibition towards an emergent avant garde, and it was this trend that spawned perhaps the most celebrated of all alternative exhibitions, the Salon des Réfuses of 1863. The jury of the official Salon refused two thirds of the paintings presented, including works by eminent Academicians Gustave Courbet, Edouard Manet and Camille Pissarro. The rejected artists and their advocates protested volubly, complaints that would ultimately reach the ear of the Emperor Napoleon III. Whilst the Emperor’s tastes in art were traditional he was also sensitive to public opinion. His office issued a statement: “Numerous complaints have come to the Emperor on the subject of the works of art which were refused by the jury of the Exposition. His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace of Industry.” The Salon des Réfuses was thus born and proved to be a sensation. More than a thousand visitors a day attended prompting Émile Zola to report on the near riots that ensued as visitors clamoured to enter the crowded galleries where they would point and laugh at the Academy’s offcuts. In truth the attraction was more freak show spectacle than salubrious Salon (the rejects had never been displayed in this manner before)—and whilst the plan was certainly not to give a platform to left-field artistic innovations the fact remains that some of the seminal moments not only of 1863 but of all art history entered public lore in the Réfuses galleries, including Manet’s seismic Déjeuner sur l’herbe, and Whistler’s Symphony in White, No.1: The White Girl.

The anti-salon, salon.

Closer to home here in Copenhagen, Denmark’s official exhibition, Forårsudstillingen (The Spring Exhibition), has always taken place at Charlottenborg Palace, now the home of the Kunsthal. However, in spite of the country’s modest size it also boasts its very own Salon des Réfuses, the Artist’s Autumn Exhibition (Kunstnernes Efterårsudstilling, known as KE), initiated in 1900 at Den Frie Centre of Contemporary Art as a direct counterpart to its official cousin at Charlottenborg. In both instances a jury selects artists through an open call but when KE was founded the Forårsudstillingen was only open for artists with an academy education. It has always been open for everyone to apply to KE. Den Frie Centre of Contemporary Art holds a significant place in Danish art history and the current art scene. The building was originally constructed in 1898 at Vesterport by the pioneering artist, photographer, ceramicist and architect J.F. Willumsen. Willumsen is considered to be the father of the Danish art nouveau tradition. The building is owned by the artists’ association Den Frie, founded in 1891 by artists Johan Rohde, J.F. Willumsen, Vilhelm Hammershøj, the couple Harald and Agnes Slott-Møller, Christian Mourier-Petersen and Malthe Engelsted, a group collectively inspired by the Salon des Refusés and as one of their key goals had the creation of an alternative to the juried exhibition at Charlottenborg. Over the years many of Denmark’s most renowned artists have braved the submission process and entered the annals of the nation’s most renowned creative talents, including Asger Jorn, Carl Henning Pedersen, Eigil Jacobsen, Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, Svend Wiig Hansen, Albert Mertz, Per Kirkeby, Peter Land, Ursula Reuter Christiansen, Ruth Campau, Malene Landgreen, Tina Maria Nielsen – and many more.

Each year the board of KE appoints the jury. The board consists of artists who have previously had works accepted into the exhibition themselves. The jury for the 2019 edition is a cross section of some of Denmark’s most accomplished artists, including Vibeke Mejlvang (from collaborative duo Hesselholdt & Mejlvang), Peter Land, Larissa Sansour (Danish representative to the 2019 Biennale di Venezia), John Kørner and critic Maria Kjær Themsen. Artists can apply to KE as individual artists or as an artist group. The entry fee is a modest 575 DKK (approx €75/$85) and for each entry they are permitted to submit up to six art works. The artist’s name and contact info is hidden from the jury during the voting process, meaning the jurors have no clues as to the artist’s credentials or experience, and must react intuitively only on their perceptions and impressions of the works themselves. In fact the only information available to them about the individual works are basic cataloguing details such as as title, materials, size, production year and price, together with a short descriptive text, and only then if the artist chooses to provide this. The voting process consists of three rounds: two digital and one physical. In the first round the jury sits together, looks through the thousands of submitted art works (this year 546 artists submitted 2.434 art works), and if any one of the jury members vote for an artwork it continues through to the second round of voting. The second round is similar to round one—the jury together looks through the works in a digital format – but this time they confer much more with each other and three of the jury members need to agree on an art work before it passes, in best show parlance, to the final eliminator round three. The third and final round takes place at Den Frie four days prior to the exhibition opening. The artists who have made it this far deliver their works and this is the first time the jury get to experience the actual works in person. At this point a majority consensus must be achieved—if four of the five jury members agree on an art work, it is accepted into the exhibition.

Views from the Jury

We asked some of the jury members for their views on the significance of the exhibition and to describe the manner of their approach to assessing the applicants.

