Articles & Features

The Harmony of Form and Function:

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Organic Architecture

“The mission of an architect is to help people understand how to make life more beautiful, the world a better one for living in, and to give reason, rhyme, and meaning to life”.

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1957

In our daily life, we seem to encounter the term ‘organic’ all around, from supermarkets’ food shelves to clothes and cosmetics. Despite its massive usage, the term is overloaded with vagueness and mixed-up meanings; what does it really mean? Scientifically speaking, it refers to the compounds of carbon, therefore indicating materials derived from living organisms, animals as well as plants. When it comes to the market, things get trickier as the label indicates certified products complying with certain production standards that, however wholesome the label implies, vary widely worldwide.

Nevertheless, in the early decades of the twentieth century – long before the word ‘organic’ had entered the lexicon of grocery shops and the world of products – the term gained entry into the architecture field resulting in the conception of one of the most groundbreaking and impactful design philosophies in modern times, Organic Architecture.

But what is meant by this term, Organic Architecture? Let us discover, along with the life and work of the man behind it: legendary American architect Frank Lloyd Wright

“There is no architecture without a philosophy. There is no art of any kind without its own philosophy”.

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1959

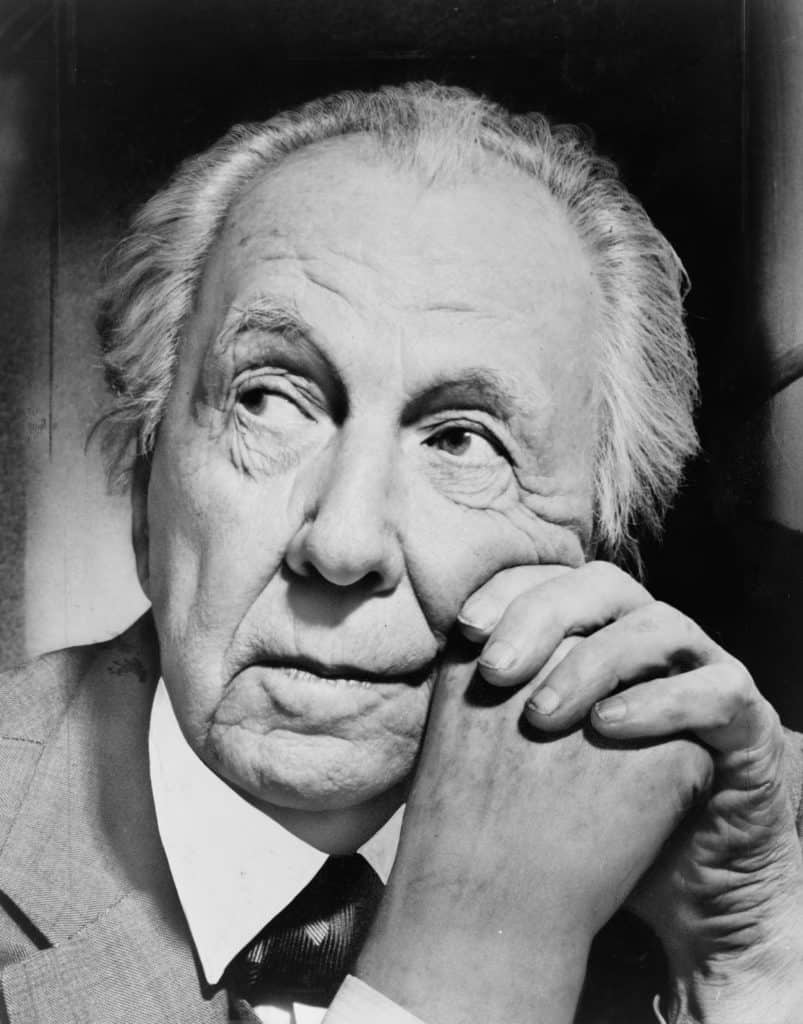

Frank Lloyd Wright, American architect

Frank Lloyd Wright’s prolific career – he designed 1,114 buildings of all types, 532 of which were realized – began in 1887 when, in search of employment, he moved to Chicago from Madison, Wisconsin.

