Articles and Features

Stories of Iconic Artworks: Picasso’s Guernica

By Shira Wolfe

In occupied Paris, a Gestapo officer who had barged into Picasso’s apartment pointed at a photo of Guernica, asking: “Did you do that?” “No,” Picasso replied, “you did.”

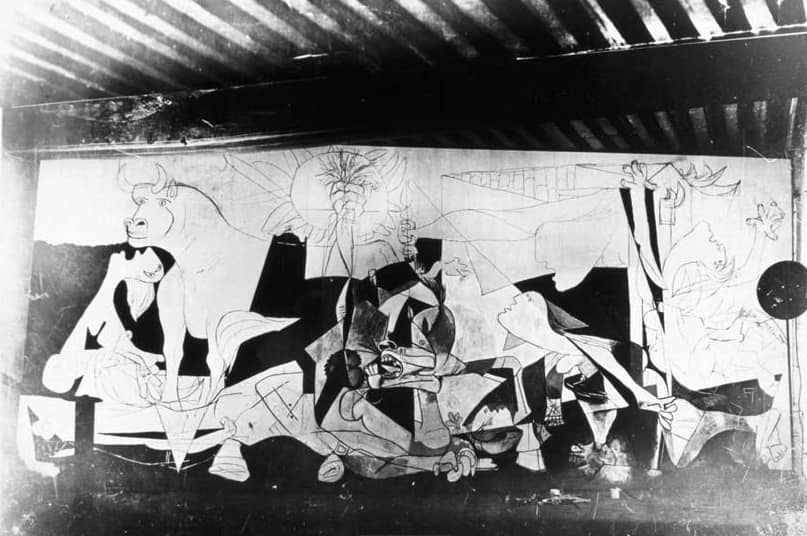

We take a look at the painting that is considered one of the most emblematic of twentieth-century art and modern history: Guernica by Pablo Picasso. An iconic and touching political statement, this large-format oil painting has become an emblem of the protest against the horrors of war. We explore the historical circumstances that led to its creation and the events that followed.

The Bombing of Guernica and the Commission

On 26 April 1937, at the very height of the Spanish Civil War, German and Italian armies bombed the Basque city of Guernica. It was a show of support for the nationalist forces which were fighting against the government of the Second Republic. As the first place in Spain’s Basque region where democracy had been established, Guernica was a symbolic target. Hundreds of civilians were killed and this marked the first instance in which a defenceless city was attacked during the Spanish Civil War. At the beginning of that same year, Pablo Picasso, who was already living in Paris, had been commissioned by the legitimate government of the Republic to produce a large-scale, mural-sized painting for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair that summer.

But just two months before the show, in April 1937, Picasso found himself in the midst of a personal and creative crisis. He had no idea what to produce for the commission and had been toying around with female nudes. Then, on 26 April, the attack on Guernica happened. When the news reached Picasso, he started working feverishly on the large canvas that was to become one of his most iconic pieces: Guernica.

The muted colours, the intensity of each and every one of the motifs and the way they are articulated are all essential to the extreme tragedy of the scene, which would become the emblem for all the devastating tragedies of modern society.

Paloma Esteban Leal

Creating Guernica

In just a month and a half, Picasso produced approximately 50 sketches and drawings, and also made various modifications to the large canvas. The various stages of the creation of Guernica were captured in photographs taken by Dora Maar, his lover and muse at the time.

The father of Cubism had been deeply moved by the dramatic photographs of the bombing of Guernica, which he had seen in various newspapers. Yet while this attack was the main catalyst for the work, Picasso never once alluded to any one particular moment or event in his sketches or in the final canvas. The painting, instead, was one big cry of protest against the horrors of the Spanish Civil War and a forewarning of what was soon to become the Second World War. Due to the intensity of each suffering character in their muted colours and contorted expressions, Guernica soon became the emblem for all the tragedies of the modern world.

Picasso portrayed a chaotic composition of six human figures, a horse, and a bull, their faces expressing anguish, terror, suffering and grief. Overhead, a lamp bursts with light. While he never wanted to make the symbolism behind each figure and object explicit and preferred to leave it up to the imagination and interpretation of the viewer, the painting’s strong rejection of war and violence is crystal clear. The most direct depiction of desperation can be seen in the contorted expressions of agony in the faces of the women.

The Life and Meaning of Guernica

Since it was first unveiled at the Spanish Pavilion in Paris in 1937, Guernica travelled extensively all throughout Europe and the Americas. During the Second World War, Picasso accepted an invitation from Alfred H. Barr Junior, at the time the director of the MoMA in New York, to leave the painting on loan at the museum and keep it safe from the raging war in Europe. Picasso always did exactly what he wanted to do with the painting: he refused to remove it from the MoMA despite being urged to do so by campaigners against the Vietnam War. He also refused to deliver Guernica to the Spanish Modern Art Museum in 1968, upon Franco’s request. In 1979, he claimed that the painting belonged to the Spanish people and would be brought to Spain once the freedom of the Spanish people had been restored. In 1981, six years after the death of Franco and eight years after the death of Picasso, Guernica finally made its way to Spain, where it is on view at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia.

Imbued with symbolism, the meaning of Guernica as an expression of outrage over the Nazi attack has broadened, becoming synonymous with places all over the world where defenceless civilians have come under attack – in protests against war and senseless violence worldwide, people can be seen carrying Guernica banners. It is a timeless, universal symbol against war and suffering.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn more about Picasso and Guernica:

Museo Reina Sofia

Discover another iconic artworks by Picasso:

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon

Learn about Picasso’s investigation into ceramic production:

Artland Spotlight on: Pablo Picasso’s Ceramics

Explore stunning works by Pablo Picasso available for purchase on Artland:

Buy artworks by Picasso