Larissa Sansour: “I think the most important aspect of KE is that it offers exposure to artists. It is crucial for artists with new pieces or at the start of their career to have an outlet for their work. (Selecting work) is a long process, but we mostly look for artists who are able to offer a new direction in art making, conceptually and formally. We don’t only look for new ideas, but also how well these ideas are manifested. Is the final outcome convincing and understandable? It is important for us to see that the selected artists are able to communicate their conceived ideas to an audience.”

John Kørner: “KE means a lot. Partly because of the historical significance of the exhibition and how it over time has become an institution that many people know and have a relationship with. An incredible number of artists have made their debut here over the years, so it is most definitely a love relationship. Of course, there are also many artists – such as myself – who have wanted to make a debut at KE, but instead have been denied. Despite that, I think that it is an interesting factor, because the refusal I received probably resulted in me working even harder with my artistic works. It may be a cliché, but I’m looking for originality. I am not focused on media, methods or colors, but mainly on whether the individual artist has found an interesting angle and how they have executed their idea. With a well-executed work I am not only thinking about whether the paint for example is well applied to the canvas, but it is just as much about the time spent on execution. Can you sense the time and energy that has been put into the work, and has it been done with a high level of ambition? High ambition is something that I value – one thing is to get an idea, something else is to be ambitious with that idea.”

Vibeke Mejlvang: “I like old institutions that have emerged as counterparts to the established art scene. For instance KE was formed by artists and started as an alternative to the Spring Exhibition (Forårsudstillingen) at Charlottenborg, where only academy-educated artists could apply at that time. In addition I think one of KE’s strengths is that it showcases what happens on a wide variety of platforms in the periphery of the established art scene. I look for whether the work has its own integrity, whether it can stand alone and still be interesting to the viewer. The important thing for me is that the work extends beyond itself and speaks to its surroundings. And then it is only positive if it touches me and speaks to me aesthetically.”

The artists. Our highlights.

For this year’s edition 40 artists made the cut, represented by the 103 artworks they submitted. Recently, there has been a public debate regarding gender representation in Danish institutions, precipitated largely by a research project conducted by In Other Words and published by Artnet revealing that only 2% of artworks purchased through auction houses worldwide are produced by women. Of course gender imbalance is not limited to the art world, but it is interesting to note that KE manages to entirely buck this trend, by virtue of concealing all artist information during the selection process. The exhibition this year consists 65% of works by female artists and only 35% male. 72% of the accepted artworks are produced by female artists. Here are some of our standouts from the show.

CleanTV

Surely a work that must be included for its sheer chutzpah alone. A dead or comatose dog being dragged in eternal circles by a riderless mobility scooter. What’s not to love? Puzzling, shocking and funny all at once, CleanTV (perhaps the best oxymoronic name one could also envision for the author of the work) has managed to suffuse their sculpture/installation/street theatre with just the right amount of pathos and comedy. It’s hard to know the exact message, are we supposed to speculate that the (absent) rider has befallen the same fate as the hapless pet? In the mystery lies the interest, and it probably doesn’t matter when the result is as compelling as this.

Helle Bjømebo Neidhardt

A group of photographs that show a poignant kind of absence, and the kind of silent emptiness associated with Nordic interiors since the time of Hammershoi. Beautifully lit and shot, with a chiaraoscuro that shows an almost painterly sensibility. Here is a narrative emptied of people and purpose but suffused with meaning as a result. Items are abandoned, bereaved perhaps. Time has stopped and obsolescent redundancy beckons. Achingly simple but rich in contemplative detail, this is what the memento mori looks like today.

Birgitte Boesgaard

Boesgaard presents a group of three wall mounted works that can best be described as painting or sculptural relief substitutes crafted carefully from domestic fabrics, and in a shade of white tending towards the kind of ivory only age imparts. Echoing the tropes of minimalist painting made commonplace over the past 50 years, Boesgaard’s works quietly and thoughtfully critique the machismo of painting’s recorded past with her own somewhat dainty and tactile version. Rendering Ryman’s impasto with ruched stitching, the works are no mere pastiche. With a poise, attention to detail and meticulous construction the works eschew mere ‘minimalism’, preferring instead the confidence of economy.

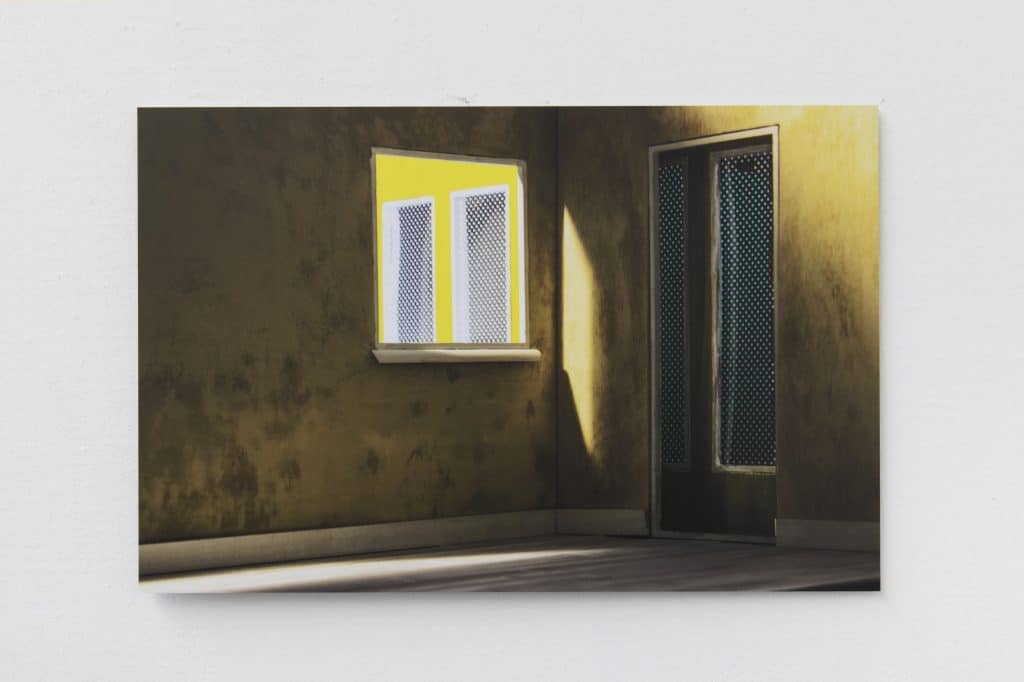

Suzanne Stokholm

A suite of 3 works, apparently of staged photography, portraying architectural interiors. The works show strange, something-other-than-real-interiors, most likely photographed after constructed models by the author. Evoking a hybridized James Casebere/Thomas Demand aesthetic, the works’ oddly dissonant colours, evidence of degradation and decay, coupled with the dramatic effects of lighting create enigmatic scenes of disquiet.

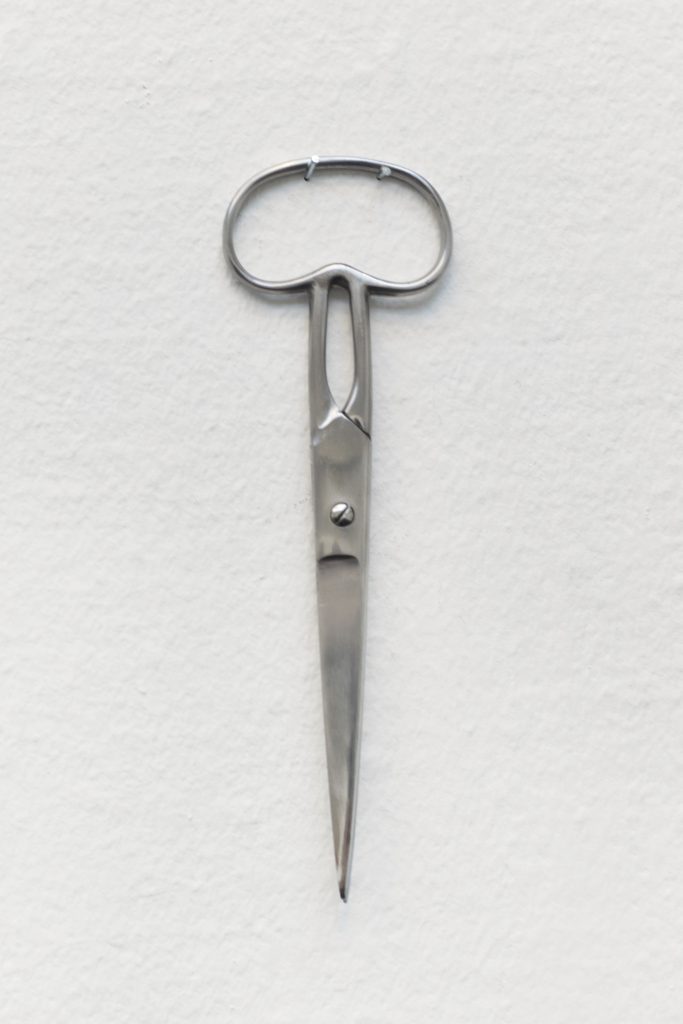

PUTPUT

PUTPUT includes 3 works in this year’s exhibition, all of which are tools modified to be stripped of their one essential function. A Scissor with one handle that can no longer open the blades to cut, a wrench bent in full circle to meet it’s other end with no possibility of engaging with a nut, a claw hammer attached to a chain instead of a rigid shaft. Redolent with the kind of mischievous humour once associated with a Duchampian artistic mindset, PUTPUT transform everyday objects into sculptural questions as to how we navigate the world. These are pop surreal interrogations of clarity.

