Articles and Features

Modes Of Display: The Changing Face Of The Exhibition Format

By Adam Hencz

Exhibitions have become the medium through which most art becomes known.

— Bruce W. Ferguson

Exhibitions are woven into the fabric of contemporary culture. Works of art are created to be seen. Art triggers emotions, we ascribe them meaning, interpret, criticize and discuss them, or just look at them merely for aesthetic appreciation. From shows that amuse through installations to conceptual spaces, it is possible to identify the shift in taste at key times in the rich history of the modern period. Some historical exhibitions marked the beginnings of art movements and in the process signalled a paradigm shift for the characteristics of an exhibition, others challenged established aesthetic ideology or added new elements to the language of display. All these components that together constitute the prevailing format where the meeting of art and the public takes place, certainly evolved in a non-linear way – the role of the artist themselves, shifting definitions of gallery and institution, plus socioeconomic contexts all challenged and changed the way we look at and perceive art.

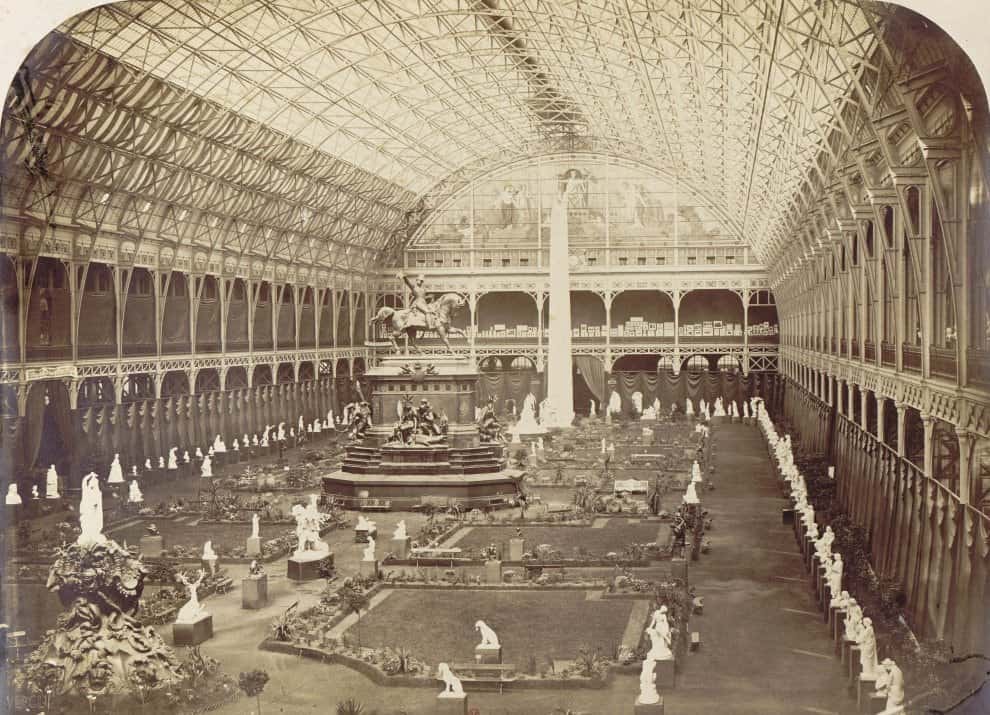

Cabinets of Curiosities and early exhibitions

In the post-mediaeval period, monasteries, churches and the wealthy maintained collections of religious or historical relics and works of art and antiquities. The collections grew into “cabinets of curiosities”, the Wunderkammer of the 16th and 17th centuries, the precursors of the state galleries and museums. These early forms of unified collections filled rooms of their owner’s estate and reflected not only the artistic and scientific interests of the patron but were symbolically representative of things like discovery, power and control, over things like commerce and colonial expansion. Rulers and merchants ensured their collections were well documented, which in turn catalysed a new genre of painting specifically about collectors and their holdings. The first illustrated catalogue of a major painting collection is the fruit of a decade of work in the mid 17th century by David Teniers the Younger, in which he documents Archduke Leopold Wilhelm’s collection. The artist also painted a series on the Archduke’s gallery in Brussels where his collection was put on display for curious groups of aristocrats to visit.

The Paris Salon

The first exhibitions sponsored by any state or government originated in 1667 when Louis XIV sponsored an exhibition for works by members of the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. The initially sporadic exhibition moved to the Salon Carré in the Louvre in 1725 and from 1737 became an annual cultural event of the bourgeoisie. From 1748 artists and their works had to be approved by a jury, typically recruited from members of the Academy. The shows were colourful, luxuriant and the milieux was much closer to the fabric of upper-class social life and its modes of socialisation than it was an attempt to critique or disrupt modes of display. The walls were covered by paintings from ceiling to the floor, arranged in strata according to their genre, with no space in between them. The gallery visitor, astonished by these monumental displays, perceived the gallery as a unity and a universe of paintings rather than as a place to interpret individual works. These early iterations of the exhibition format were at the service of social ceremony and ritual, and whilst they advocated the showing of art objects to the public, they largely remained accessible only to a certain elite.

