Interviews

Interview: Art Collector Nirmalya Kumar

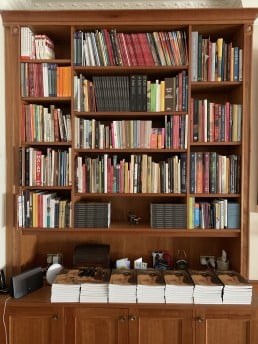

Sitting in his London flat with floor-to-ceiling paintings by Jamini Roy, Nirmalya Kumar is the picture of a passionate collector. Not only is he one of the world’s leading thinkers on strategy and marketing, but he is also a renowned collector of Indian art. He likes to say that he became a collector inadvertently, picking up his first major painting from an advertisement in an inflight magazine in 1996. Now two decades later, Kumar has become a well-known art connoisseur and owner of one of the largest collections of Jamini Roy’s works outside of India.

Nirmalya Kumar was previously a patron of the British Museum, and he has also served on the South Asian Acquisition committee for the Tate Modern. In 2013, he was recognised for his efforts on behalf of South Asian art with an Honorary Fellowship by SOAS University of London. His collection includes works by other masters such as Rabindranath Tagore and Hemen Mazumdar, but his London home houses around 60 works of art by Roy, whose work holds a special place in his heart.

Hi Nirmalya. It’s so wonderful to see you in your apartment surrounded by your paintings. Could you tell me a little about how you began collecting?

If you take artwork more broadly than painting, I have always been interested in collecting art and having beautiful things around me. The first piece that I bought was in 1988 on a trip to Bombay from the US, while I was a student at Northwestern University in Chicago. I saw this wonderful sculpture when I walked into this antique store at the back of the Taj Mahal Hotel, and I asked the store owner for some information on its history. He answered, “I can’t tell you anything about it. You want it or not?” That’s how sophisticated the guy was. Being ignorant myself, I said, “I love it, I’ll take it. Can you ship it to Chicago?” “For approximately $215 I will ship it.” Even as a student I could afford that. To this day, it graces my apartment next to the last piece in my collection, so that the first and the last piece of my thirty-year collecting journey are on top of each other.

That’s such a lovely way to arrange them. Apart from that, what are other highlights from your collection?

The first major painting I acquired was actually via a flight, maybe from Geneva to Frankfurt, where I happened to come across in an inflight magazine — you won’t believe it — a Pichhvai Indian painting. I called the gallery and asked, “Listen, how much does this painting cost?” They said “8000 Deutschmarks.” It was a very large painting, and I asked, “Can you ship it to Lausanne?” They said yes, and I said, “Is it framed?” I didn’t know anything because it was the first major painting I was buying and after they told me it was already framed, I said, “Just send it to me and I’ll pick it up.”

When the painting arrived, it was too large to go through the door, the staircase, or the elevator, as apartments are quite narrow in Lausanne. Luckily, I lived on the second floor, and my ex-wife then bent over the balcony and just pulled up the painting while the guys on the truck were handing it up for us.

That’s very funny. I guess you’re much more careful now about the dimensions of a painting. I also can’t help but notice that collection for you is almost an act of storytelling.

What I’m trying to tell you with these two stories is that every piece you acquire has a small story behind it. Part of the fun in collecting is not just in ownership but in the searching, acquiring, conserving, talking about the work as well as learning about it. For me, the enjoyment comes from the entire process of collection. It includes learning about art through research and museum visits, as well as the people that I meet through the art world. Owning the paintings is just one part of this entire journey of being a collector.

The way you talk about collection reminds me of how Walter Benjamin describes collection as bordering on the chaos of memories.

Usually I remember the story, but sometimes memory fails, especially now that I have 300 pieces. The other day my curator, the brilliant Dr. Caterina Corni, was in my Kolkata apartment and she climbs up to one of the closets and takes out two thangkas. She looks at me and says, “Nirmalya, can you tell me more about them?” And I said, “I don’t have any recollection of getting them. I don’t know what they are doing there and or where they came from.” So, we’ve taken them out and sent them for cleaning. I am generally more careful now, but in the earlier days I was less methodical.

How do you think being an academic influences the way you collect?

Because I am an academic, I am fortunate that I am not only trained to absorb what I read but also to find new directions and insights. I don’t just accept what I read, as we academics are very skeptical. In the beginning, I was just absorbing. But now, I am trying to create new knowledge on the artist by developing a unique expertise on Jamini Roy. For example, I saw a Jamini Roy up for auction in March, and by looking at the painting, I was able to discern which parts of the painting he painted and what was painted by his two assistants. Even people working at auction houses would be hard pressed to tell you that, since they deal with so many artists.