Signe Maria Friis

Signe Maria Friis includes 3 video works. Each is a looped film interaction between two protagonists engaged in a clumsy absurdist ballet whilst covered in thick swathes of fabric. The actors strive and persevere hindered by their bulk, trapped both in the impossible claustrophobia of their stifled conditions and the futility of their impaired functionality. The heavily wrapped human forms become sculptural whilst the bundled material in turn becomes anthropomorphic.

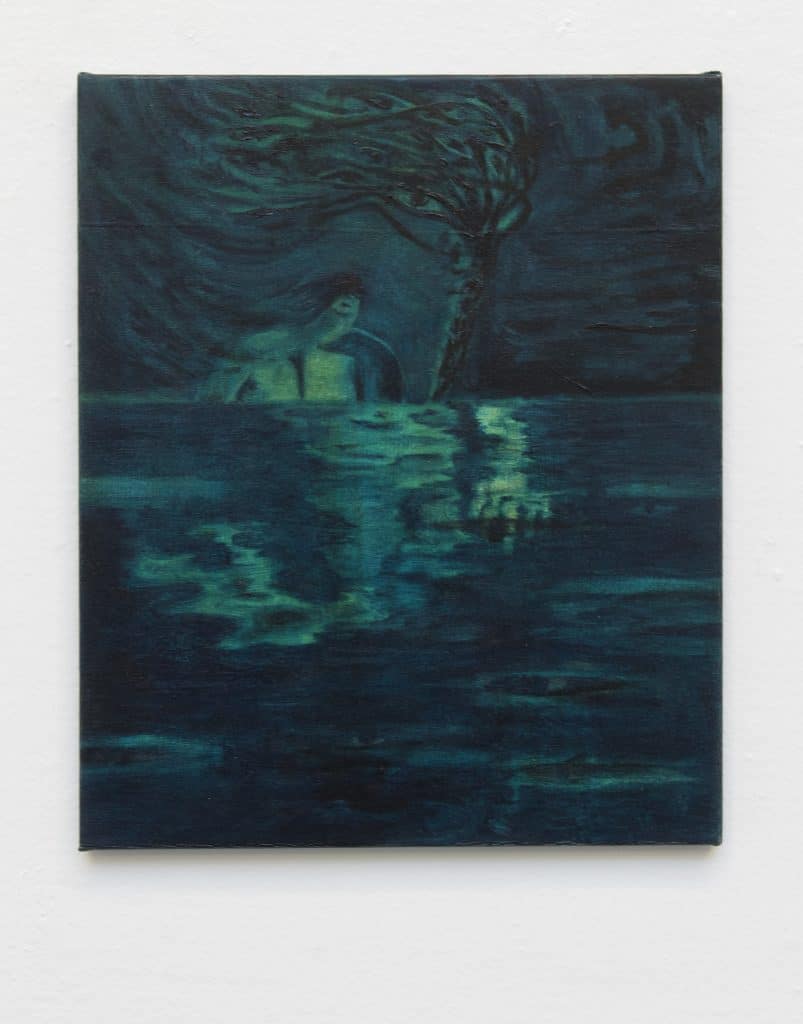

Kinga Bartis

A group of canvases essaying a dark world borne of both neo-expressionism and symbolism. Deftly and drily painted in monochromatic or highly reduced earth tones, the works depict a swampy place where all seeing eyes suffocate the pictorial space. Bartis reminds us that world will be reduced to an apocalyptic b-movie if we continue to fail to pay attention to it.

Emma Christophersen

Part performance, part painting and part installation, Christophersen constructs an apparatus for the purpose of making a painting and then utilises said equipment in a performance that demonstrates a type of painting-gesture. Her paraphernalia recalls the humble materials and vernacular of traditional domestic tools of the kitchen, scullery and garden. Donned by the artist, the mechanism enables her to perform an action painting via ink, armatures and brushes onto a canvas drop cloth positioned beneath her feet. An interesting inquiry into the meaning of ‘work’, gender roles, painting, and a new definition for ‘action painting’ almost seventy years after Rosenberg’s original.

Kirstine Fryd

A group of photographic portraits of adolescent girls at the cusp of their womanhood. Positioned quietly in indeterminate attitudes somewhere between confrontation and reticence the subjects are clothed in what appear to be old fashioned folk clothing. Not quite costume, but certainly part of the intent, the dress imbues a historic feel, reinforced by some of the compositional, pictorial and coloration elements one would associate with Flemish portraits of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Beautifully lit and crisply printed with an impeccable object quality, the works call to mind the vulnerability of Dijkstra’s portraits, but with a sensitive innocence that is entirely self-possessed.

Relevant sources to learn more

Installation art – Top 10 artists

Den Frie – Website

Den Frie – Profile on Artland