Articles & Features

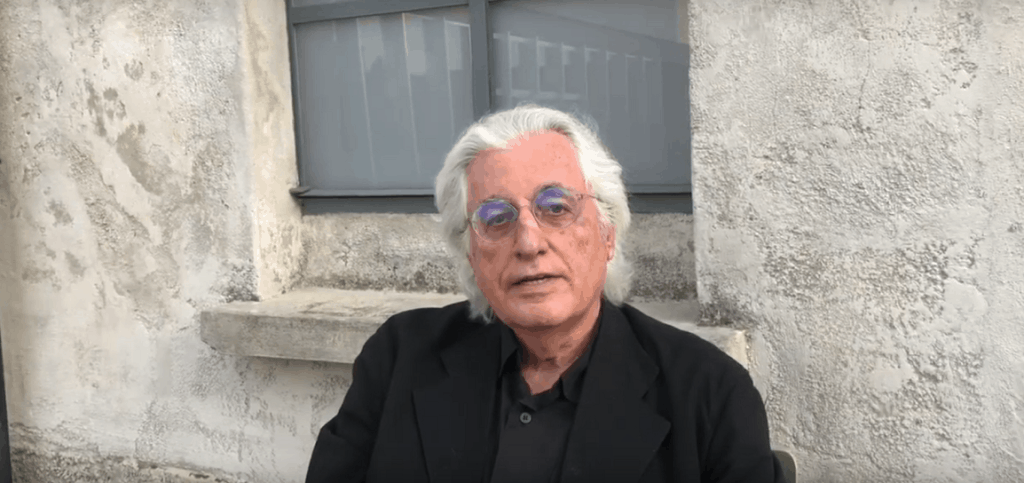

Germano Celant: Critic, Curator, Mythmaker

“What is happening? Banality is entering the arena of art. The insignificant is coming into being or, rather, it is beginning to imposing itself. Physical presence and behaviour have themselves became art. (…) We are living in a period of deculturation. Iconographic conventions are collapsing, symbolic and conventional languages crumbling.”

Germano Celant

Germano Celant and the Arte Povera Movement

It’s 1967, amid revolutionary movements, turmoil, and student protests, and the pages of Flash Art reveal to the world a radical manifesto, “Notes for a Guerrilla War”. “A new attitude for taking repossession of a ‘real’ dominion over our existence leads the artist towards continual forays outside of the places assigned to him, eradicating the cliché that society has stamped on his wrist. No longer among the ranks of the exploited, the artist becomes a guerrilla fighter, capable of choosing his places of battle and with the advantages conferred by mobility, surprising and striking, rather than the other way around”.

