Articles and Features

Stories of Iconic Artworks:

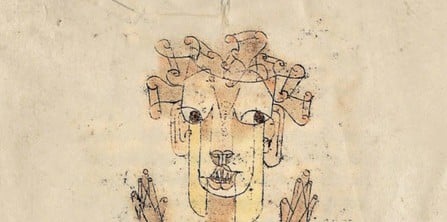

Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus

By Shira Wolfe

“This is how one pictures the Angel of History.” – Walter Benjamin

Angelus Novus, the Paul Klee painting barely known during his life, became Klee’s most famous painting, mostly because of the exceptional story of its connection to German-Jewish philosopher and critic Walter Benjamin. Benjamin purchased Angelus Novus in 1921, frequently referring to the work as his most treasured possession. The angel was to make appearances in Benjamin’s writing until his death in 1940.

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, and Walter Benjamin Meet

Paul Klee was a young artist when he created Angelus Novus, an angel made with Klee’s self-developed oil transfer technique and watercolour on paper in 1920, not long after the end of World War One. During the war, Klee had been conscripted into the German forces, but he spent much of his service away from the front, allowing him to paint and draw. 1920 was a breakthrough year in Klee’s career. He had his first large-scale exhibition in Munich, which included Angelus Novus, was about to join the Weimar Bauhaus, and came up with his artistic credo “Creative Confession,” which encompassed his metaphysical perception of reality.

In the spring of 1921, Walter Benjamin, the philosopher and critic who was already making a name for himself as a heterodox thinker, bought Angelus Novus for 1000 marks, and hung it in his office in Berlin. He was so taken with the painting that he hung it in every apartment he lived in, writing of the eccentric angel hovering as though caught between moving forwards and backwards: “This is how one pictures the angel of history.” Benjamin was not a systematic thinker, but rather used experiment and contradiction to come to his new ideas. Klee, an unconventional modernist who effortlessly moved between Bauhaus and Surrealism, was not unlike him in this. A great deal of Benjamin’s thinking about art, like his conception of “aura,” a numinous quality of art that becomes lost in the process of mechanical reproduction, was informed by Klee’s paintings and drawings, in particular by Angelus Novus.

“But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them.” – Walter Benjamin

The Rise of Nazism

Under the rise of Nazism, Benjamin’s dream of becoming Germany’s leading critic, and Klee’s work as a member of the faculty of the Bauhaus, came under severe threat. Klee was dismissed from his teaching job in 1933 when Hitler rose to power, and moved to Bern, Switzerland. Several of his paintings ended up in the Nazis’ Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937. Benjamin had left Germany right before Hitler’s accession to power, and first went to Spain, then Paris. He had to leave behind his beloved angel painting, but a friend brought it to him in 1935. This was the year the Nuremberg laws were adopted, redefining German citizenship and leaving Benjamin, the Jewish philosopher, a stateless man. When the Second World War broke out, Benjamin began to write “On the Concept of History,” a fragmentary text attempting to make sense of the dark downwards spiral the world was caught in. In this text, the image of Angelus Novus served as Benjamin’s touchstone:

“There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. An angel is depicted there who looks as though he were about to distance himself from something which he is staring at. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth stands open and his wings are outstretched. The Angel of History must look just so. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet. He would like to pause for a moment so fair [verweilen: a reference to Goethe’s Faust], to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the rubble-heap before him grows sky-high. That which we call progress, is this storm.”

In 1940, when France surrendered to the Nazis, it meant imminent disaster for Jewish refugees such as Benjamin, and all the hope he’d had left for his future was shattered. While fleeing from Paris across the Pyrenees, in the hopes of reaching Lisbon and setting sail to New York, Benjamin, fearing capture by the Nazis, swallowed a lethal dose of morphine pills in the Catalan seaside town of Port Bou. His tombstone in Port Bou reads: “There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” Klee died in Switzerland that same year from the disease scleroderma. Inscribed on his tombstone are the words: “I cannot be grasped in the here and now, for my dwelling place is as much among the dead, as the yet unborn, slightly closer to the heart of creation than usual, but still not close enough.”

What Became of Angelus Novus?

The angel, like Benjamin, roamed around like a vagabond for years. Before Benjamin left Paris, he entrusted Angelus Novus and his papers to the author Georges Bataille, who managed to keep them safe in the Bibliothèque Nationale until the liberation. After the war, his possessions were passed on to the Frankfurt School philosopher Theodor Adorno. They later came into the hands of Benjamin’s close friend, the Kabbalist scholar Gershom Scholem in Jerusalem. Finally, in 1987, Angelus Novus ended up at the Israel Museum, gifted by Scholem’s widow.

Today, the angel rarely travels – a 2016 appearance at Centre Pompidou in Paris was one of the rare exceptions – but one need only read Benjamin’s writings on this “Angel of History” to feel as though surrounded by its strange and powerful presence.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about the extraordinary story of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus here: