Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Hannah Ryggen

By Shira Wolfe

“Equality for all mankind. We are all flesh and blood, just the same.”

Hannah Ryggen

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist series features artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their careers. The Swedish-born Norwegian textile artist Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970) was well known in Scandinavia in the 1950s and 1960s for her beautiful tapestry works carrying radical political statements against fascism, nazism and the atrocities of war. Yet Ryggen’s work became increasingly categorised as craft after her death in 1970, and it took many years for it to be appreciated for its importance again. Rediscovered thanks to the 2012 dOCUMENTA (13), Ryggen is now considered one of the most important figures in the history of Scandinavian art.

Who Was Hannah Ryggen?

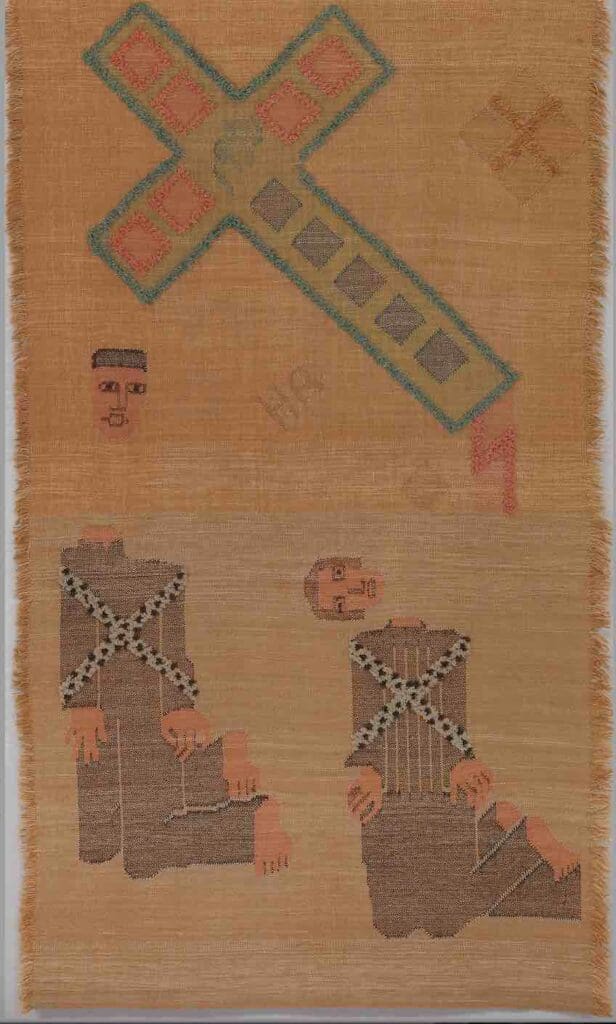

Born into a working-class family in 1894 in Malmö, Sweden, Hannah Ryggen trained to become a teacher. She taught during the day and took art classes in the evenings with the artist Fredrik Krebs. On a study trip to Dresden, she met the artist Hans Ryggen. They married and moved to a small farm in Ørlandet, Trøndelag County in Norway. The couple worked on the farm, and when that work was done, they worked on their art. Ryggen taught herself how to weave on a standing loom that her husband had built for her. Weaving allowed her to create monumental artworks that liberated her from the condescending view of women artists and their paintings at the time. She wished to be able to address any topic she was concerned with, particularly political issues that she felt strongly about. The nature of working with the loom (by default creating strong angular shapes) helped Ryggen discover and develop a fascinating combination of abstraction and figuration.

Weaving Activism

Ryggen was deeply committed to the resistance of oppression and the fight for justice and equality. “Every man and woman, whether rich or poor, ought to be raised capable of two things: producing their own food and supporting themselves. It is an indignity that some serve others. Everyone should work, no one should be above another. Equality for all. We are all flesh and blood, just the same,” she believed.

In her tapestries, woven in her remote little farm on the Norwegian coast, she addressed important political events and human rights injustices around the world. Her tapestry Ethiopia (1935) condemns Mussolini’s occupation of Ethiopia in 1935 and was shown in the 1937 Paris World Exposition along with Picasso’s Guernica – although the part of the tapestry showing Mussolini’s head being pierced by a spear was rolled up during the exhibition, as the organisers feared it might insult the Italian state power. Other topics Ryggen wove into her tapestries were the rise of fascism and nazism; for example, she depicted her husband’s internment in Grini camp, a Nazi camp in occupied Norway. She was also concerned with the effects of the Great Depression on ordinary civilians, the post-war growth of nuclear power, and made striking visual statements against the Spanish Civil War and the war in Vietnam.

Ryggen’s art is at once spellbinding, uncompromising, humorous and tender, filled with her powerful sense of justice and empathy towards mankind, animals and nature. There is a real power in how this artist, far removed from the large political and cultural centres of the world, managed to address personal and universal topics with such clarity and insight in this visually majestic way.