My good friend Sona Datta, who was the curator at British Museum and Peabody Essex Museum, once observed, “Nirmalya, you have just been blessed with a great eye.” When I look back on the paintings that I’ve bought, there are maybe a handful, ten or fifteen, that I wouldn’t buy again. I didn’t make a lot of mistakes in my journey and for that I am fortunate.

Listening to you talk about Jamini Roy, your appreciation and admiration for him comes across very clearly. Instead of asking you why you like his work so much, I’d like to flip the question and ask you — what do you think it says about you that you like Jamini Roy?

Firstly, instinctively, not even knowing what modern art or old art is, I think Jamini Roy is what Indian modern art should look like, and his art is the product of drinking in centuries of Indian painting and sculpture, transforming it, and then spitting out a unique language. I grew up in Kolkata and must have absorbed images by Jamini Roy all over, even though I don’t recall having heard of him. People collect something that is close to their hearts, their culture.

I find it really interesting that you collect all of Jamini Roy’s styles and periods, even the ones you like less. Why is that?

After I discovered that Jamini Roy was “the Father of Indian modern art,” it became an intellectual exercise. Although I do not like all of his styles and periods, I wanted to have the entire range of his works. Of the styles and periods I don’t like, I’ll have fewer paintings of as representatives. This allows anyone who walks into my apartment to experience the full range of his life’s work.

Does your understanding of business and finance influence the way you think about collection?

In my role as a consultant to at least fifty Fortune 500 companies in the world, I always urged them to view strategy as choice. Be clear about the destination as it helps make better choices about what to do and what not to do. Similarly, when I started collecting, I asked myself — what is my goal? At first, it was to have a full collection of Jamini Roy paintings. After I learnt about him, I realised that I can’t buy new paintings by him that will add to my existing seventy-piece collection. The way I control myself is to consult my curators when I see a new Jamini Roy. Both my curators, Dr. Caterina Corni and Dr. Suseela Yesudian, have to say that this is in the top twelve of my Jamini Roys before I will buy it. The thing is, in five years, they haven’t said yes. Of course, I buy what I like, but they are my control mechanism, so I don’t just keep buying stuff and putting it away.

I read an article once about a collector who said: “Disposal is central to good collection.” I initially thought I would never dispose of any of my collection, because I bought them with so much love. Then, I realised that his argument was sound, because when you see a better piece, you can use the resources you get from disposal to make your collection better. Suddenly, you think, why not take your 70 Jamini Roys and reduce them from 70 to 45 and then buy 5 spectacular new ones?

Apart from Jamini Roys, you also collect other artists. Could you tell us a little more about how that happened?

After learning more about Indian modern art, I realised that Jamini Roy was but one answer to Indian modern art. Yet another answer was Hemen Mazumdar, who took a Western academic style and married it with Indian images and sensibilities to create an unique language. Then there was Rabindranath Tagore who said “I’m an Indian and I’m modern and whatever I paint is Indian modern art.” He chose a very expressionist style, similar to Austro-German Expressionism from the 1920s-30s. As I learnt about Indian modern art, I learnt about these two people I didn’t collect, and what their unique answer was. I have paintings from other Indian painters in my collection, but for the most part, my London apartment is focused on on Jamini Roy, my Kolkata apartment on Rabindranath Tagore and my apartment in Singapore on Hemen Mazumdar.

Is there a reason it ended up this way?

Yes, because in India you cannot export Jamini Roy or Tagore since they are part of India’s national heritage. Since the Tagores were acquired in India, they stayed in my Kolkata apartment, and because the Jamini Roys were acquired outside of India, if I take them to India they cannot leave. I acquired my Mazumdars in India, but when I got an apartment in Singapore, the blank walls presented an opportunity. I moved the Hemen collection there because there’s no such restriction on him yet. India’s restriction is on six artists, including Jamini and Tagore, as well as anything that’s over 100 years old. Since Hemen Mazumdar started painting his major works in 1918-1920, they have just started coming under the hundred-year rule, In any case, the works of Hemen that I own are from the 1930s. But with Hemen’s work, you run into the same problem as with Jamini Roy. They both paint the same image over and over again, without dating, so it’s debatable when a painting was painted. I decided that it was a good time to move them out of India so that people can’t argue about it.

