Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Gertrude Abercrombie

By Shira Wolfe

“I am not interested in complicated things nor in the commonplace, I like to paint simple things that are a little strange.” – Gertrude Abercrombie

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. The focus of this edition is American Surrealist artist Gertrude Abercrombie, known as the “queen of bohemian artists,” who lived and worked in Chicago and was part of a lively circle of artists and jazz musicians. Despite Abercrombie’s prominence in the artistic milieu of Chicago, her paintings remained little-known outside the Midwest until fairly recently.

Gertrude Abercrombie – An Introduction

Gertrude Abercrombie (1909-1977) was born in 1909 in Mercer County, Illinois. She was the only child of travelling opera singers who eventually settled in Chicago. Abercrombie graduated from the University of Illinois with a degree in romance languages before finding her true calling: painting. She was never classically trained, but took classes here and there, at the Art Institute and the American Academy of Art in Chicago. In the 1930s, Abercrombie worked for the WPA, which gave her the validation of being regarded as a real artist.

She also attended the Grant Park Open Art Fair, which was held in conjunction with the Century of Progress Fair. Almost every artist in Chicago was there, and Abercrombie would set up all her paintings around her old Rolls Royce. She quickly became an unmistakable part of the Chicago art landscape.

In 1935, Abercrombie was introduced to Gertrude Stein through novelist and playwright Thornton Wilder. Stein told her she had to “draw better,” and Abercrombie took her advice to heart, developing her Surrealist style that she would become known for. After this, her career started to take off, and she won her first award at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Gertrude Abercrombie’s Style and Themes

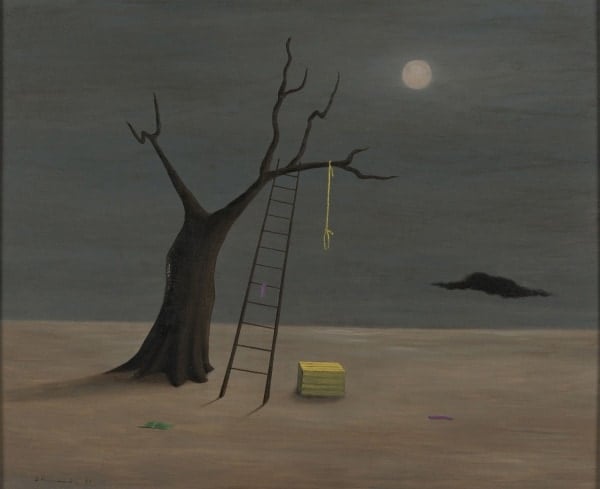

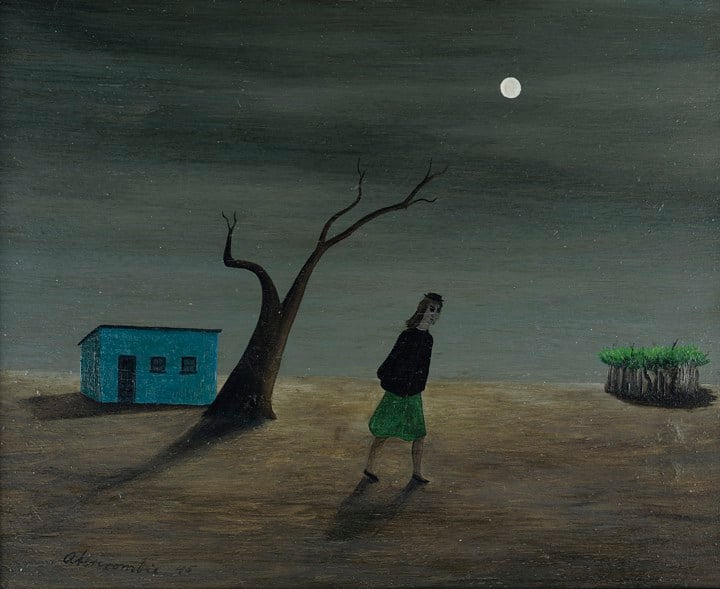

Abercrombie’s early style was loose and painterly, but over time she developed a precise Surrealist style that drew on the mysterious, dreamy realm of the subconscious. She established a repertoire of personal themes and symbols which included cats, clouds, the moon, ostrich eggs, doors, lightning bolts, rocks, seashells and self-portraits (which never really looked like her).

