"I like difficult paintings that people don’t want to restore. I like a challenge."

The goal of an art conservator is to maintain works of art in a state that is as close as possible to the artist’s original intention. Yet when it comes to modern and contemporary art, artists often used unusual materials and did not always consider the notion of longevity in their artistic practice. Conservation and restoration of modern and contemporary art has therefore developed into a particular specialty within the larger field of art conservation and restoration. We had the opportunity to speak with Suyeon Kim of Fine Art Conservation Group in New York, an expert in modern and contemporary art conservation and restoration, about the ins and outs of her work.

Shira Wolfe – How long you have you been an art conservator?

Suyeon Kim – A long time! Since 1994 when I graduated, and I opened my studio in 2000.

SW – That’s in Chelsea, right?

SK – Correct, in Chelsea, New York City.

SW – How did you get into conservation and restoration, and what is your particular area of expertise?

SK – I was born in South Korea, and we didn’t have proper Western art conservators. Our main traditional medium is mulberry tissue paper, which most people call Japanese paper, but it’s not Japanese paper! It’s called mulberry tissue paper and it’s this very thin paper. We therefore have a tradition of conservation and restoration of mulberry tissue paper, but no Western material tradition. This was basically introduced right after the war, so that’s a very short period for us. When I started studying, there were just two other Korean conservators who specialised in Western art. So we were only three people there back then. Now there are obviously a lot more.

My professors suggested that I study conservation when I finished fine art school – I was also doing a master of oil painting in fine art. I studied in Florence, Italy from ‘92 to ’94. I actually specialised in conservation and restoration of oil paintings and panel paintings, because in Europe there were many wooden panel paintings in the 13th century, before canvas was introduced. I did internships in Bologna, Milan, and Florence, and then I came to the US in 1999 for post-war and contemporary art.

In Europe I worked mainly on the Old Masters, because they are known for all these traditional materials. But I was very interested in post-war and contemporary art, where the materials are very different. These artists use all sorts of different materials, so I wanted to study how those react in that mixture. Because basically these artists are doing anything they want, they aren’t really thinking about the longevity of the artworks, and I was very interested in this.

"In terms of the Old Masters, we pretty much know what kind of materials they used. With contemporary art, you really don’t know. If you work on one specific artist, you have a good idea of what the issue can be, but otherwise each painting comes in as unknown territory."

SW – It’s interesting what you were saying about the longevity of the artworks. A lot of twentieth century artists did not think too much about the archival longevity of their materials, and often improvised with their media. What are some of the strangest materials you have encountered?

SK – All kinds of materials. Anything and everything! Sand, glass, human hair… I guess human hair was the weirdest thing, but that really wasn’t much of a restoration job. It was a little bit messy, we just had to comb the hair, and dust it out a little bit.

Otherwise some artists mixed paint with acrylics but then didn’t like the acrylics so they put oil paint on top. But the two are not compatible, so later on the layers detach. Those types of things need to be avoided, but at the moment of their creativity artists don’t think about the fact that it needs to last forever. They do what they need to do and at the end of the day we need to preserve it.

Some artists come and ask me: “What materials should I use?” But then they’re overthinking it, instead of thinking about their creation. So I don’t like to tell them too much what to do. I just tell them, “Do whatever you need to do, and we’ll sort it out.” But I do always tell artists, if they’re doing traditional painting on canvas, to get a good stretcher and good canvas. Especially if they’re working with a lot of medium, if it gets very heavy, you need to have a good structure.

SW – Could you explain the precise difference between conservation and restoration?

SK – We’re called art conservators, we don’t tend to be called restorers. Restoring traditionally refers to doing something more. Let’s take conservation: if you have a painting with a tear and a hole, and you are only going to repair it structurally, but you don’t want to do any colour compensation, that would be called conservation. But if you start adding some inpainting you would call it restoration. We tend to use both words because we don’t want people to think that an artwork is overly restored. Often, when people think of art restoration, they think the art is overly restored. This has happened in the past, that there was a tiny little loss and art conservators, instead of just fixing the tiny loss with inpainting, used a bigger brush and painted on the original as well. We call this: “Small brush, small money; big brush, big money.” Meaning that if you use a bigger brush, you’re finished so much faster, even though the result is not so good. We only do the inpainting and the match-to-colour when there is an actual loss on the painting. We only do it when it’s absolutely necessary.

SW – What would you say are the main differences between modern and contemporary art conservation and restoration versus conservation and restoration of art from previous centuries?

SK – In terms of the Old Masters, we pretty much know what kind of materials they used. Basically they always put varnish on at the end. And in the past people cleaned the varnish, revarnished, then cleaned the varnish again, etc. In that process some of the pigment may have been lost, but in terms of material usage it’s very similar. They ground the pigment, then mixed it with the varnish. You pretty much know what it is even though it’s not always easy since heavy inpainting can be involved. And once you take away all this inpainting, sometimes there’s nothing left. Because in the past a painting may have been overcleaned, so after taking off the old restoration campaign, you only see the really abraded surface and you could end up having to do inpainting again.

