Articles and Features

Portraits of America: Keith Haring’s Crack is Wack Mural

By Shira Wolfe

“[I]nspired by Benny, and appalled by what was happening in the country, but especially New York, and seeing the slow reaction (as usual) of the government to respond, I decided I had to do an anti-crack painting.” – Keith Haring as quoted by the New York Historical Society

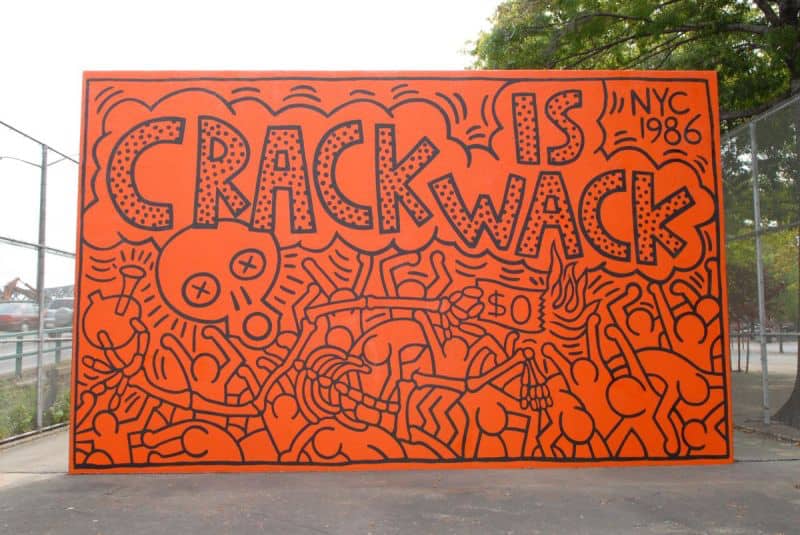

Artland’s “Portraits of America” series explores iconic twentieth century artworks which each in their own way show the many faces of America. This week, as the concluding edition of the series, we feature Keith Haring’s Crack is Wack mural. First painted on a Harlem handball court in 1986, it is one of New York City’s most famous murals. Restored just last year, it’s as inspiring as ever.

Keith Haring

Born on May 4, 1958 in Reading, Pennsylvania, Keith Haring moved to New York in 1978 to study at the School of Visual Arts and attained notoriety in the early 1980s by making his mark on the city with graffiti tags: chalk outlines of interlocking bodies on the black poster mounts in the New York City subways. His images and symbols, such as the radiant child and the barking dog, quickly became easily recognisable. Following public recognition, Haring started to create larger-scale murals, often addressing political and societal themes through his personal iconography; but also supporting social causes in practical ways. He produced colouring books and t-shirts for children, and opened his Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in 1986 where he sold souvenirs of his art, the proceeds of which helped finance “Learning Through Art” and “Doing Art Together”, two charities he set up which brought art to schools. He also provided funds for various children’s organizations, supported anti-apartheid efforts, and financed AIDS research.

Haring died of AIDS-related complications in 1990, at the age of 31. His Crack is Wack mural is one of the lasting public reminders of Haring’s art, vision and activism.

