Articles & Features

From Museum to Basement and Back: The Incredible History Of A Russian Avant-Garde Treasure

“It is a very important discovery which will not only bring new works to light but will also tell the fascinating story of the travelling exhibitions in Russia in the first years after the October Revolution”

Natalia Murray

What happens when you decide to store an object in the basement, then forget about it and eventually find it decades later in total astonishment, like some kind of treasure? Multiply that feeling of surprise and wonder and imagine the amazement that the art historian Andrey Sarabyanov must have experienced when realising that a number of artworks hidden in the basement of the remote Yaransk Local Lore museum – hundreds of miles away from Moscow – are actually pieces by renowned Russian artists. Last week the Russian avant-garde expert revealed to the press the identification of dozens among these works, including three watercolours by Wassily Kandinsky, a gouache by Varvara Stepanova, and a painting on cardboard by Alexander Rodchenko, a previously unknown work which is already undergoing conservation treatment.

The discovery of hidden artworks is certainly an exceptional event, but perhaps not as rare as one might think. In Europe the phenomenon is mainly related to Nazi-looting: it’s estimated that the Nazis, between 1935 and 1945, stole one-fifth of all the artworks in Europe, an approximate figure of 650,000 works pillaged from museums, churches, and private collections of Jewish mercantile art patrons. It is therefore not entirely surprising when some looted pieces reappear more or less by chance somewhere in Europe.

The most impressive case to date has been the recovery of a trove of around 1,500 works, worth more than a billion dollars, in a flat in Munich owned by the son one of the most notorious art dealers employed by the Third Reich. The “collection”, also known as the “Gurlitt Hoard”, included masterpieces by Picasso, Matisse, Monet, Chagall, Dürer, and Delacroix.

While seeking lost art, it is not always necessary to go looking too far. Just last year, a gardener clearing up the ivy on a wall of the Ricci Oddi modern art gallery in Piacenza, Italy, discovered a cavity with a bag in it. To his surprise, the bag contained what has been confirmed as Portrait of a lady (1916-1917), an authentic Gustav Klimt, which had been missing from the museum for twenty-four years.

If, however, some of these examples involved theft, this does not seem to be the case for the Russian avant-garde works discovered at the Yaransk Museum. How can it be possible that remarkable artworks were stored (or maybe hidden) in a museum basement and later forgotten as if they had vanished into thin air? To better understand this, lien is necessary to step back to the origins of the Russian Avant-garde.

The Russian Avant-garde

The “Russian Avant-garde” is often discussed as if a homogenous whole, but the art that flourished in Russia in the first decades of the 20th century is better defined by plurality: breaking it down into temporal phases, as well as in terms of style and content.

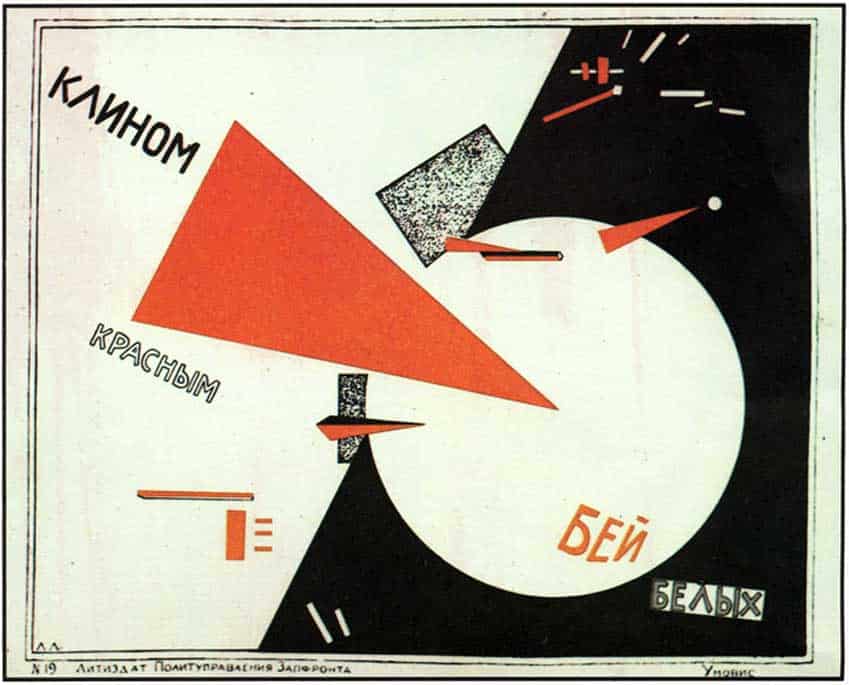

Its origins can be found in the second half of the 19th century, when the Peredvizhniki (literally “Itinerants”), a group of realist artists, formed a cooperative in protest against academic restrictions and arranged travelling exhibitions to circulate art outside the capital with a renewed political and social connotation. Thanks to this new open attitude, the various avant-garde strains that came to Moscow at the beginning of the new century, from Paris and the rest of Europe – from the Fauves to Cubism – were warmly embraced by Russian artists, but then were developed further, reflecting the social fervour that had come to encompass every aspect of life. Russia thus became the ideal hub for the flourishing of cutting-edge movements; first of all, the Neo-Primitivism of Michajl Larionov and Natalja Goncharova, concerned with the theme of folklore and the roots of Russian culture; then the progressive abandonment of figuration led to the experimentation of a new expressiveness, shapes became simple and art reduced to essentials. Thus originated Kandinsky’s pioneering abstractions, the Constructivism of Vladimir Tatlin, Alexander Rodchenko, and El Lissitzky, as well as the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich, Ivan Puni, and Olga Rozanova.