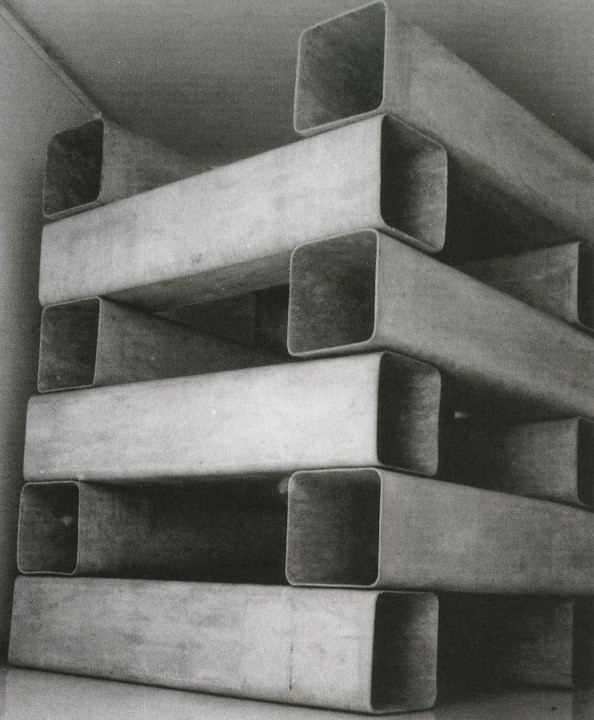

The essay presents for the first time a new form of art, defined ‘Arte Povera‘, literally “poor” or “impoverished art”, pursued by a heterogeneous group of artists united in their common tendency to use every-day, “worthless” materials, to attack the established social and cultural values, and which also refuse to engage with traditional artistic media and languages. It states: “there’s an abolition of all positions couched in terms of categories (either “pop” or “op” or “primary structures”) in favour of a focus on gestures that add nothing to our refinements of perception, that do not counterpose themselves as art to life, that do not lead to the fracture and creation of two different planes of the ego and the world, and that live instead as self-sufficient social gestures, or as formative, compositive, and anti-systematic liberations, intent upon the identification of the world and the human individual”.

The author of the powerful essay was 27-year old Germano Celant and around him this group of artists gathered, finding in his pivotal figure an identity to relate to as well as a consistency of position. Celant, who had taken his first steps in the art world as an editor for the culture magazine Marcatrè, had already made his name in his home-town city of Genoa in northern Italy with the organisation of the watershed collective exhibition Arte Povera – Im Spazio at Galleria La Bertesca, two months before. That was the very first use of the term ‘Arte Povera‘, applying this attitude-label to a wide array of works focused on the exploration of space through the physical qualities of humble materials, and featuring artists like Alighiero Boetti, Luciano Fabro, Jannis Kounellis, Pino Pascali, and Giulio Paolini among others, and also representing the beginning of Italian artists’ unrefined and reactionary response to the polished aesthetics and smooth surfaces of American Pop and Minimalism, both of which had assumed dominance as polar codes in international artistic production.

Despite Arte Povera officially ending as an organized movement in the 1970s, its impact and influence can still be perceived today and the majority of the group is still active in the art world. As Celant told the Italian newspaper La Repubblica a few years ago: “I didn’t invent anything. Arte Povera is an expression so broad that it means nothing. It doesn’t specify a pictorial language, but an attitude”.

Celant’s career began with a clever combination of curatorship and writing, and this parallel activity never stopped during the entirety of his prolific career.

At times one only needs a single potent intuition to ignite a spark and catalyse immense change. For Germano Celant, the identification of Arte Povera was that intuition: the manifesto did not go unnoticed and Celant immediately received international attention.

Last week, at the age of 79, Germano Celant died in Milan, his remarkable career tragically cut short by COVID-19-related complications.

International Career

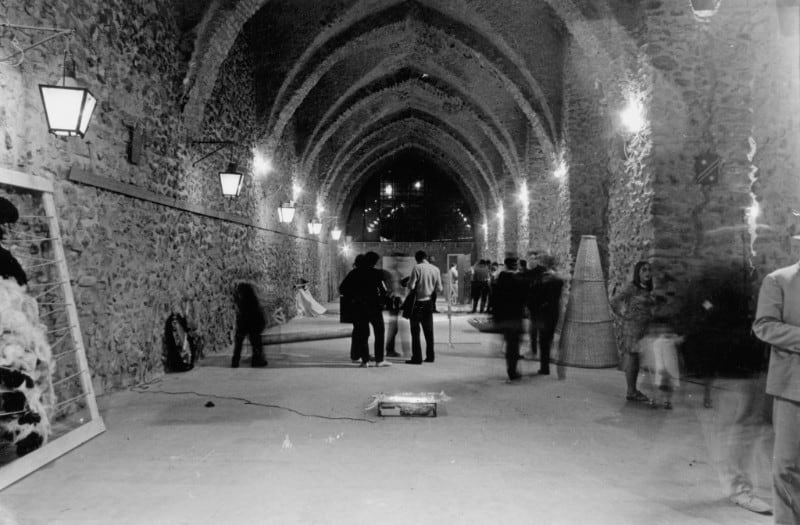

After the publication of the Arte Povera manifesto, a remarkable string of memorable exhibitions placed Celant in the international spotlight; first of all the seminal Arte Povera+Azioni Povere in Amalfi, in 1968, a three-day performance event including interventions by Michelangelo Pistoletto, Mario and Marisa Merz, a reflection on the performative and ephemeral aspect of contemporary art within the unexplored context of public space. Celant’s tendency to push the boundaries and his undeniable ability to predict where art was headed revealed itself clearly. Always a visionary, it was Celant who recognised the emergent trend of what today we would call “environmental art”, including aspects of this burgeoning trend within his Ambiente/Arte staged as part of the 1976 Venice Biennale.

