Interview with Niels Borch Jensen, founder and director of Niels Borch Jensen Gallery & Editions

A Visionary Artisan Throughout 40 Years

Niels Borch Jensen Gallery & Editions has drawn to its creative laboratory on the small island of Amager, a neighbourhood in Denmark’s capital Copenhagen, a long list of talented artists: Keith Haring, Georg Baselitz, Tacita Dean, Olafur Eliasson, Per Kirkeby, Julie Mehretu, and Tal R. World-famous among connoisseurs, but below the radar of the general public, the 700 square metre print studio has influenced the fine art of printmaking during almost 40 years. We had the pleasure of stepping into the studio of Niels Borch Jensen, to talk about his passion for printmaking, his contribution to the ongoing development of the medium and the collaborations with some of the most celebrated artists.

- Name: Niels Borch Jensen (b. 1952), founder and director of Niels Borch Jensen Gallery & Editions

- Location: Copenhagen, Denmark

- Founded in year: 1979

When did you first become aware that you had a special affinity for print making? Did some specific aspect of it catch your attention?

My interest in print making started early in my life. I drew a lot when I was a child and have always had a creative drive, but two events in particular were decisive. First of all, when I found books on etchings by among others Rembrandt, Albrecht Dürer and Francisco Goya at the local library. The intimacy I felt in the several hundred years old etchings in those books was captivating in a way that could not compare to the other art books I studied at the time. Second of all, I had a young, enthusiastic art teacher in upper-secondary school who acquired a converted shoemaker’s press and encouraged me to try doing prints.

My experience of learning things had until then been mainly focused on books, and now I suddenly had to use my senses. When you work with a roller, there is a specific sound that indicates whether the resulting print will turn out successful or not, and that is something you cannot read in books. It was a completely different experience from what I was used to. During the last years of my time at the upper-secondary school, I discovered that I wanted to work with graphics more seriously, and therefore my dad helped me invest in another shoemaker’s press that I installed in my room and worked on at home. I was around seventeen then, and the absorption by the craft has been with me since.

What got you started and what motivated you to open your own print studio?

I was quite lucky actually. One of my other teachers knew one of the leading lithographers in Denmark. His name was Jens Christian Sørensen, and he worked with people as Asger Jorn, Axel Salto, and Henry Heerup. In 1967, he opened Galerie Centre Graphique in Copenhagen, which became a stamping ground for contemporary graphics artists. I became a student of his, and after two years with a progressively rising learning curve, I began to feel the urge to go abroad and see what I could learn within the field around the world. I had had a longing to go abroad since I was young, and my first major journey was to a print shop called Lakeside Studio in Michigan, USA. I worked there for nine months. I started out with lithography but gradually moved on to etchings as my main focus. When I moved to Madrid afterwards, I found a job at a studio called Grupo Quince. I was twenty-two years old and enormously eager to learn, and that stay ended up being a revelation to me because of the generosity and the impressive level of ambition that the three founders of the workshop showed. I arrived at the end of Franco’s rule, Spain was a very isolated country, but Grupo Quince managed to have remarkable international relations, and the three founders, among others María Corral, who later became curator at the Reina Sofia museum in Madrid, established themselves as central figures on the international art scene.

Sometime during 1975, I reached a state in my expatriate existence, where I wanted something new to happen. I had been working with prints since I was quite young, and despite my continuous fascination with the merging of the intellectual and psychical world through print making, I longed for a higher degree of intellectual stimulus. So, in 1977 I returned to Denmark, where I began short-lived studies of economics, which I after a year exchange with film studies, while I worked part-time as a printer at Galerie Edeling under Ivan Edeling.

It was an exciting time with a carefree atmosphere, and one night, when I participated in an event at one of the few galleries from the then modest art scene, I was asked why I did not set up my own studio. Until then, I had found great satisfaction in being tied to a studio and doing my own things on the side, but that night, I felt that my reasons for preferring that situation no longer sounded as convincing as they used to. I now had a deep understanding of print making, and I wanted to apply those skills in a new way. It was a Friday night, and the following Monday I told Ivan that I wanted to start my own studio. Half a year later, I opened up the doors to the place for the first time.

What was the scene of printmaking like in the year of 1979?

