An interview with Mikkel Carl

The artist, writer, and freelance curator Mikkel Carl has become somewhat of a brand on the contemporary art scene. With a BA in continental philosophy, it wasn’t in the cards, but as one of his recent works Pick a Card Any Card, 2018 reveals (upon purchase buyers will draw a gold-plated playing card at random), it is not obvious how life turns out. This is the story of a Danish multitasker and the accumulation of activities that ended up constituting a brand: Mikkel Carl.

It all started in 1976; the year Steve Jobs founded Apple, Fidel Castro became President of Cuba, and Mikkel Carl was born. From here onwards, we follow the making of a brand, decade by decade, up until today, where Mikkel Carl finds himself at a crossroads. Ties have been severed and new ones are being formed in his ongoing investigation of art as a prism to perceive the world, be it from an artistic, critical or curatorial point of view.

1976

When PS1, the contemporary art center in Long Island City, New York, later known as MoMA PS1, opened in 1976, a new vital resource of art came into being. You were born in the same year. Can you recall any moments with art from your early childhood?

Well, does usurping your little sister’s Disney colouring book to practice staying within the lines count? In general I have a disquieting lack of memories, and unless it’s because The Tyrell Corporation went soft on the implants – I guess it’s because my mental capacity is fully occupied with analyzing the present and projecting what things could be like in the future instead of dwelling on what they might have been like in the past. But I vividly recall said ambition to colour all the drawings in perfect concordance with how the Disney characters really look thereby turning my painting book into something resembling a cartoon.

I also played a lot with LEGO. Every Saturday and Sunday morning before my parents got up and we would have breakfast together. I would either built a fire station strictly according to the designated schematics – I do remember the unsettling feeling when I discovered the alternate versions in the back of the manual – or I used all the Lego bricks to build something according to my own design. This included a “sound system” with a double cassette deck, an LP player and (drum roll): a CD player.

For many years I was also a boy scout, which was at the time, and I guess it still is, something very uncool. Nevertheless, activities included among many other things making a layer cake at 4 am on some deserted, suburban street, having been sleep deprived for days. Have you ever tried making whipped cream with a stick? Besides taste, we received points for both aesthetics and our ability to corporate within the group. As it turned out, I’m not much of a team player. I simply prefer doing everything myself in order to secure a homogeneous “product line”. Unfortunately, this is now beginning to create bottlenecks.

1986

In 1986, Andy Warhol made his last self-portrait. If any, he was an artist who created a distinctive brand around his persona, becoming synonymous with the Pop art movement. As a 10-year-old boy growing up in the 80s, you perhaps had not come across Mr. Warhol just yet. However, my research tells me that you were obsessed with brands in your early teens. Can you elaborate a bit on that? Did it influence you later on?

It’s true. From very early on I was exceedingly interested in clothes and brands, even though most of my friends weren’t. Coming from a lower middle-class background I couldn’t afford to buy brand clothes, so it was a big thing to me when my uncle returning from a position in Thailand brought back embroidered Lacoste-crocodiles in bulk. I had my mother sew one on to my home knit sweater. I also talked my grandmother into stitching all kinds of patches onto my brand new jeans – my mother did not appreciate the gesture. I also recall a particular fight I had with my parents because I wanted to wear a tracksuit with my Nike socks, which actually consisted only of the top part featuring the logo that I had cut of a worn out pair, on the outside of the pants. It was my paternal grandmother’s 70-year birthday dinner in the knight’s hall at a local castle, so I didn’t win. In my room, the walls were covered not by rock star posters or autographed pictures of soccer players but with homemade Nike Air Jordan advertisements. I also remember being utterly amazed when my math teacher told us that Japan exported pencils labeled “P.arker” instead of “Parker.”

Later, I went on to making my own “Levi’s” T-shirts using the textile pencils I got for my birthday. I still recall one that I was particularly proud of: Having learned this trick as a boy scout deciphering hidden messages I sprayed lemon juice on to the soles of my worn Timberland booths, walked across a piece of paper, and then gently heated it from below until the footprints appeared. These I traced on to the T-shirt adding the Levi’s brand and a text saying: “Rebels never go out of style, they just walk away.”