The Crack is Wack Mural

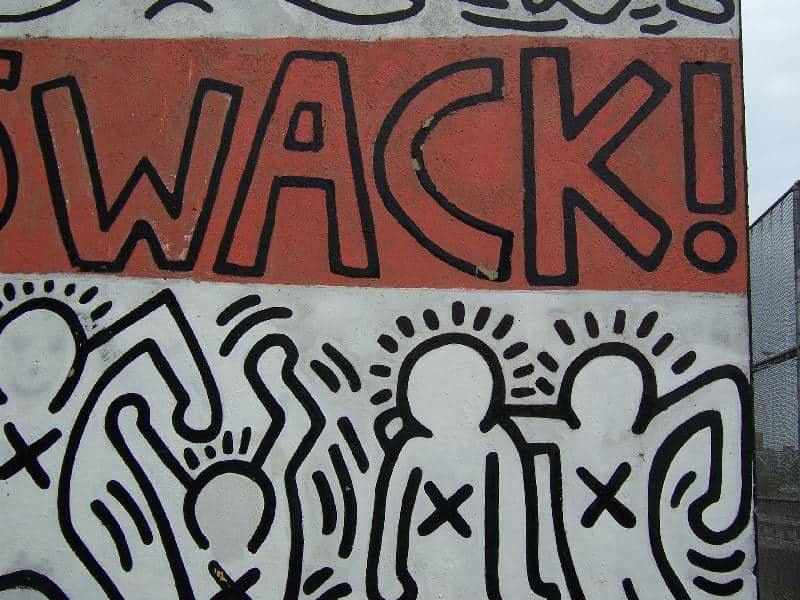

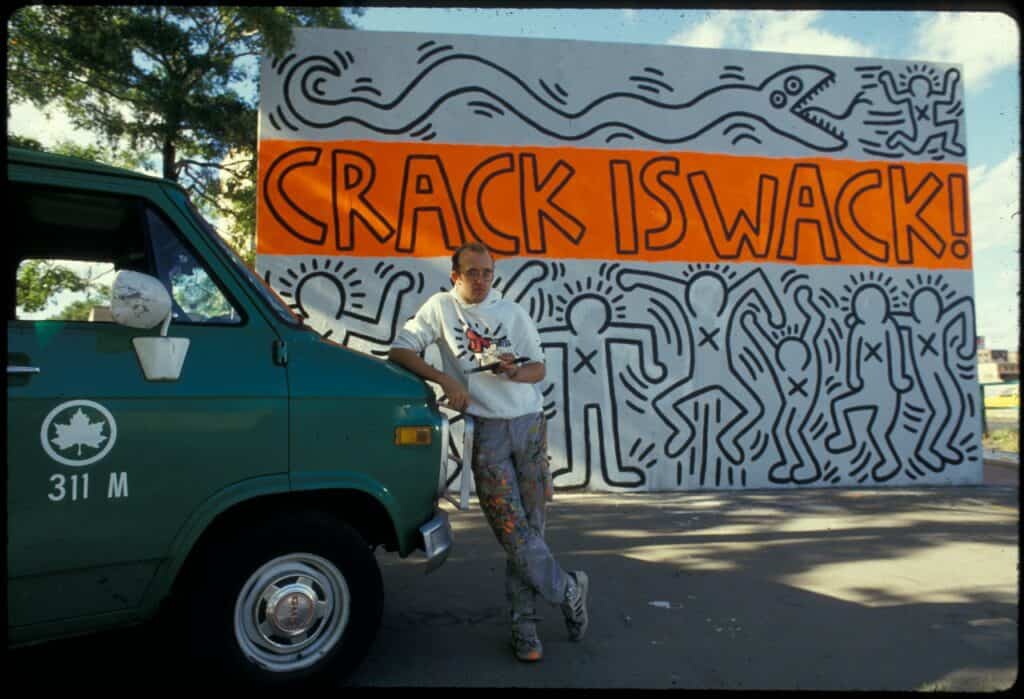

Haring painted the Crack is Wack mural because his young studio assistant Benny became addicted to crack. After many failed attempts to help him kick his addiction, the artist decided to paint this mural in an abandoned handball court near Harlem River Drive, which he often drove past. In painting the mural, Haring addressed his frustrations with the ineffective government on tackling drug-related issues, and his concern with the rising number of crack-addicts throughout the country, and especially in New York City. In the summer of 1986, without any legal permission, Haring set to work. He finished the painting in one day, but just as he and his team were wrapping up, a policeman stopped them and arrested Haring for vandalism. However, the mural and the artist’s arrest quickly received widespread attention and he was released with just a $100 fine to pay.

Not long after, the mural was defaced by a vandal, who turned it into a pro-crack mural. Someone from the Parks Department then took it upon themselves to quickly repaint the mural a drab grey. Fortunately the Parks Department commissioner reached out to Haring and asked him if he would repaint his mural, which by that point had already become important to and beloved by the public. Haring agreed, this time producing a two-sided mural with his anti-crack message vibrating off both sides of the handball court wall. According to Gil Vazquez, the acting director and president of the Keith Haring Foundation, it wasn’t like Haring to recreate the same thing twice, underscoring how important it was for him to get this message across.

“Keith Haring did a lot for the community, and it’s really nice to bring his legacy back through his art.” – Louise Hunnicutt

Restoration of the Crack is Wack Mural

The mural remained in place as a bright warning for the neighbourhood, but suffered from natural deterioration over the years. It underwent multiple restorations, but most of them were fairly superficial until recently. It was restored in 2019 by artist Louise Hunnicutt, with support of the Keith Haring Foundation, following the recommendation of the New Museum. “Keith Haring did a lot for the community, and it’s really nice to bring his legacy back through his art,” said Hunnicutt. She describes how lots of people were excited seeing the restored mural, remembering it from when they were kids.

To fix the severe water damage to the surface, Hunnicutt and her assistant William Tibbals peeled off the remainders of past restoration jobs and coated the walls with waterproofing, concrete, and acrylic mixed with hardener, and secured what was left of Haring’s original brushstrokes. They then created stencils of Haring’s designs using tracings that they developed from the original image and photographs. The entire restoration process took 648 hours, while it took Haring just one day to paint.

Today, it can be appreciated again in its vibrant original form at E 128 St, 2 Ave & Harlem River Drive.