Her symbols were placed in barren, mostly nocturnal landscapes and spare interiors, reflecting her recurring dreams, her fears and her obsessions. Abercrombie herself liked to refer to her paintings as “off the beam.” Though she was clearly indebted to the work of the great European Surrealists René Magritte and Giorgio de Chirico, Abercrombie’s Surrealism was largely homegrown, inspired by the particular atmosphere and culture of her Midwestern surroundings.

Abercrombie’s works were always self-consciously performative and autobiographical. She once said: “It is always myself that I paint.” As such, the figures in her paintings mostly represent Abercrombie herself, and she did a large number of self-portraits in her lifetime, despite the fact she considered herself to be unattractive. These self-portraits have come to be known as “Psychic Self-Portraits.” Abercrombie never really attempted to capture her actual features, but was instead interested in depicting her mental or emotional states.

During her prime years of artistic output, Abercrombie became known for her door paintings. The doors, placed outside in enigmatic landscapes settings, act like mysterious barriers. She explored these symbols that usually signify an interior space, but came to represent an idea of the access to what lies beyond. With these paintings, Abercrombie subverted both the genres of landscape and domestic interiors, creating a new realm akin to the one associated with the Belgian Surrealists. The door paintings also showed that despite her role as the social hub for artists and jazz musicians in Chicago, there was a side to her that was introspective, solitary and hidden to others.

“She was the first Bop artist in the painting world. Bop in the sense that she has taken the essence of our music and transported it to another art form.” – Dizzy Gillespie

Gertrude Abercrombie and Jazz

In the mid-‘30s, Abercrombie became involved with the jazz scene and began hosting parties for all the creative spirits around at her home. People started referring to her as “the queen of the bohemian artists.” She entertained many jazz musicians at her home, throwing parties on Saturday evenings and jam sessions on Sunday afternoons, which attracted some of the brightest stars in jazz music at the time. Her friends included the likes of Dizzy Gillespie, Sonny Rollins, Charlie Parker and Sarah Vaughan. Gillespie even played at her wedding, and jazz composer Richie Powell wrote a song inspired by her called “Gertrude’s Bounce.”

The jazz musicians had a deep respect for Abercrombie, and considered her to be doing something akin to bringing jazz into the realm of painting. When responding to Gillespie’s statement that she was the first Bop artist in the painting world, Abercrombie once said: “I told him that I invented the term “Bop” for my art, because there is a thing called Op Art and Pop Art, but I said, mine is “Bop Art.” I just invented that term in the art sense, but oh no no, he and Charlie did the Bop for music.”

What Gillespie was getting at was the improvisational component to Abercrombie’s artwork. She was a free spirit who painted what she felt, exactly how it came to her in the moment.

Recognition and Legacy

If the “queen of bohemian artists” was so beloved and well-respected during the hey-day of Chicago’s art and music scene, then why has she remained such an under-appreciated and overlooked artist for such a long time? Elmhurst Art Museum’s Executive Director John McKinnon names several reasons: first, she was not associated with any of the large artistic movements of her time – although she is now considered a Surrealist artist, she was not clearly associated with Surrealism during its pomp, partly due to her geographic remove from its epicentre; second, she was a woman during a period when female artists were simply overshadowed by their male contemporaries. However, Abercrombie always managed to sell her paintings. She even came up with a way to sell more works in the ‘40s, by starting to produce tiny pieces (3.8 x 3.8 cm) which she could sell for lower prices.

In the last years of her life, she put a lot of effort into getting her finest works back. She reacquired some of the works she had sold in order to create a proper legacy.

Illinois State Museum hosted a retrospective of her work in the early ‘90’s, but it hasn’t been easy to see an in-depth overview of her work until the 2017 Elmhurst Art Museum exhibition Gertrude Abercrombie – “Portrait of the Artist as a Landscape.”

Since then, her works have been shown for the first time in New York since 1952, at Karma Gallery. Her works were also included in the group exhibition (27 July – 7 September 2019) “A Cloth Over a Birdcage” at Château Shasso in Los Angeles. Just before she died, in 1977, Abercrombie received a retrospective exhibition at Hyde Park Art Center in Chicago. In a conversation with the author and broadcaster Studs Terkel, Abercrombie said of attending her opening: “I will go out either in a blizzard or in a blaze of glory.” Poetic, tough, and humorous till the very end, just like her paintings.

Relevant sources to learn more

For an excellent insight into Gertrude Abercrombie, her art and her bohemian lifestyle in Chicago throughout the decades, listen to the WDCB broadcast “The Arts Section,” which discusses Abercrombie and the 2017 Elmhurst Art Museum exhibition.

For other sources, see: