"Culture is sensitivity to beauty. And a cultured person is the highest stage of the human being. If everybody were cultured we would have no wars or disturbance. There would be peace in the world." – Alma Thomas, interviewed by art critic and writer Eleanor Munro

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. Our last article in this series introduced McArthur Binion, who, in his 70s, is finally receiving the recognition he deserves. This edition explores the life and art of pioneering abstract artist Alma Thomas.

Who was Alma Thomas?

Alma Thomas (1891-1978) was a pioneering abstract artist who dared make her way in a white, male-dominated abstract art world. She was the first African-American woman to receive a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The year was 1972, and Alma Thomas was 80 years old.

Born and raised in Columbus, Georgia, her family moved to Washington, D.C. to avoid the racial violence in the South. Initially, Thomas studied kindergarten education and worked as a teacher. When she was 30 years old she enrolled at Howard University. There, she became an art major and was the first student to earn a fine arts degree in the department. Thomas taught art at Shaw Junior High, a public school in Washington D.C., for 35 years. All the while, she continued to pursue her own education (a master’s in art education from Columbia University, a painting degree at the American University in Washington where she studied with Jacob Kainen, and a summer of art study in Europe).

Thomas was always active in the local arts community. Throughout the 1930s, she organised community art programs. In 1943, she became the vice president of the Barnett Aden Gallery, dedicated to avant-garde art. This was the first gallery in at-the-time segregated Washington D.C. to exhibit work by both black and white artists. Thomas was also a member of the artist group ‘Little Paris Studio’, started by Loïs Mailou Jones and Céline Tabary. The group created a space for black artists to come together and organise exhibitions.

From representation to abstraction

It was in the 1950s, after taking night and weekend classes at the American University, that Thomas began to shift from representational painting to abstraction. Following her retirement in 1960, at the age of 69, she boldly set out to create abstract paintings. The fact that this was very much a white male playing field did not faze her.

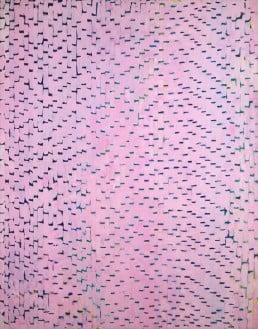

Her brushstrokes became looser and she became much more interested in focusing on fields of colour. In this period, Thomas developed her signature style – short brushstrokes creating patterns of geometric shapes in various rich hues set against solid backgrounds. She often created circular compositions which were inspired by nature and recent developments in space travel.

Colour, nature, outer space

In 1970, Alma Thomas said: “Through color, I have sought to concentrate on beauty and happiness, rather than on man’s inhumanity to man.” Thomas believed that abstract art was capable of transcending political and historical issues. Instead, for her, it touched on deeper and more untranslatable feelings and experiences of humanity. Yet, this is not to say that Thomas wasn’t socially and politically engaged. For example, she was involved in the civil rights movement and recorded her impressions in March on Washington (1964). This is one of her few representational works from the early 1960s. Michael Rosenfeld, her primary dealer, elaborates on Thomas’s artistic positioning: “Her decision to be an abstractionist was in itself a major social-political statement – that a woman of colour can be part of the larger picture of American painting.”

Devoid of overtly political content, Thomas’ work instead focused on the potential and power of colour. It was inspired by nature and by discoveries in space travel, and her own observations of earthly and celestial phenomena. For example, in Snoopy Sees Earth Wrapped in Sunset (1970), a globe made from red, orange and yellow staccato brushstrokes hovers inside a square orange field. Splash Down Apollo 13 (1970) shows mosaic-like concentric circles, made from those same staccato brushstrokes in bright colours. Apollo 12 “Splash Down” (1970) shows what might be the view from a new planet towards new horizons. Small blue and green stripes rise up to create something like a jagged rock, overlooking horizontal stripes of sunset colours.

Thomas’ love of nature pervades most of her other artworks. Often, she was simply inspired by looking at her backyard and observing all the different flowers. Iris, Tulips, Jonquils, and Crocuses (1969) depicts Thomas’ signature style. Tiny broken stripes rain down in verticals in a rainbow-coloured spectrum. In Cherry Blossom Symphony (1973), she sticks to a thick pattern of soft pink stripes over a background of black, blue and green.

In the mid-1970s, Thomas’s brushstrokes started to deviate more and more from the initial ordered lines and verticals. In her 80s by then, she started to create her most confident paintings. These were more free and filled with movement, creating mosaic-type patterns. This can be seen clearly in Hydrangeas Spring Song (1976), where flowering hydrangeas are evoked through differently shaped and sized blue lines and symbols floating, twisting, turning and tumbling through the canvas.

"Her decision to be an abstractionist was in itself a major social-political statement – that a woman of colour can be part of the larger picture of American painting." - Michael Rosenfeld

Late-career recognition, and recent rediscovery

Thomas’s first solo exhibition came in 1960, the very same year she retired and started focusing solely on art. The exhibition was held at the Dupont Theatre Art Gallery. In 1963, her work was exhibited for the first time in New York City at the Martha Jackson Gallery. In 1972, Thomas enjoyed two major solo exhibitions, one at the Whitney Museum in New York City, and one at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington D.C. She was 80 years old at the time. The Whitney retrospective marked an important moment in the history of art. Alma Thomas was the first black woman to ever have a solo-show at the Whitney. Throughout the ‘70s, she continued to show in group and solo exhibitions. Her work was included in the Corcoran Gallery’s 35th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting in 1977.

Yet, after her death in 1978, Thomas slipped from the mainstream art historical canon and her work often ended up in the storage rooms of museums. Though the Smithsonian organised an Alma Thomas exhibition in 1981, the Fort Wayne Museum of Art in Indiana put on a retrospective of her works in 1998, and she has been steadily represented by Michael Rosenfeld gallery for over 25 years (whose latest solo show of Alma Thomas’s works was organised in 2015), it was only in 2016 that the rest of the art world finally started paying more attention to Alma Thomas again.

In 2015, the Obama administration hung an Alma Thomas painting (Resurrection, ca. 1966) in the White House family dining room. By 2016, major exhibitions started flowing in. The Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College and the Studio Museum in Harlem co-organised a major retrospective of Thomas’s works. The exhibition was curated by Ian Berry, Dayton Director of the Tang Museum and by Lauren Haynes, Associate Curator of the Permanent Collection of the Studio Museum. The show opened at The Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery and later moved to the Studio Museum. The Whitney Museum brought out a painting by Thomas from storage and exhibited it beside a Cy Twombly painting. Ian Berry, who curated the retrospective, explains: “Thomas is a legend and a discovery at the same time.” The artist, who made waves in the art world well into her sixties and defied all expectations and conventions at the time, remains an important voice in the history of art and abstraction to this day. Recognition may come and go in the mainstream art world, but it is finally here to stay for Alma Thomas.