Cubism

September 1912. Pablo Picasso has just returned to Paris after an intensive working period with Georges Braque in Sorgues. The exchanges between the two artists in this period were later to be described by Braque as ones that ‘nobody but us would ever be able to understand.’ Braque wanders past an Avignon wallpaper store, and spots some wood-grain wallpaper. He immediately goes in to buy it. Back in the studio, he starts pasting rectangular patches onto the surfaces of several large charcoal drawings. The drawings and the paper intersect and interact in a way that will bring a totally new direction to the art of both Braque and Picasso. The tension of the combined tactility and visuality creates a rupture, a jolt. “After having made the first papier collé, I felt a great shock, and it was an even greater shock for Picasso when I showed it to him,” recalls Braque later.

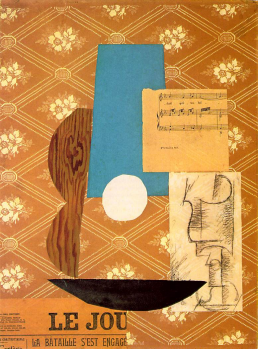

Back in Paris, after having seen Braque’s papier collé (from the French word coller, meaning “to glue”), Picasso immediately embarked on a phase of collage – he created nearly a hundred papiers collés in short succession. In one of Picasso’s earliest collage works, Guitar and Sheet Music, he pasted and layered paper, creating shading and structure. The early collages are also filled with fragments from popular songs, fake wood-grain paper, and snippets of bodies, faces, instruments and other objects. Picasso was in the process of studying and dissecting objects like a surgeon dissecting a corpse.

It didn’t take long before other artists in Paris caught on to this new exciting development that Braque and Picasso were immersed in. The Spanish artist Juan Gris, a deeply committed two-dimensional artist, used collage to continue to develop his two-dimensional art. His papiers collés have been described as some of the most pictorially complex of his time. Futurist artists quickly took over the collage style as well. In the art of Boccioni, it became a method of enriching the surface, while Carrà included ready-made elements in his ‘free word’ pictures. Then there was Balla, who used collage to craft visually mobile versions of three-dimensional constructions.

Constructivism and Suprematism

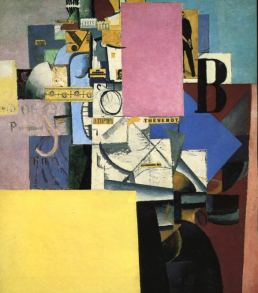

In Russia too, the art scene was buzzing with talk of Picasso and Braque’s collages. Here, significantly, the revolutionary experiments undertaken in art were a collaboration between writers and visual artists. The word was the primary terrain of exploration, and was an important element in the collage work of the artists. Malevich’s Woman at a Poster Column from 1914 uses collage elements to shift the coordinates of the image. Various words find their way into the painting, later referred to by Malevich as “phonic masses.” He wrote the following about these phonic masses: “We can tear the letter from its line… give it the possibility of free movement. Lines suit only the world of bureaucracy and domestic correspondence… We came to the distribution of letter-sounds in space, just like Suprematism in painting. These phonic masses will be suspended in space and will produce for our consciousness the possibility of reaching even further from Earth.”

DADA

The political madness of the First World War produced DADA. Stylistically, in their combinatory methods of pasted paper, the Dadaists shared many similarities with the Cubists. Hans Arp, for one, had come to Paris in 1914 to avoid the military draft in Germany and must have seen Picasso and Braque’s papier collés there. By November 1915, Arp had fled Paris to neutral Zurich and was exhibiting collage works at Gallerie Tanner. In the catalogue, he explained that the works were “structures of lines, forms and colours that attempt to achieve the infinite and the eternal – beyond the human realm. They are a denial of human egotism.” A significant contribution was made by Kurt Schwitters, who started making his Merz works in 1918 – paper pictures and shallow relief constructions with all kinds of detritus he found on the street. Schwitters’s aim was to create works of art that embraced all different branches of art. It is John Heartfield who claimed to have invented photomontage, saying that he was already cutting and pasting photos in the trenches in 1915. He called himself “Der Monteurdada.” Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann named their process “photomontage” because they refused to play the part of the artist. They regarded themselves as engineers and their work as constructions which they assembled. Hannah Höch’s klebebilder are some of the most iconic works of the collage style from that period. As a child, Höch was already making paper collages. It could be said, then, that she rediscovered the method in 1918 when she discovered montaged oleographs on a trip in the Baltics with Hausmann. After this, she started creating her photomontages, using the child-like technique of replacement – the wrong head on the wrong body, reshuffling images, etc. With her works, she explored gender roles and politics, calling into question the very way society viewed itself.