“As far as the weaving technique is concerned, it is very simple: a horizontal line is interlaced with or passed around a vertical line. (…) I am limited by the vertical warp, you by the block of stone, and the resistance involved is something we both have to understand and submit to.”

Hannah Ryggen, letter to the sculptor Dyre Vaa, 1946

Process and Technique

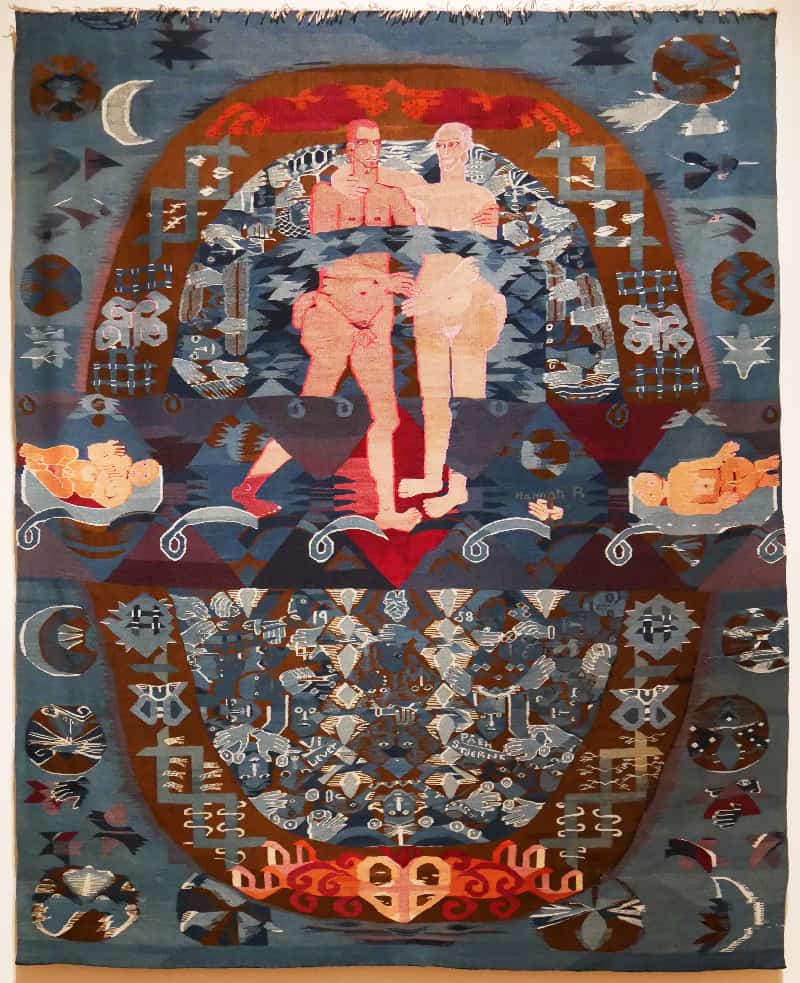

Ryggen took control of the entire artistic process, carding, spinning and dyeing the yarn herself. She developed a deep understanding of the chemical processes of colouring, using natural plant dyes and even urine in order to make her coloured yarn. Pot blue, also known as “pee blue”, became her favourite colour to work with, representing positivity, longing and dreams. She made the colour with urine, and always kept a pee bucket around to collect more.

In a letter to the sculptor Dyre Via from 1946, she writes: “As far as the weaving technique is concerned, it is very simple: a horizontal line is interlaced with or passed around a vertical line. Triangular sections of the tapestry are built up roughly like this [sketch]. This is how the Baldishol and Coptic tapestries are made, and mine as well. I am limited by the vertical warp, you by the block of stone, and the resistance involved is something we both have to understand and submit to.”

The Rediscovery of Hannah Ryggen

Ryggen became well known in Scandinavia in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1958, she was commissioned to create a work for Erling Viksjø’s new government building Høyblokka (H-block) in Oslo. This resulted in her large tapestry We Live On A Star, filled with lots of her beloved blue colour. The naked couple and the children are standing on planet Earth, floating in space with other planets and stars. They symbolise the eternal renewal of life. The tapestry was damaged during the terrorist attack by Anders Behring Breivik in 2011. His fascist ideologies had been exactly what Ryggen was fighting against all her life through her art. The tapestry has since been restored.

Since her death in 1970, Ryggen’s work fell out of fashion for a period as people started categorising it as craft, instead of appreciating it as the great art that it was. In part thanks to her inclusion in the 2012 dOCUMENTA (13), the importance and timelessness of her art were rediscovered. Since then, major exhibitions were organised at the Malmö Museum of Contemporary Art in 2015, at the Oslo National Museum in 2015, at Modern Art Oxford in 2017-2018, and at SCHIRN in 2019-2020. Today, Hannah Ryggen is considered one of the most important Scandinavian artists and a true pioneer of textile art.