The Salon also pointed in a direction favorable to both acquisition and intellectual exchange, whilst also brought a changing identity and role for the artist, leading many to abandon the court in order to instead become an exhibition artist. The Salon’s prestige was undisputed, and these exhibitions began to serve as the medium through which most art became known.

Salon des Refusés, 1863

For the 1863 Paris Salon exhibition an enormous number of works were submitted, leading most of the almost 3,000 pieces to be rejected by the jury, that would classify works following a specific hierarchy. Independent artist groups were formed and did not yield to the dictates of institutional taste and its prevailing aesthetic. Among the rejected artists were Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro and Johan Jongkind, whose protest reached Napoleon III. The Emperor offered a compromise, and allowed a parallel exhibition to be held for the refused works at another part of the Palais de l’Industrie.

The rejected artists’ Salon became known as the Salon des Refusés, a counter establishment exhibition that paved the way for a burgeoning avant-garde and bolder methods of exhibitions. Connecting relationships between individual artworks started to appear and certain constants and themes framed shows into a coherent whole. The audience could experience unusual paintings and sculptures but within an identifiable setting, whilst considering subjects that connected those artworks. This was the dawn of curatorial oversight. Artists also began organizing their own shows within environments inspired by the studio or workshop, and which were readily available to them and to the mercantile class of collector with which they had an increasing affinity and access to. The very first exhibition of the Impressionists, held in April 1874, was arranged at the studio of the photographer Nadar.

The format of communication which Germano Celant called the discipline of exhibiting started to shift emphasis away from the mesmerizing quantity of artworks in galleries for the gaze of the privileged and towards the identification of the subject of the exhibition and themes that connected the works within them. Things like their juxtapositions and associations, the space between them, their arrangement, framing choices, even the walls that confine them – all of these elements became increasingly subject to interpretation, analaytical thinking and thematic discussion.

Early 20th Century Exhibitions

The exhibition spaces of the nineteenth century created different arenas of display: artist-led exhibitions, studio showings, galleries and museums, private collections and trade-fair installations.