If the Russian Avant-garde had anticipated the October Revolution, it later represented an intellectual response to it and, when in 1917 the revolution broke out, the acceptance of revolutionary ideas by artists did not lead to a standardization of their positions. On the contrary, the debate instead swirled around what form a new “people’s” art should take.

Not surprisingly, the group of paintings found in Yaransk seems to be part of a 1921 travelling exhibition organised by the early Bolshevik government, reminiscent of the Peredvizhniki experience. More than 350 works by contemporary artists toured the region by horse-drawn cart. According to records, some of the works remained in Yaransk, while others were transferred to Kirov, the regional capital, and are currently displayed as part of the Vasnetsov Brothers Art Museum’s collection.

As the years passed and the political situation deteriorated, attitudes towards art started to change: the creative freedom sought by avant-garde artists and their tendency toward abstraction was accused of being incomprehensible to the masses and, consequently, elitist. By the end of 1932, Stalin’s brutal suppression had drawn the curtain down on the Avant-garde. Art returned to being purely figurative, with only a single subject permissible, that of communism’s nobility, with all works needing to somehow embody this ideal. A single style was permitted by the authorities; the era of Socialist Realism had begun.

Faking the Russian Avant-garde

In the last decades, a phenomenon has emerged in the Russian art world, causing perplexities, as well as a certain embarrassment for cultural institutions.

In 2009, an exhibition of Russian avant-garde paintings with a focus on Aleksandra Ekster, held at the Château Museum in Tours, France, was abruptly shut down three days before the expected closing date, when a well-known art expert claimed that 190 out of 192 works were fakes. And this was not the first time a museum found itself abashed by supposedly fake Russian avant-garde pictures. Only a year earlier, the Bunkamura Museum of Art in Tokyo was compelled to remove five works attributed to Chagall, Kandinsky, and Ivan Puni from an exhibition lent by the Moscow Museum of Modern Art (despite the claims of authenticity by the Russian museum).

Even more recently, in 2018, the Ghent Museum of Fine Art in Belgium cancelled a show titled “Russian Modernism, 1910–30” revealed to be full of counterfeit works. The museum’s director was suspended and, latterly, the collector couple who lent works to the Belgian museum, Igor and Olga Toporovsky, were arrested and are currently facing allegations of fraud, money laundering, and forgery.

Of course, the possibility to be assailed by fake paintings can occur with art from any period, but it is alarming how frequently this happens when it comes to works allegedly created during the Russian Avant-garde period. Even a supposed masterpiece like Black Rectangle, Red Square, thought to be created by Kazimir Malevich in 1915, was found to be a forgery. Scientific analysis revealed that the piece could not have been painted before 1950, and most likely originated between 1972 and 1975, making it clear that it could not be Malevich’s hand since the artist died in 1935.

The root of the issue is the fact that the provenance of Russian avant-garde art is, for the most part, a black hole. In the aftermath of the Revolution, as censorship measures increased, artists either had to conform to Socialist Realism — as the state propaganda machine demanded — emigrate, or work in secret. This explains how non-compliant works — especially the ones belonging to the Avant-garde — ended up in museum basements.

When in the 1970s, and even more so after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the market for Russian avant-garde art began to develop, many legitimate works began to sprout, often devoid of proper provenance documentation.

Moreover, as a new generation of wealthy Russian collectors emerged, prices increased immeasurably. So much so that a painting by Malevich set a world record for Russian art when sold for $60 million at Sotheby’s in 2008. The opportunism of this situation did not go unnoticed by counterfeiters who promptly began to take advantage of it.

Once again, only the close collaboration between scientific investigation and art historical expertise can solve the problem and put an end to the seemingly endless string of unmasked fakes.

Coming back to the Yaransk trove, Andrey Sarabyanov – who has already fought himself against the abundance of Russian avant-garde forgeries – defends its authenticity and states that he is open to technical analysis.

Moreover, together with Kirov museum’s director Anna Shakina, and Natalia Murray, a lecturer at the Courtauld Institute of Art in London, Sarabyanov is planning to eventually reunite the works divided between Yaransk and Kirov and recreate, as far as possible, the 1921 exhibition.

Relevant sources to learn more

Database of lost art

Unknown or Unreal? The Shadow on Some Russian Avant-Garde Art

The Art of Forgery – Art Forgers Who Duped The World