India, Singapore, and the UK make up the story of your personal life, but these places are also connected by the global story of imperialism and colonialism. Could you talk about how the global view of Indian art has changed and what you see as your role in that?

As I learnt more about Indian modern art, I learnt how radical Jamini Roy was. During colonial times, the British told Indians that India does not have any art or architecture of value. The Government School of Art was set up in Kolkata by the British with the mission of “revealing to Indians the superiority of European art.” So when Jamini absorbs Indian folk art and transforms it in the 1920s, he is saying — just like we are fighting for political independence, we are also fighting for cultural independence.

Jamini Roy defined Indian identity as distinct from what the British thought Indian identity should be, and that there is great Indian art and culture. To just say that there was no Indian art before the British came is ridiculous — we have the Taj Mahal and Chola bronze sculptures, we could go on and on. Jamini articulated that with his paintbrush, with his style and his conceptual answer to what modern Indian art is.

Are you trying to say something similar in your collection?

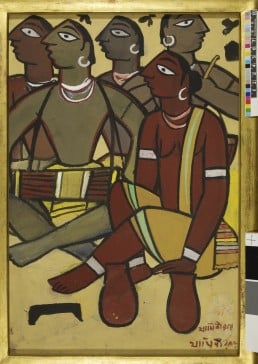

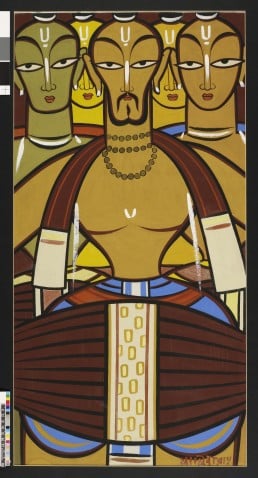

The problem with most conceptual art is that the artist can quickly become repetitive. Something I try to show in my collection is the evolution that Jamini went through as a painter, such as by displaying the same subject done three times over a period of 25 years. Here is The Musicians done by Jamini (early 1930s) which used to hang at the V&A. Still somewhat derivative, very folk artish. Now comes the 1940s, same painting, but it has now become distinctively modern art. In his final iteration from the late 1950s-60s, you can see how borrowing is not the same thing as copying. He is getting further and further away from the source, articulating a uniquely Jamini vision. Picasso was inspired by African art and Jamini was inspired by Indian folk art, but no one can say what Picasso produced was African art any more than can they say what Jamini produced was Indian folk art. He has now transcended being an Indian artist to becoming a global artist, something that he reinforces through his Christianity phase paintings.

Out of curiosity, do you ever worry about being pigeonholed as a collector?

I only collect the Bengal school from 1900-1950, which was the emergence of modern Indian art. This doesn’t mean that once in a while I don’t buy something else. My most recent acquisition is a Turner I saw in an auction catalog, which was a painting of India. Turner only did five paintings of India during his lifetime and he never visited, which is why the colours look more like Egypt than India, even though he is the greatest colourist and painter of sky of all time. This painting is one of four paintings that he did for a patron at the start of the 1800s. One is with me, one is at the Tate Britain, one is at the Clark Institute in Williamstown, and the last one is in another private collection. To get a chance to buy a painting like this with that kind of history was a unique opportunity for an Indian.

When I was twenty-three, I told my dad I needed a one-way ticket to the U.S. and 400 dollars. He said, “I can give you the 400 dollars but don’t ask me for the ticket. I can’t afford that.” In the end, he borrowed money to buy me that ticket which I eventually repaid. The Turner acquisition was to mark my return to India after 25 years of living abroad to accept a job with the Tata group.

What do you hope will happen with your collection in the future?

Up until three years ago, I never thought about it. I know I won’t give it to a museum. After talking to museums, I was told that 98% of their collections are in storage, and that if I give them my collection it will go straight into storage. Why would I give away my collection to be put into storage? I want people to see and learn from it.

Apart from that, after I’m gone, I really don’t care.

That was not the answer I was expecting.

Once I’m dead, I’m dead. I’m not possessive. I don’t want to make a private museum. Some of my friends have done so and they don’t have any visitors. They have more staff than they have visitors. More people come to my apartment to see the paintings than they do to these private museums. I don’t want any mausoleums. I’m a custodian of this collection; if they go to someone else who loves them or if they’re scattered around the world that’s up to them.

To learn more about Indian modern art, click here to download Hemen Mazumdar: The Last Romantic (2019), edited by Caterina Corni and Nirmalya Kumar.