I did manage to sell one copy, but sadly my pens were in fact not washable, so I had to return the money. And a lot of the time I just felt bad due to the fact that my brand clothes weren’t genuine and because I sucked at freehand drawing. This feeling sort of stayed with me until I, many years later discovered appropriation art stumbling upon the catalogue from Jeff Koons’ exhibition at Aarhus Kunstmuseum. Mind you, the only art exhibitions I ever saw as an adolescent were Monet and Asger Jorn at Lousiana plus a show during Easter at my public school were my math teacher exhibited his amateur photographs.

1996

The next decade in your life marked your entry into the education system. You have a BA. in History of Ideas (1998-2002) and an MA from The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (2003-2009). Can you tell us about this move towards an artistic practice?

In high school my elective course was psychology, which was a great disappointment to me, so right after graduation, I took an evening class course in philosophy. The students were mainly middle-aged nurses and disability pensioners, but the teacher was extremely dedicated. She had published a couple of books herself, and when graduating from this course, I was examined in Baudrillard’s concept of simulacrum. I believe this is the only straight A I have ever got, and my teacher recommended that I went to a folk school called Testrup Højskole focusing on philosophy. Please note that this was the late nineties, the heydays of existential self-indulgence post cold war and before 9/11.

In 1998 I matriculated at History of Ideas, which is basically continental philosophy, and it was phenomenal. I wrote lengthy, highbrow essays though because I insisted on using a self-invented system of parentheses á la Derrida, enabling sentences to be read in at least three different ways, my grades were not that phenomenal.

In one of my classes was this older guy who had been a teacher at the local art academy prep school, and when he realized I shared his interest in the dialectics of art and philosophy, he urged me to take a leave of absence. For some reason I insisted on finishing my BA (it took me four years), but when I finally sat down in sculpture class with a worktable full of stuff something did happen. Fortunately, I was accepted straight away into the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts (and also the local Jutland Art Academy) because if I hadn’t been, I’m not sure I would have had the guts to pursue it any further.

2006

During the summer of 2006, the Museum of Modern Art in New York did a major show on Dadaism. The exhibition, which premiered at the National Gallery of Art, was the first in the United States to focus exclusively on Dadaism, one of the 20th century’s most influential avant-garde art movements. In your practice, you show a continuing interest in ‘found’ objects, which have an affinity with Dadaist ready-mades as well as postmodernism’s strategies of appropriation. Why are you drawn to this interventional approach and how do you experience the traces of the past as a way to create new meaning?

In my first year studying History of Ideas, I read both Ursprung des Kunstwerkes by Martin Heidegger and T. W. Adorno’s Ästhetische Theorie, both dealing with the metaphysical and socio-political aspects of art. Popular at the time was also a notion of “aesthetic experience” not being limited to artworks per se but rather used in the attempt to conceptualize a general aesthetic dimension by drawing heavily on romantic philosophy and literary theory. Personally, I found all of this a little too romantic, but then I started reading and writing about the readymade strategy combining it with my interest in post-structuralism, which is the best excuse ever for not being original. My main concern was to trace a common productive force that cannot be conceptualized in and by itself, but only retrospectively through the difference between the entities “it” creates. The point is that it is not the things in themselves but the differentiating principle that is in a way original. Cut down to basics, in my opinion, this is what Jacques Lacan calls ‘lack’ or ‘absence,’ Michel Foucault names ‘power,’ Roland Barthes generalizes as ‘writing,’ and Jacques Derrida even makes up a new word for, namely ’différance.’

This enables us to see the unrealized potential in the readymade strategy. Most often the avant-garde has been identified with the Hegelian ideal of overcoming the distinction between art and life. Most famous is Peter Bürger’s Kritik der Avantgarde, in which he describes the neo-avant-garde of the sixties as merely the institutionalized version of the historical avant-garde thus making it clear how unsuccessful its attempt to repeal the category of the artwork was. Personally, I regard this outspoken ambition as more of a rhetorical tool trying to create a movement towards something new. After all, it was indeed a crucial moment in art history when everything no longer had to be created from scratch (pigment and media, clay and plaster, the raw marble block). The ready-made was and still is a far more realistic way for art and life to come together.

Inspired by Freud’s concept of ‘Nachträglichkeit,’ meaning ‘postponement’ or ‘delay,’ as well as the notion of ‘différance’ – a trace left without an original – Hal Foster claims that the past never ends. Whatever happens, will keep affecting what once happened. Had the neo avant-garde not taken up the strategies from Dada, Constructivism, Futurism, and Surrealism, there would never have been a historical avant-garde. It was the repetition that created the original movement.

You once said in an interview that “whether it’s painting, drawing, photography, sculpture or even installation art it is expected that a moment of truth will occur in the contemplation of the work.” What do you mean by truth?

Theorizing the avant-garde in the way I just did offers a peculiar mixture of linear and cyclic time, which means that as an artist you can keep creating new meaning even though everything has already been done several times over. But of course, there’s also a downside to all of this. With any “negative” philosophy – be it Adorno’s negative dialectics or Derrida’s deconstruction – the problem is that you stay fixed on whatever it is you’re trying to surpass.

2016

2016 was a busy year. You had a residency at the International Studio & Curatorial Program (ISCP) in New York, you became a member of the Danish Arts Foundation’s Committee of Visual Arts Grants Funding (2016-2019) appointed by the Minister of Culture, and you helped start Code Art Fair – among many other things. How do you manage to navigate between your different roles? Do you think they complement each other, or do you sometimes experience a downside?

Around this time last year – right after the names of the recipients of the Danish Arts Foundation work grants were made public – I was quite viciously attacked by an artist aided and abetted by Radio 24syv and later on Berlingske. Somewhat in the style of Hans Hacke said artist made me the ground zero of his investigations into the supposedly dirty power play of the Danish art scene. So, I guess if you ask him, I do not navigate these shark-filled waters very well. Obviously, I do not agree. Not only, am I not corrupt, I honestly believe I bring something new to the table using my capacity for (post)structural analytical thinking to combine things traditionally thought of as separate entities. For one thing, the board has to some extent regained an international focus, which is absolutely necessary since a lot of our most talented young artist are now trained abroad, and they often tend to stay and show outside of Denmark because they are not properly welcomed back.

Recently I gave a talk about my experience with ISCP, and for some reason, I didn’t quite consider whom the audience was, namely people who all produce international residencies. So, after less than five minutes people started shouting at me: “This is ridiculous!” But you know what I find ridiculous? To lure upcoming artists of all ages plus their patrons into paying all this money for a bunch of prepackaged studio-visits, and a “stimulating environment”, which owes most of its grandeur to the city where the program is located. As most artists won’t speak up, for obvious reasons they don’t want to seem ungracious, I hereby urge the Danish Arts Foundation to take this whole system under consideration. As an alternative, I advocate an individualized host/hostess model, where a studio apartment is given to two artists at a time, and then there is someone on the ground, paid to personally introduce the artists to designated actors on the local art scene.

And yes, then there is Code art fair, which against all odds, is in its third year. Again, let me use this opportunity to urge all Danish artists to come have a look no matter their stand on “the commercial” part of the art scene. It’s really a sight for sore eyes wondering about galleries like König, Nagel-Draxler, and Perrotin when only 5 years ago all we had was Art Copenhagen in Forum. We really can’t thank Bo, Susanne, Jesper, Claus, and David enough for taking the reins and creating Chart, setting off somewhat of a chain-reaction so we now have two interesting fairs in Copenhagen rather than none.

You have been working as an art critic alongside your practice as an artist. What does art criticism mean to you, as a critic and an artist?

Authoritative readings of my work are what I desire more than anything; it is my Lacanian lack impossible of fulfillment. My father died from cancer nearly 20 years ago, and when he was around, I did everything in my power to “kill him”. This is textbook Oedipus: I actually won, but now I will forever desire his praise. As sort of a coping mechanism, I started to acknowledging other artists work curating shows and doing lengthy interviews such as this one. And as of late – writing the grounds that accompany the cash awards we in The Danish Arts Foundation give to extraordinary exhibitions – I seem to have found my preferred genre: The overtly positive “review.”

Artist, “critic,” and curator… Do you also collect art, and if so, identify yourself as a collector?

I’m definitely not a collector. My own artistic praxis entails so much logistics that I have no intention of managing an extensive art collection on the side. But as it is the case with most of my peers, supply often exceeds demand, at least to some degree, and instead of wasting precious space storing older works, we swap. That is what you call a win-win situation, and so maybe one day I will get my own profile on Artland.