When my interest in print making began to develop, it was tradition, that the artists produced most of the prints themselves, back then there were only a few publishers. A change happened in me when I got to USA in 1973-74, where the revolution in printmaking had happened already with influence from Pop Art. With pioneers such as Andy Warhol and Jasper Johns, a new line of thinking developed around what print making was and what it could be. That was a revelation to me. Now, a print was seen as a medium with unique qualities like all other artistic media. Besides that, prints were now more often than not produced in a collaboration between an artist and a printer.

This meant that the artists, who did not necessarily know the techniques, could realize their artistic idea in collaboration with a printer, who had both the equipment and the know-how. Right from the start, I introduced the American model in the studio with the classic etching-techniques and an often long-lasting collaborations with the artists. One of the initial ones was Per Kirkeby, whom I still have a close relationship with today.

As a discipline, printmaking is both an aesthetic and a scientific exploration, an intellectual and a physical craft. What do you think are the core elements of a ‘strong’ print?

A strong print is all about the artist. I truly realized that when I, at an exhibition in Munich that attempted to reproduce Adolf Hitler’s exhibition ‘Entartete Kunst’, saw a tiny etching by Paul Klee. It was horrendously executed with regards to technique, but it is still by far the strongest work in the large room. In other words, technique is not necessarily crucial. A quality print is done by an artist with something to say and who manages to express this through the available media. The German expressionists, for example, were not characterized by a sophisticated technique, but they embraced printing as an equal part of their oeuvre, and that became an important part of the art of the time. Baselitz once said, “talent is an obstacle – it seduces”. I find that to be an interesting way to view print making – as work that stems from a series of obstacles.

You have a particular weakness for photogravure. What makes this technique special to you?

Photogravure appeared in the late eighties where there was a shift in the art scene. The art academies embraced the photo medium in a very broad sense, while sculptures and paintings slipped into the background. As a result of this, I began looking for a way to bring photos onto copper press. Otherwise, we would forget an entire generation. I read up on heliogravure (the classic form of photogravure), which is a highly complex technique, and I made some attempts with photo etching (which produces a very flat grayscale), but it was not until the nineties that I developed a successful technique, learning from Eli Ponsaing, associate professor at Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademi (The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts) and pioneer in the field of photogravure. Since then, we have experimented in the studio with extreme projects, for example by introducing colour printing and doing giant, large-scale formats.

In 1999, you opened the doors to a gallery at Lindenstrasse in Berlin. What motivated you to do this and how do the two locations differentiate?

In 1992, I visited ArtCologne and during that stay, I visited the alternative art fair Unfair, which took place in some industrials halls on the outskirts of town. I contacted the gallerist Bruno Brunnet, who at the time had a gallery in Berlin, and we started a collaboration based on printmaking with a group of selected artists. The process lasted a couple of years, and during those years, I visited Berlin quite a lot. Berlin was, at the time, trying to reinvent itself after the fall of the Berlin Wall. I started playing with the idea of establishing a proofing studio in Berlin, where I could meet artists and initiate the creative process. It quickly dawned on me that an exhibition space would be a better option. A place where we could show the result of the many collaborations. So, in 1999 we opened up the doors to the gallery, which until 2013 were run by Isabelle du Moulin. Today, Tobias Birr is in charge of the daily operations while Lone Weigelt manages the overall business from the studio in Copenhagen. It is a window out into the world in one of the world’s leading art metropoles, and this has resulted in the situation where knowledge of our work has spread across several borders.