Surrealism

For the Cubist artists, papier collé had opened onto construction and design. The Dadaists and their techniques of relief assemblage, overpainting and photo-collage influenced Surrealism. For the Surrealist artists, “collage” no longer had to do exclusively with paper and glue. The Surrealists were enchanted with text. Max Ernst blended the visual and the verbal in his collage novels from the late 1920s. In 1930, Louis Aragon organised an exhibition dedicated solely to collage at the Galerie Goemans. It included works by Arp, Braque, Dali, Duchamp, Ernst, Gris, Magritte, Man Ray, Miró, Picabia, Picasso and Tanguy. Man Ray and Picabia were included in this exhibition, even though they did not actually make collage but did work with the collage principle. Aragon argued that Man Ray’s rayographs should be linked to collage as a philosophical operation. Yves Tanguy, in the mid-20s, was working with a papier decoupée technique – cutting out shapes and figures –, while Max Ernst observed about Magritte that his paintings were “collages painted by hand.” And then, there was Joan Miró. Miró had always been reluctant to describe his works as “paintings.” Already in paintings like Un oiseau pursuit une abeille et la baisse (1927), the viewer is caught between reading and looking. It is the collage-type effect which produces the gap between these two. Soon after, in 1928, he started a series called Spanish Dancer, three works in which he suddenly abandoned literal painting and instead stuck all kinds of objects to a non-canvas surface. It was as though Miró’s paintings had been anticipating collage, and collage was helping him find his freedom from the rigid understanding of what art was and could be.

Matisse Cutouts

In the late 1940s, in the last decade of his life, Henri Matisse made a significant shift in his artistic methodology and turned to cut paper as his primary medium, using scissors as his tool. His new creations were called cut-outs. Using gouache paint, Matisse would colour sheets of paper and cut these sheets into different shapes and sizes. Often, they were inspired by the natural world – flowers and plants – and at other times they were abstract. Then, he arranged those different cut-outs into lively compositions. They started out modest in size, but over time they grew in scale, becoming as large as murals. The cut-out medium allowed Matisse to finally make the kind of monumental works he had wanted to make for a long time, transcending the confines of easel painting and working with a new type of free reign. The paper cut-outs could be pinned into place, easily rearranged, and seamlessly fused colour with his signature arabesque lines. His line drawing, he had once said, most directly translated his emotions. Now, with the cut-outs, his saw himself as drawing with scissors.

“[Ann Ryan's] small, dense abstractions were looking inward at the time of large-scale Abstract Expressionism. Yet she was still creating her own monumental abstractions in her head, she had a monumental vision on a very intimate scale.” - Pavel Zoubok

Collage in Post-War New York

1922, Peggy Guggenheim had married the Surrealist Laurence Vail in Paris, who was also a maker of collage. She became acquainted with many Surrealists and hosted the “Exhibition of Collages, Papiers-collés and Photomontages” at her Guggenheim Jeune gallery in London in 1938, installed by Roland Penrose of the London Gallery. The exhibition included works by Picasso, Arp, Ernst, Schwitters, Taüber-Arp, Vail and others. In 1941, Guggenheim, Ernst, the Bretons, and other Surrealists sailed for New York to flee the war.

By 1942, Guggenheim had already opened her Art of This Century gallery in New York. It became the place where some of the most audacious, avant-garde art of the times was shown. In 1942, Laurence Vail and Joseph Cornell exhibited collage works there and Marcel Duchamp showed his Box-Valise. Joseph Cornell is particularly interesting as a complex, shy figure who lived all his life with his mother and never had a formal art education. Yet, his Surrealist assemblage works housed in shallow wooden boxes were to make him one of the most important artists of the 20th century working in collage and assemblage. Despite his reclusive nature he cultivated many friendships with great artists including Marcel Duchamp, Lee Miller, Susan Sontag and Yayoi Kusama.

If The Art of This Century gallery already provided a space for the European émigré avant-garde artists, it also became the concentrated hub around which cutting-edge New York abstract artists began to gather. In 1945, Guggenheim invited Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock and William Baziotes to submit collage works for an exhibition entitled “Exhibition of Collage.” For Motherwell, collage was a way to evade representation and to incorporate bits of the everyday world into his pictures. He referred to collage as “both placing and ellipsis.” Guggenheim said of Pollock that he didn’t have a particular feel for collage, but that she was surprised at the violence with which he attacked his material. Pollock’s wife Lee Krasner, on the other hand, experienced an entire phase of collage during which she truly came into her own. It was around the time that Pollock was lost in his alcoholism and unable to paint that she retreated to her little studio and found solace in the cutting, tearing, and pasting of her collage work. Remarkably, Krasner often used shreds from her old, discarded paintings, and even Pollock’s ones as well. Of her collage-work, she once said: “My collages have to do with time and change.”