In 2016, you created the work Britney Survived 2007 – You Can Handle Today, made out of “an equal amount” of US cents mounted on a milled steel sheet and Eurocents mounted on an anodized aluminum sheet – commenting on the exchange rate fluctuations following the American presidential election. Would it be correct to say that your conceptual works often constitute a dialogue between various cultural references via both language and materiality, thus inviting the viewer into a semiotic space, where she can build upon hitherto fixed meanings to ultimately create new ones?

Yes.

Do you believe that art can help us handle challenging times?

No.

2018. To infinity and beyond…It is time to take stock of the brand Mikkel Carl. You have recently terminated a yearlong collaboration with the Copenhagen-based gallery Last Resort. What was your reason for this and what is your next ‘resort’?

In any relationship, be it romantic or otherwise, you can simply outgrow each other. For a long period of time you struggle to make it work, and when it doesn’t hopefully you go your separate ways – with no hard feelings. As for the second part of your question, eventually I will of course be looking for a serious relationship, but right now I’m satisfied with a little bit of Island-hopping.

This spring, you curated the exhibition Pizza Is God in a museum in Düsseldorf featuring such prominent artists as Martin Kipperberger, John Baldasarri, John Boch, Reena Spaulings and many others. Can you tell us a little about this exhibition dedicated to the pop phenomenon of pizza?

In general, my curatorial projects each revolve around one basic idea, acting as sort of a common denominator that allows me to juxtapose conceptually intricate works and to address complex cultural orders via a thematic framework more or less immediately comprehensible to the public. Pizza is God was a good example of that, since everybody loves pizza, but for very different reasons.

In a way, a pizza is like a painting. The dough is the stretched canvas, and all the different kind of toppings describes a mix between figuration and abstract composition. And then once the cheese melts, the pizza becomes more of a glazed bas-relief. As a cultural phenomena pizza is both social, you can share it, and highly individualizing. Show me your pizza and I will tell you who you are. Rye sourdough with vegan meatballs, or cheese stuffed-crust, deep pan pepperoni…

How did you get the idea for the show?

It actually started out as an artwork of sorts. I was invited to this digital biennale and I was going to create a database with all the artworks I could find dealing with pizza. But not being a digital native myself, as my research came along I realized how much I wanted to see some of these amazing works IRL, e.g. Tom Friedman’s “family pizza” with a diameter of almost 2 meters. And I honestly thought that a pizza exhibition would be a museum “no-brainer”, but strangely enough nobody wanted to do it. So, I put the project to rest, until much later, I was contacted and asked if I wanted to do the show at NRW-Forum in Düsseldorf.

“We are already starting to witness visionary acts of digital curating, and curating will surely change as a generation native to digital tools begins to develop new formats. This generation has grown up in an entirely new world. Perhaps by learning from them, we can learn something about our future” – a quote from the book ‘Ways of Curating” (2014) by Hans Ulrich Obrist. How do you see this brave new world? How important was it to you to incorporate technology and the digital layer of contemporary life into the making of the brand Mikkel Carl?

For a long time, I thought I was using social media to my advantage, posting all the right stuff: process images from the studio, videos of our cat, pictures of all my Nike shoes…as you say slowly building the brand Mikkel Carl, giving my (somewhat limited number of) followers a sense of my unique experience of the world. And maybe I was, but the price was steep. I spent way too much time and energy worrying about what other people may think about my work. I mean, of course, everybody cares how many likes they get, but when the depicted artwork is something you just made, it can be devastating to get too few – whatever that means. So, for more than 3 months I have been in “rehab”, and only recently did I post a few images relating to my solo shows at M23 Projects in New York, and Galleri Jacob Bjørn in Aarhus. I guess the temptation was too great, but I swear, I won’t make another post until I feel significantly different about the whole thing. Riffing off some new works called Untitled (Glamour Is for Those Who Can Afford not to Be Glamorous) I believe social media is mainly for those who can afford not to be on social media.

Does this add a more personal dimension to the overtly critical Terrified of Society and Its Unclean Bite, which is the title of your New York exhibition?