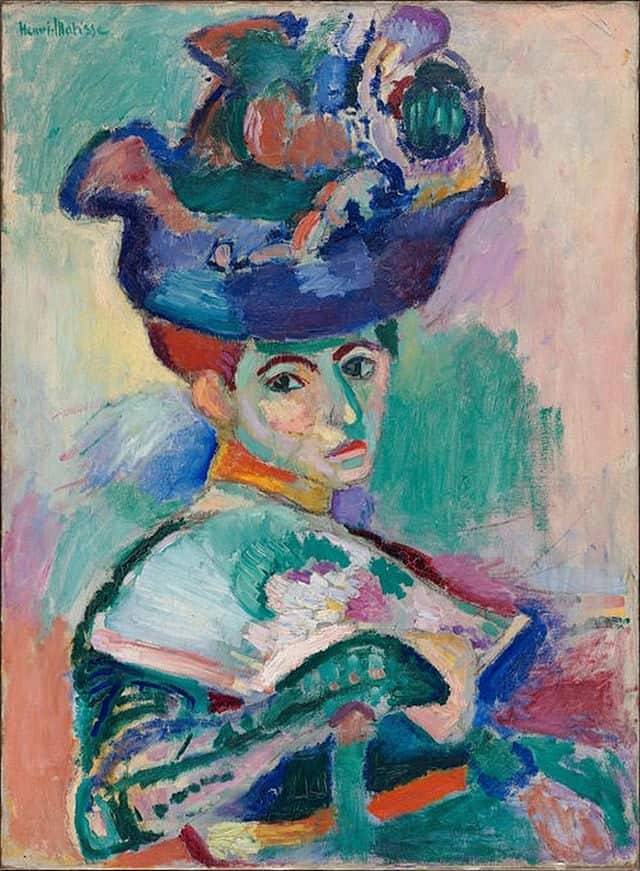

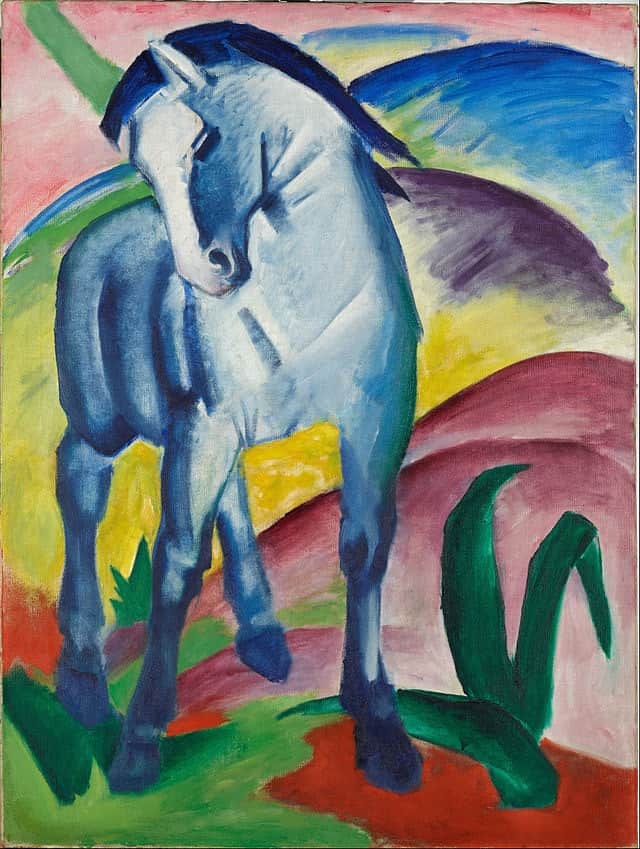

The early 20th century saw a proliferation of shows grouped by communal sympathies and movements. This thematic approach brought unfamiliar objects to the audience in a provisional context, creating platforms for artists statements and gateways to the establishment of the art world as we know it today. The Salon d’Automne was an annual exhibition in Paris that began in 1903 and its third edition reflected a classic group show of modern art with a concentration of Fauvist works in room seven. Expressive painterly quality and strong color was emphasized in their style which also served as an inspiration for the inaugural Blaue Reiter exhibition in Munich in 1911, a group which pushed further towards abstraction.

In 1913 an art exhibition opened in New York city that marked the dawn of modernism in America. The Armory Show shocked the American audience and had a profound influence on American artists and collectors. Two thirds of the exhibition content was by American artists, but it was the European artworks by Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cézanne, Picasso, Matisse and Duchamp that caused a sensation, changing notions of what an artwork could be and the perception of beauty forever.

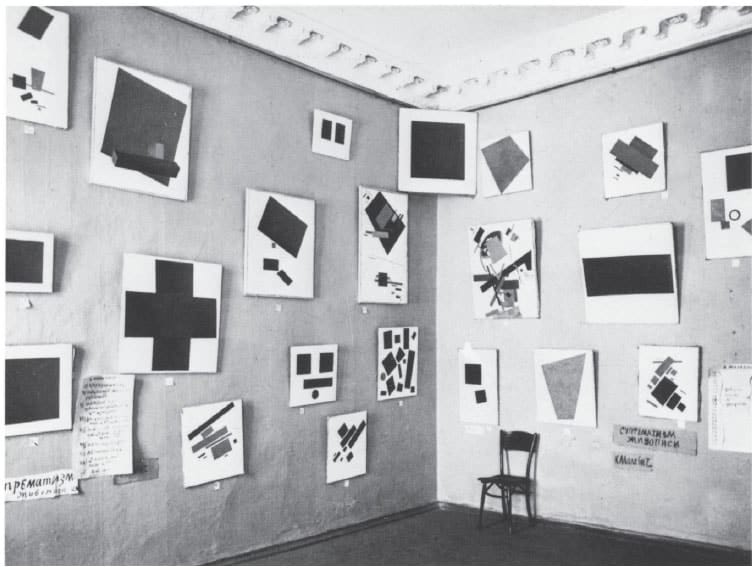

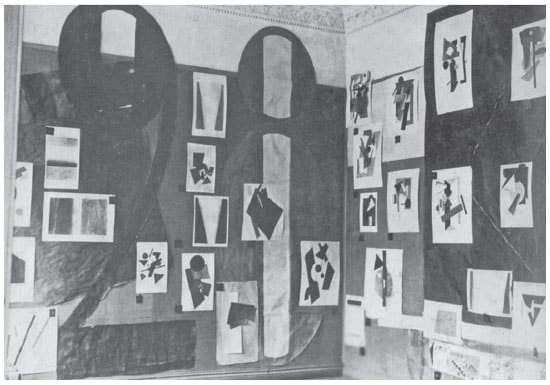

Petrograd, December 1915/January 1916.

The avant-garde continued to relentlessly experiment with the notion of display. Installation started to matter and became a linguistic arena meditating between art and architecture both with the arrangement of visual materials and the organization of spaces. In 1915, in Saint Petersburg, Kasimir Malevich published his manifesto, The Last Futurist Exhibition of Pictures 0,10 in an unexpected manner that resonated with the form of his non-objective art itself. Malevich’s display later inspired Ivan Puni’s installation in 1921 for the Sturm Gallery in Berlin.