Arte Povera+Azioni Povere also anticipated Harold Szeemann’s celebrated landmark exhibition When Attitudes Become Form (1969), which included a number of artists promoted by Celant among a group of sixty-nine internationally acclaimed artists, definitively establishing the connection between Arte Povera and Conceptualism. The show caused a sensation, and it is no wonder that Celant decided to restage it at Fondazione Prada in 2013 as an “exploration of the fluid exchange between material and temporal space”.

His remake was contentious, especially regarding his decision to outline in white on the floor the silhouettes of artworks from the original show that, for whatever reason, could not be displayed.

In 1988, Celant was appointed as senior curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, a prestigious role he held until 2008 and which allowed him to stage remarkable exhibitions of international contemporary artists, while continuing to champion the Italian avant-garde. Particularly memorable was The Italian Metamorphosis, 1943–1968 an exhibition from 1994: an immense and interdisciplinary survey of Italian art from the immediate postwar to the swinging years of la Dolce Vita. On that occasion, for the first time, he presented fashion as a form of cultural expression – a theme that was to become further developed in the following years and another aspect of museological evolution that he participated in ushering into contemporary institutional practice. In 1996 he curated the first Fashion Biennial in Florence combining contemporary artists with fashion designers, and three years later controversially awarded Giorgio Armani a full retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum. Celant, immediately recognisable for his minimalist monochromatic clothing palette, was a pioneer in discerning the potential of the art-fashion combination and, while the relationship between the two is now universally accepted, it was highly unusual inter-disciplinary merging when presented at the time.

In the nineties, a series of successes followed: in 1995, he accepted the role of Artistic Director of Fondazione Prada and, two years later, he was entrusted with the curatorship of the Venice Biennale.

Not only did he curate an endless number of exhibitions but also was the author of dozens of books and catalogs raisonnés. He oversaw the work of Piero Manzoni, Mimmo Rotella, Dan Flavin, Walter de Maria, and Anish Kapoor among many others, until his last, admired retrospective of Jannis Kounellis in 2019.

Nonetheless, his career has not been without controversy and criticism. He was often accused of cultural bias. “I have often been accused in Europe of being pro-American and in the United States of being pro-European”, he told the New York Times.

But as the decades went by, he was also accused of selling out to the omnipresence of commercialism, considering art as any other product to be consumed. When, in 1997, he served as artistic director of the Venice Biennale, Roberta Smith from The New York Times wrote that the exhibition was “weighed down by big-name, over-the-hill talents, including many artists with whom Mr. Celant has worked in previous exhibitions. Walking through it, one can almost hear the sound of chips being cashed in”.

He also caused an outrage by curating the exhibition Art & Foods for the Expo in Milan, in return for an exorbitant €750,000 contract.

Germano Celant’s legacy

Despite his critics and the rifts with younger curators, it is undeniable that Germano Celant transformed the curatorial game, making his authorship of overview into one of the principal protagonists of the exhibition circuit, and making the curator as celebrated and as much of a draw as the artists themselves.

If, on the one hand, his name will be forever bound to the Arte Povera movement and acclaimed for bringing postwar Italian art to international prominence, on the other his resolute curatorial vision ensured his position as a watershed figure and radically changed not only the way art is looked at, but also the methodology by which it is produced, displayed and theorized.

Relevant sources to learn more

Guggenheim Museum and Foundation

Review of “The Italian Metamorphosis 1943-1968”

Fondazione Prada

Virtual Tour of Arte Povera at Magazzino Italian Art Foundation, NY