Articles and Features

Lost (And Found) Artist Series:

Bill Traylor

By Anthony Dexter Giannelli

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series features artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely overlooked for most of their careers. This week, we feature the groundbreaking work of Bill Traylor, an African-American artist born into slavery in 1853 in Benton, Alabama.

Regarded as an outsider artist – a term often fetishized for its embodiment of pure, untouched creativity, unshaped by structurally influenced thinking of art schools, peer feedback, critique – Bill Traylor began his practice after the age of 80, living much of his life in poverty. After being discovered by a young, white artist and founder of the New South art cooperative, Traylor was solo exhibited only once during his lifetime – a show where nothing was sold – before being buried in an unmarked grave in 1949, leaving more than one thousand works of art behind.

For the decades after his death, Traylor’s work would garner little recognition, being featured in exhibitions which offensively labelled his work “primitive,” ultimately rising to fame in recent years through solo shows at esteemed high art institutions such as the Smithsonian, which devoted to the artist a major retrospective in 2018.

Bill Traylor’s Outsider Life

When in 1862, following the Civil War, the federal government for the first time put an end to slavery, while former slaveowners got monetary reparations for their loss of “property,” newly freed people were either reincorporated back into a system of indentured labour and sharecropping or left impoverished and homeless in Southern urban centres after years of horrific generational suffering.

Bill Traylor’s story and the formation of his distinct visual lexicon begin here, where at the age of 12 he lived through the end of the Civil War at the cotton plantation of George Hartwell Traylor.

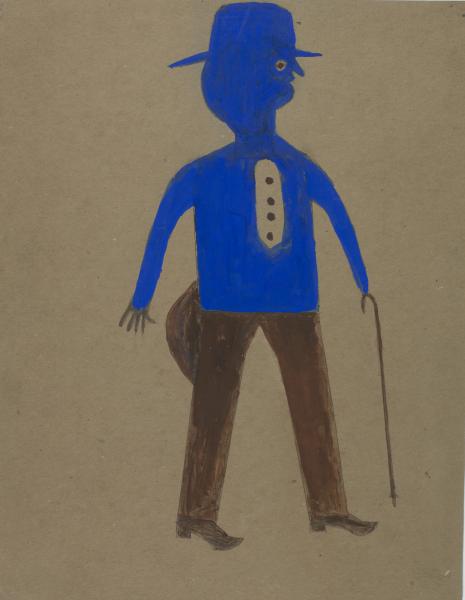

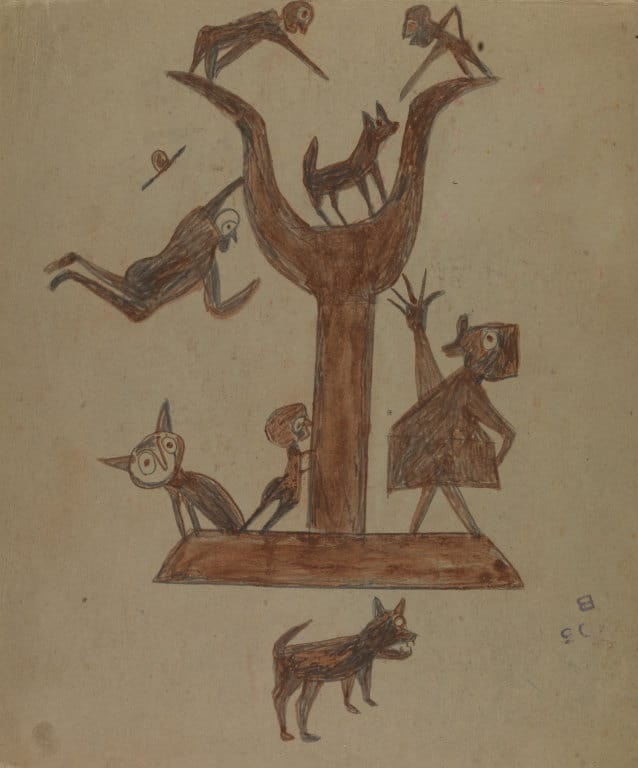

Farm animals resembling dogs or maybe cats, often masked in their true form, constitute Taylor’s artistic imagery, along with men in top hats and pipes, dancing with double-barrel shotguns, canes, and ceramic jugs. His figures move, bend and contort across the compositions on found cardboard scrap pieces. Cobalt blue, red, or black poster paint figures of trees, farmhouses, or even house-men hybrids centre the mainly black or brown monochromatic silhouetted depictions in charcoal or coloured pencil.