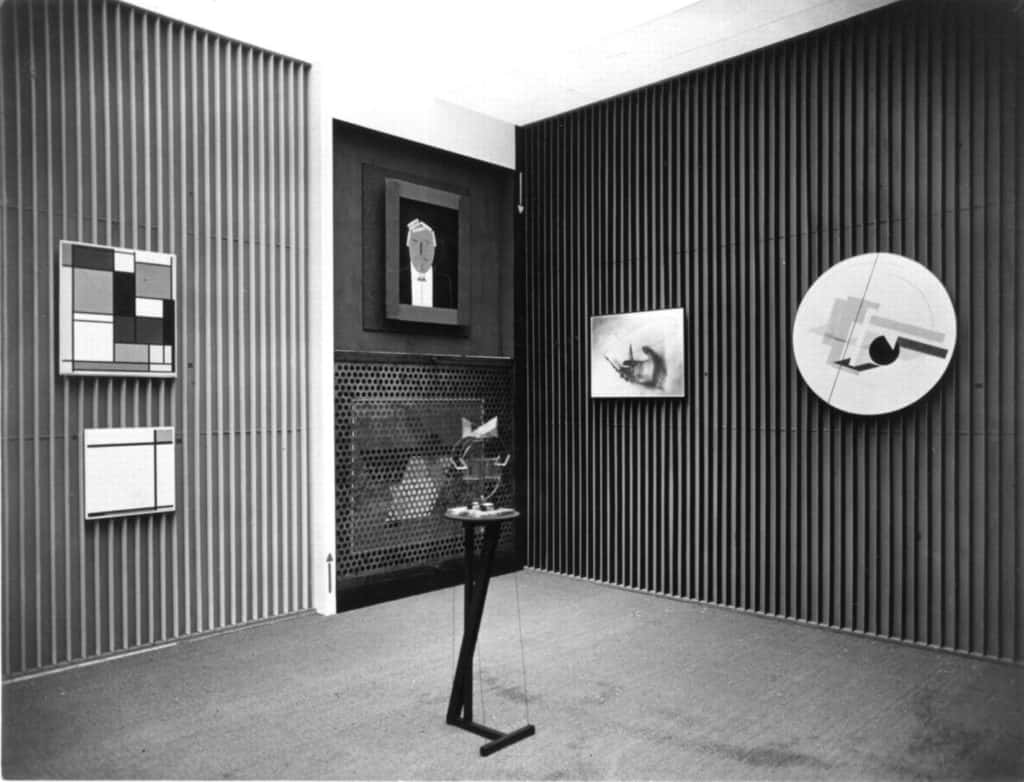

Most pioneering exhibitions were framed within art galleries and studios rather than given the space by museums, which at this time remained preoccupied with the display of their own collections. Stark contrasts became clearly visible in 1927 in the Provincial Museum in Hanover. In a dedicated museum room El Lissitzky installed the Kabinett der Abstrakten, an exhibition space with modular walls. Meanwhile in the rest of the building works of art were conservatively hung. El Lissitzky had created a tool to encourage new reading, understanding, misunderstanding and new life for the museum collection.

Photograph of the abstract cabinet show works by Piet Mondrian, Mies van der Rohe and others.

Duchamp’s work saw the beginnings of regarding gallery space as dialogically related or equivalent to the art it hosts.

— Brian O’Doherty

The International Exposition of Surrealism of Paris in 1938 was to mark the complete unfolding of the surrealist manifesto, whilst also creating the kind of immersive environment galleries and museums continue to strive for today. Duchamp created a synaesthetic atmosphere and confusing experience to arouse desires. In the dim light of an allegedly coal-fired stove, visitors had to navigate themselves with the aid of a flashlight, so they could better see the artifacts on display. Stuffed coal bags were suspended from the ceiling, the odour of roasted coffee filled the air and the laughter of asylum inmates evoked a multisensory experience.

In spite of the rise of experimental movements, the 1930s and 1940s also strengthened conventions of display and contributed to standardizing single-row eye-level hanging, institutionalized the use of white walls in galleries and created a sterile context where all the noise of the outer world is completely filtered out. The white cube became the most widespread display practice in the field of contemporary art, and despite many addressed alternatives, it is still the prevailing mode of display and way we perceive and consider art.

Relevant sources to learn more

Bruce Altshuler exhibition cataloge: Salon to Biennial: Exhibitions that Made Art History (1863-1959)

ONCURATING.org Issue 6: 1,2,3, — Thinking about exhibitions