With contemporary art, you really don’t know. Most materials are commercially made, they’re not very durable, they’re not great with light, and they tend to discolour. If artists are trying to mix them or use a cheap canvas or stretcher these tend to crack. Basically canvas tension changes due to temperature fluctuation. If you work on one specific artist, you have a good idea of what the issue can be, but otherwise each painting comes in as unknown territory. We do work on lots of estates, so some artists we know very well.

SW – How would you say conservation and restoration are currently understood in the art world?

SK – Some artworks, you have to restore. Let’s say with contemporary art, the price is so high these days. So if there’s a little hole or dirt and grime, you have to do the conservation (meaning the surface cleaning, repairs, etc.) or buyers won’t buy the artwork if they’re paying such high prices. Buyers don’t want to see any imperfections. So it’s widely understood that to do conservation is necessary. With a tear, the painting is valueless. People often say: “But if you restore the painting the value will go down.” But I would always answer: “There’s no value now. You’re not going to sell anything at this point.” So if you conserve or restore there might be a small loss factor, but at least you can sell it. So people view conservation and restoration as a necessary thing to do. For example with a tear, dirt and grime, eventually you have to deal with it because it could cause further damage later on.

SW – Have a lot of things changed since you started working in this field?

SK – I think regarding contemporary art, the prices really got out of control. Some artworks became so expensive. We mainly work with wealthy art collectors and dealers and sometimes I feel like I’m a surgeon saving people, like everything is urgent. The price is just out of control and people don’t want to see even a little bit of imperfection, even though sometimes it’s totally fine. People are worried about the resale value as well.

SW – What excites you the most about contemporary art conservation and restoration?

SK – I like difficult paintings that people don’t want to restore. I like a challenge. If I get a job like that I feel sorry for the client but at the same time I get excited. It’s very rare that things cannot be done. 99.9 % of the time things can be restored. I’m trying to eliminate that 0.1 %. Especially in contemporary art, this really excites me.

SW – Is there such a thing as an average time for restoring an artwork?

SK – It’s very hard to say. We keep artworks for months and months here. Probably three weeks is the average, but it could take longer. We worked on one painting for four months, while another one could take just a few days.

SW – What was the most challenging project you ever worked on? Is there a particularly interesting case study you can share with us?

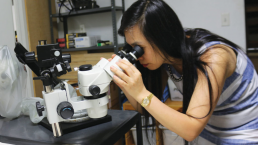

SK – We worked on a painting with at least 20 inches of tear, and then we actually weaved from the back. So we did a local repair by reweaving the canvas thread. It was very difficult work with a microscope. On top of that the inpainting was not easy since the colour was fluorescent and it was very difficult to match. It was very challenging because the tear was way too big. We didn’t want to line the canvas because the value would go down. We wanted to do the local repair but if you place a local patch then the patch will be visible later on. So it took us a long time since we were using the microscope. When you work with the microscope you feel like you’ve worked a lot after eight hours, but then you realise you really didn’t get a lot done.

For another project, we had to separate the painting from the board. The board was mouldy, so we had to shave it off from the back. You can’t just take the canvas off from the front. So it took a long time to get to the canvas area, and we had to carefully remove it all. In general it’s extremely time-consuming work. You need to have skill, concentration, time and money.

SW – What are your favourite tools to work with?

SK – The brush. We work with a scalpel, a spatula, we have a hot air gun, a small vacuum, a tiny brush… But I like doing inpainting, and working with a tiny brush.

SW – What’s the hardest thing you’ve had to learn in the field of conservation and restoration?

SK – I would say dealing with the clients. I love this work. I don’t see it as hard in terms of technique or skills, although when I was younger, the hardest thing was having to stretch large paintings alone. I felt like I always needed one more person to do it. At this point I have no trouble doing it on my own.

But other than that dealing with the clients can be hard. Art involves people, and there’s a lot of money involved, so that can be difficult to balance. And at times you have to educate people a bit. Sometimes, for example, they want a very aggressive treatment, but I have to tell them no since it will devalue the artwork in the end. Sometimes I have to lecture them a bit. Mostly they listen, often it’s just coming from a place of ignorance. A lot of dealers these days know what they are doing but occasionally I have to deal with people who don’t understand and get angry.

SW – What would be your dream project to work on?

SK – I’ve worked on many different paintings, so I think it’s kind of fulfilled! But one thing I have to tell you is that since I’m Korean, I would love to work on any paintings in North Korea. That would be a dream. But I’m obviously not allowed to go there. People might say, “I want to work on Picasso or Rothko,” but I’ve done all that. So at this point it would be very interesting for me to work on anything in a North Korean collection, though I don’t think that it’s possible. That would be interesting though, don’t you think? It’s such a closed region, and nobody really knows what is going on. I don’t think there is really any conservation there. I would like to go to countries that are not very developed, because conservation tends to exist when people have more money and a more comfortable lifestyle. I want to help countries that don’t have those resources yet because they still have struggling economies.

SW – Thank you very much Suyeon!