I don’t know, but my wife said the very same thing. As for the obvious Trump-bashing please allow me to quote from the excellent exhibition text written by Jeppe Ugelvig, a Danish curator and art critic just now graduating from Bard College:

“The monolithic work specific to M23’s Morgan Avenue project room consists of a 12 foot, faux reinforced concrete wall built inside the gallery space, effectively bifurcating it in two. By rendering one side inaccessible to the viewer, Carl produces a spatial self-awareness in the spirit of classical minimalist sculpture. The piece can also be understood to reference the Berlin Wall, as well as Richard Serra’s controversial 1981 public sculpture Tilted Arc, both by-gone monumental architectures. Shared amongst these projects is a very direct attempt of controlling and commenting on space and its politics through analog and architectural means loaded with heavy-handed symbolism—as recently encapsulated by the border wall proposed to separate Mexico from the United States. Thus, perhaps a more immediately congenial source of inspiration is Michael Asher’s 1974 removal of the partition wall that separated the office space from the exhibition space at Claire S. Copley Gallery in Los Angeles. On two previous occasions, Carl has engaged this work by partly tearing down partition walls he had built in existing door openings between exhibition spaces, giving the viewer a false sense of something hidden now being exposed (A Thing Is a Whole In the Thing It Is Not, 2012/2015). More recently, the artist covered existing exhibition architecture at ARoS with variously colored wall elements from previous exhibition designs, while also leaving behind the install crew’s paint-splattered Bauhausian folding chairs (What Cannot Be Imagined Cannot Be Seen, 2015/2017).

Is something similar at stake in your show at Jacob Bjørn, a gallery also located in Aarhus?

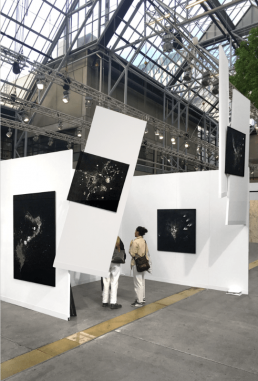

The main installation consists of 6 individual faux steel plates each measuring 5 x 122 x 305 cm. They may be combined in any number of ways depending on the exhibition context; e.g. as an upright wall bifurcating the gallery, as it did at Last Resort, or perhaps a narrow passage like in the tiny cph_kabinet. This time the work has been adapted to a high-ceilinged gallery space located in the defunct Ceres brewery, where it will partially obstruct an unusually high sitting suite of windows. The exhibition is called Panem et Circenses, which is Latin for “bread and games”. I figure the raw “steal” plates are the food and the new series of “paintings” as the entertainment. These superficial means of public appeasement are made from purposefully damaged gold metal foil applied to aluminum stretchers, mirroring their surroundings in a stimulating, busted fashion — including the visitors themselves. They come from a public work I did last year at Sydhavn Station installing self-adhesive mirror foil on poster stands, instigating a moment of reflection in bypassing commuters in the place of conventional advertising. But emphatically re-entering a commercial context, I invert the original reflectivity of the public work and to some degree render it a hollowed, commoditized experience, radically questioning the supposed sincerity of any artistic gesture, my own included.

In light of this, how is the show doing from a commercial point of view?

Surprisingly well, actually. It almost sold out on the night of the opening, including the centerpiece A Vague Nothing at the Intersection of Subject and Object (2017), which was acquired by ARoS – Aarhus Art Museum.

Try and think five years ahead…where do you see Mikkel Carl?

It’s funny, even though I think ahead all the time I have never done that exactly, but here we go: Not to become too dependant on sales, I find it essential to have some sort of basic income, and considering I have been teaching on and off since I was in my second year at the art academy I believe I would make a decent professor at a regional art academy. Hopefully, at some point I will also receive a commission for a permanent public artwork – this is something I’m dying to try and get my hands on. Furthermore, I hope to find a new gallery in Copenhagen and possibly one abroad. And fingers crossed maybe some larger institutions will begin to show interest because as an installation artist there is only so much you can do within a commercial context. In fact, I’m perfectly happy if things gradually evolve, as they have been ever since I graduated nearly ten years ago. Each year I have been able to do stuff, I couldn’t have done the year before, or the year before that.

Stay updated on the latest ‘brand’ news here.

Get your free copy of Artland Magazine

More than 60 pages interviews with insightful collectors.