Biographically speaking, little factual information about Traylor’s life is known. Through some documented records, we can say for certain how many children he had, who he married, when he died, and where he lived approximately at what times. Any other information pertaining to his life had to be learned through interpretation based on the experiences of others who lived through similar conditions or through a handful of secondhand accounts. What we do have, however, is a wealth of visual and emotional documentation of his lived experiences as his scenes evoke his feelings during a time of tumultuous change, from the difficulties of Jim Crow segregation, lynchings, and homelessness, to his affection for his family and rural life.

Each of his works offers a window into a truly personal story unique to Traylor, a story whose uniqueness garnered the attention of Charles Shannon, a white artist passing by the then homeless, 80-year-old Traylor in the Monroe Street neighbourhood of Montgomery, Alabama. Shannon sponsored Traylor through paints and supplies and exhibiting his work through a singular solo exhibition at Shannon’s Cultural centre in 1940. This continued well after Traylor’s death in 1949, where after the unfortunate loss of a significant amount of Taylor’s works, Shannon retained the majority of his existing oeuvre.

Recognition and Finding a Just Legacy

Today, Traylor has earned fame for his originality, use of form, and storytelling. However, at times in the past, his story has seemed lost both literally and figuratively. In fact, not only did his groundbreaking perspective lose to the zeitgeist for decades but also, in a physical sense, all works created after 1942 were destroyed, largely by the real estate firm who sold his daughter’s home.

Despite a missed opportunity – in 1942 then MoMA director Alfred Barr had in fact offered to buy Traylor’s works for 1 or 2 dollars per piece to be held in the museum’s collection – today, the artist’s works circulate through blue-chip galleries such as David Zwirner and are sold for top prices on the secondary market, generating continued wealth, unimaginable to Traylor during his lifetime.

Traylor’s work has also evolved in interpretation, contextualization, and categorization numerous times: from folk art, outsider art, modern art to fine art. Traylor depicted the world as he saw it, through his experiences and lived story. Regardless of the art world’s shifts in interpretation, over the years the figures in charcoal and poster paint on discarded cardboard remain unchanged. Posthumously, Traylor’s scenes tell us as much about his personal story as they act as a mirror to society, whose evolving interpretations reveal our shortcomings and the injustices faced by the artist, his family, and his community even to this day.

Now that deserved appreciation has indeed been found and is growing ever more through critical acclamations, how can the art world pay propper hommage and justice to a fascinating figure that was saved from obscurity only because he first found recognition through white benefactors and audiences?

As recently as 1992, Traylor’s over 40 living descendants sued Charles Shannon for ownership of his remaining works and were granted a mere 13 works. Though Shannon himself died four years after this case, most works are still represented through the Charles E. & Eugenia C. Shannon Trust. With much of his legacy in the hands of the trust of the white artist who first “discovered” Traylor, what can be said about justice for Traylor’s works?

His story fits well into the box of his outsider contemporaries, who lived in obscurity and hardship only to be celebrated in death. After a life of struggle, neither he nor arguably his descendants have rightfully experienced firsthand the true benefits of his visionary production. However, his work will undoubtedly continue to garner attention for years to come. The work of a man born into slavery nearly 200 years in the past will continue to show us how far we have come and keep us questioning how far we still have yet to go.

Relevant sources to learn more

Traylor’s life has recently been honoured in the film Bill Traylor: Chasing Ghosts, where a major focus is placed on previously overlooked cultural context and commentary on the wider social struggles faced by African Americans in the US South.

A Short History Of the African Diaspora Through the Eyes of Its Visual Artists

Read our previous editions of Lost (and Found) Artists:

Harold Shapinsky

Lee Krasner

Rose Hilton