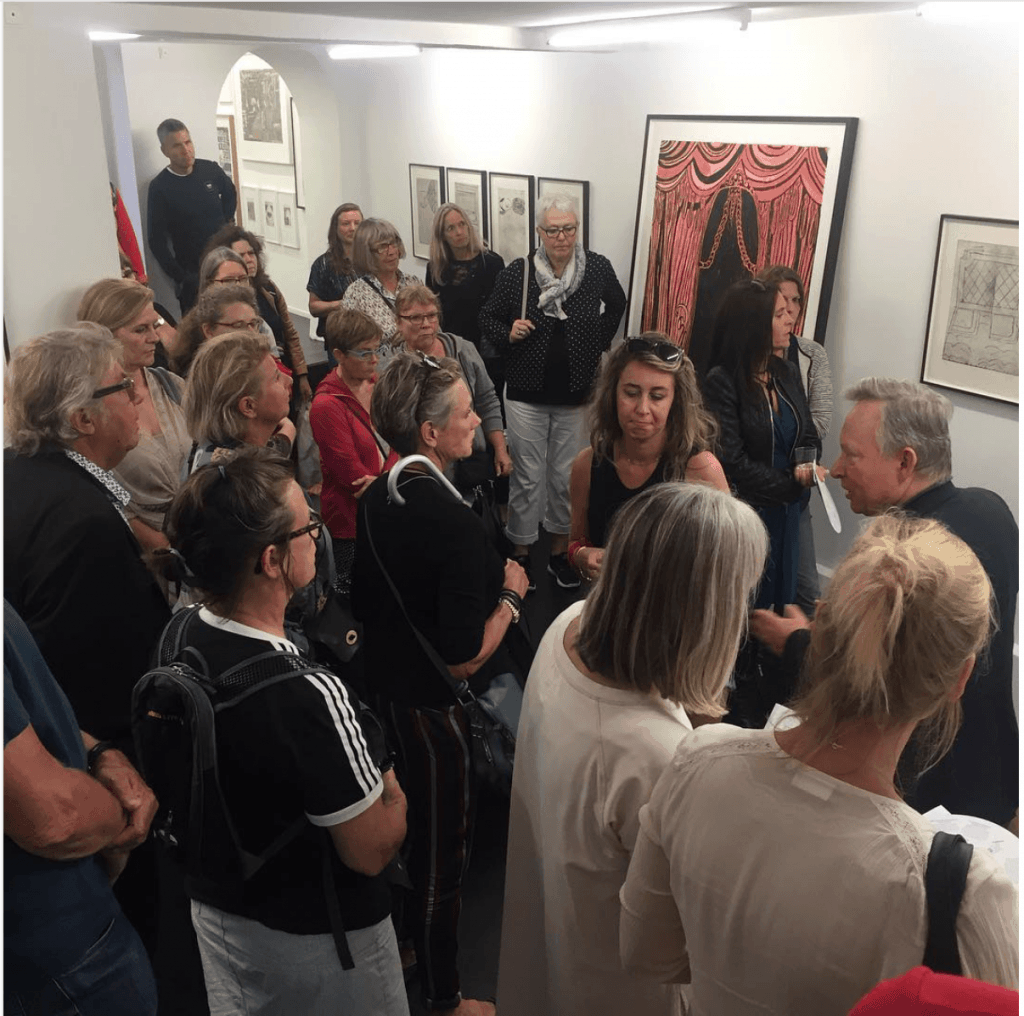

The Copenhagen exhibition space BORCHs Butik opened in the centre of Copenhagen in 2014. How does the two Copenhagen locations supplement each other?

When Lone Weigelt was employed as director in 2012, we began considering expanding our activities in Denmark, where we had been relatively invisible. When the opportunity of renting the space in Bredgade arose, we accepted. BORCHs Butik is intended as an exhibition space at eye level with a larger audience. Because of this, the prints we show there are relatively cheap for the most part, often less than € 1000.

Your projects are included in leading international collections, among others the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art (New York), Statens Museum for Kunst (Copenhagen), and Staatliche Museen zu Berlin. What role does this kind of acknowledgement play to you?

The opening of the gallery in Berlin was the beginning of quite a few things. We established a more direct relation to the artists, which quickly bore fruit. The role of the city as an art metropolis has had a major impact on our expansion of the business. Our exhibition at Art Basel in 2004 was another major leap forward. We were exposed to an enormous audience. Since then, I was chosen as art advisor to the committee for the Editions sector and that meant that our work received recognition from the world’s leading art fair. It has been a slow process, and it would not have been possible without a group of artists with great curiosity and a wish to examine and play with the medium.

You have established yourself as one of the world’s leading producers and publishers of graphic art. What makes you stand out?

An important factor is that we have kept developing our technical abilities throughout the years, just like we began creating our own varnishes in the late eighties, which we in recent years have begun reproducing and further developing. It really comes down to working hard and never losing your curiosity.

Finally, do you collect fine art prints yourself?

I have always taken great honour in not being a collector. To me, it is important to focus on what is in front of me and examine the nature of the medium instead of having an opinion on what art is good and what is bad. That opinion have changed a bit over the last couple of years though. Among other things because of my wife, who is a collector. Because of her, I have begun taking an interest in that world, and I have gotten myself a few works by artists who inspire me and bring new elements into my field of interest, which I always try to develop. Curiosity is my motivational force, and it is what has lead me through the intricate ways of printmaking for almost forty years.