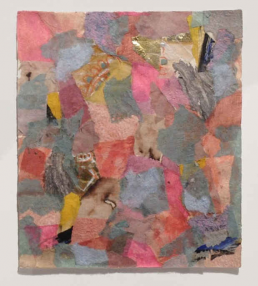

Exhibiting alongside Krasner in 1951 was the collage artist Ann Ryan. Ryan had seen a Kurt Schwitters show in 1948 and became deeply inspired. Collage-specialist Pavel Zoubok of Pavel Zoubok Fine Art describes her as taking on Schwitters’s role in her time. Incredibly, Ryan rarely worked on a larger scale than postcard size. As Zoubok explains: “Her small, dense abstractions were looking inward at the time of large-scale Abstract Expressionism. Yet she was still creating her own monumental abstractions in her head; she had a monumental vision on a very intimate scale.” Other Abstract Expressionists who engaged with collage at the time include Grace Hartigan, Franz Klein and Robert Goodnough.

California Collage

Initially, after the end of the Second World War, artists on the West Coast had little exposure to European modern art and the New York art world. Californian art was therefore, in a sense, free to develop fully of its own accord. Collage and assemblage became important elements of this development. Clay Spohn, for example, who had studied under Fernand Leger in Paris in the 1920s, made mixed media-works and assemblage from all kinds of found objects – scrap metal and other cast-off materials. Los Angeles after 1945 became a melting pot of cultures, and artists like Bertold Brecht and Man Ray even lived there for some time, bringing a touch of Europe and its avant-garde with them. It is around that time in LA that Wallace Berman started making his quasi-religious assemblages revolving around the relationship with his wife.

In San Francisco, Beat culture was making waves with figures like Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. Beat was all about the magic of unnoticed things, it was about “finding” and “experience.” Therefore, it shared many affinities with the collage practice from the visual arts. Most of the Beat collage artists like Wally Hedrick and Jay DeFeo had never even heard of or seen works by Schwitters, Höch, Heartfield or Picasso. Thanks to Man Ray’s presence in LA in the ‘40s, the French Surrealists were more available. Other California artists immersed in the collage medium include Bruce Connor and Ed Kienholz, whose raw, angry and politically charged collage and assemblage work helped pave the way for Pop Art collage.

Collage in Pop Art

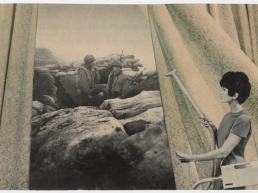

Pop Art emerged in the UK with the 1950s Independent Group. Eduardo Paolozzi and Richard Hamilton, both members of the group, made ample use of the collage method. Paolozzi created collage-type scrapbooks while Hamilton juxtaposed all sorts of materials. His collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? from 1956, often referred to as the first work of Pop Art, presents an interior scene with all kinds of different objects, made up from various materials. My Marilyn from 1965 is made from oil paints and photographic sheets on panel. In the States, at the peak of the Vietnam war, Martha Rosler started creating photomontages reminiscent of John Heartfield, critiquing the military conflict and the complacency of the American consumer. Meanwhile, Rosalyn Drexler collaged pictures from B-movies and tabloids directly onto her canvases, and then painted over them in a very neat, flat style. Collage fit perfectly with Pop Art’s quick, sharp, often witty mirroring of the times.

The Continuation of Collage

This detailed and eclectic timeline of collage offers a deep insight into the important periods and artists in the history of collage art. Unfortunately, it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss all the contributors to this artistic method. Yet it has become clear that collage has been telling the story of each different artistic generation and the world they experienced in fascinating ways. In the words of Pavel Zoubok: “Collage is the most representative of where we’ve been for the last 100 years.”

Today, many young artists continue to work with collage. It is a language of its own, a specific way of thinking, seeing, working and being. Zoubok explains: “When culture becomes increasingly hands-off, we as human beings go back to hand-crafted work because humans have a visceral, primal need for tactility and connection and feeling rooted in some way, in a culture, a tradition, or a geographical location. Young artists return to this world where they tear, rip, paste, work with their hands.”

Zoubok continues to note that collage can be understood as the foundation of the digital experience – its layering and interpolation are rooted in collage culture. He explains: “Hybrid art making and thinking are the foundation of how contemporary aesthetics and contemporary life works.”

Read our next chapter on collage to discover five extraordinary contemporary collage artists around the world working with the medium in innovative ways.

Special thanks to Pavel Zoubok for the invaluable insight and information he provided during the research stages of this article.

Relevant sources to learn more:

- Brandon Taylor: Collage – The Making of Modern Art

- http://pavelzoubok.com