There, he worked for two different architectural firms until he was hired by the prestigious Adler and Sullivan studio, finding in the latter, the “father of skyscrapers”, a mentor and a source of inspiration. Probably conditioned by his mother, who had prophetically hung engravings of the English cathedrals by Timothy Cole in his childhood nursery as an encouragement, Wright had always wanted to become an architect. However, he belongs to the surprisingly long string of exceptional architects without an architecture degree – the list includes, among others, Louis Sullivan himself, Le Corbusier, and Mies van der Rohe.

Wright was admitted to the University of Wisconsin but left the school before receiving the degree; actually, there is no evidence of his high school graduation either. Anyway, once in Chicago, along with an exclusive five-year contract, Wright received from Sullivan a loan to buy a lot in the suburb of Oak Park and build a house for himself and his wife, Catherine Lee Tobin, as well as their growing number of children.

Driven by the escalating expenses, due both to the growing family and his penchant for splurging on lavish cars, apparel, and home furnishings, the architect began to accept independent commissions for residential buildings, designing at least nine in spite of the exclusivity clause with Adler and Sullivan.

These “bootleg” projects – as he called them himself – brought the architect to experiment with geometric shapes and volumes, and features that would become his signature, such as the bands of horizontal windows, appeared for the first time in these early works. In 1893, Sullivan found out about Wright’s extra activity: one of his “bootleg” buildings was just a few blocks away from Sullivan’s townhouse in Chicago and he immediately recognized Wright’s already unmistakable style, ultimately charging him with breach of contract and putting a bitter end to their both professional and private relationship.

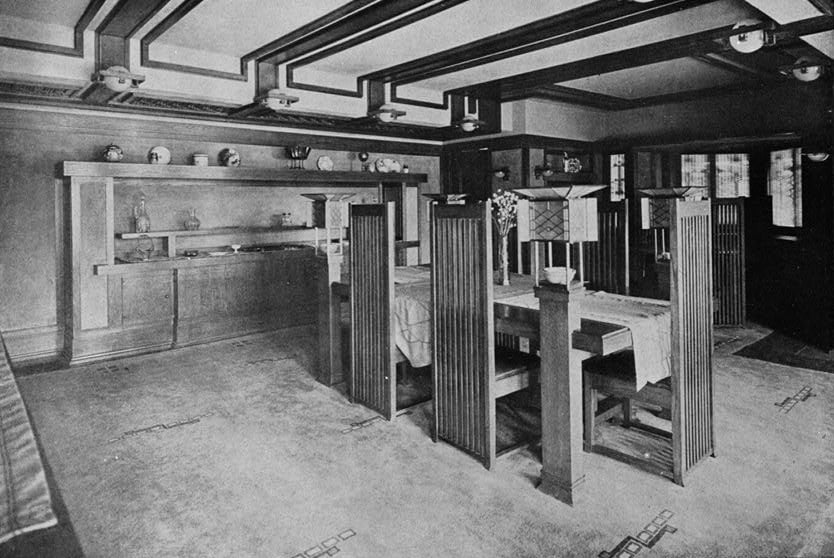

This divergence turned, in fact, into an opportunity for Wright: he began working on his own, determined to design the first genuinely American architecture at a time when the country was struggling to define its identity, in most cases mimicking Classical European architectural styles. In his quest, the architect totally reinvented the planning of houses, developing what has come to be known as the Prairie Style: single-story residential houses featuring a marked horizontal theme to complement the flat landscape of the prairie around Chicago; low-pitched roofs and long rows of casement windows realized with the employment of natural and locally available materials: stone and unpainted wood.

Recognizing the power of space and structure to elicit conviviality and social values, Wright used to design free and open environments arranged in open floor plans with an emphasis on elements such as the dining table, the central chimney, and the terrace. Among the most magnificent examples of this style, remain the Robie House in Chicago and Coonley House in Riverside, Illinois.

Wright’s ideas were reflected also in non-residential, monumental projects such as the Unity Temple in Oak Park, Illinois, and the Larkin Administration Building in Buffalo, New York (demolished in 1950) where he adopted innovations like hanging bathroom fixtures, glass doors, and air-conditioning. In 1909, Wright left his family and set sail to Europe with Mamah Borthwick, one of his clients’ wife. During the European stay, the architect worked on two publications that received international critical acclaim raising his status to one among the top living architects.

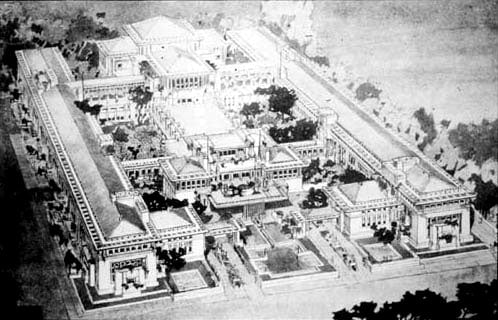

His worldwide recognition was such that in 1915 the Japanese Emperor commissioned him with the design of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo: seven years later a splendid, groundbreaking building was terminated. Only one year after its completion, the Great Kanto Earthquake devastated the city leaving Wright’s Imperial Hotel as the only large structure intact.

Back in the States, Wright designed a new home in Spring Green, Wisconsin, the land of his maternal ancestors, and named it Taliesin after a character of Welsh mythology. After multiple reconstructions due to two major fires – one caused the tragic death of Mamah Borthwick and her two children – he would eventually transform it into an architectural apprenticeship school, the “Taliesin Fellowship”, still active today.

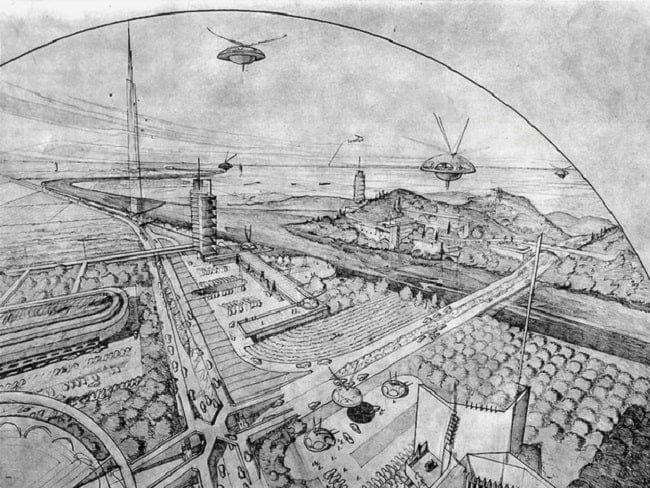

Wright also dedicated himself to lecturing and writing. In 1932, issued two major publications: An Autobiography that had a great influence on younger generations of architects and, secondly, The Disappearing City where he presented Broadacre City, his utopian vision for harmonious and affordable living as a response to the financial crisis of 1929.

During his seventy-year career, newspapers often put Wright in the public eye not only by reason of his artistic and technical talent but also for his private catastrophes and dramas – his three wives, eight children, and extra-marital relationships caused a certain scandal – as well as his rather narcissistic personality. In fact, to disdain other architects, he fiercely refused to join the American Institute of Architects, even after the organization awarded him its gold medal in 1949.

In the mid-thirties, Wright was considered one of the most influential American architects, yet his time seemed to be coming to an end. Far from it, in his sixties, he returned to the architectural scene with renewed creative energy and designed two of the most potent examples of 20th-century architecture: Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, and The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum on Fifth Avenue in New York City. The latter, conceived to house Guggenheim’s private collection of non-objective art and initiated in 1943, consumed the last 16 years of Wright’s life, and neither Guggenheim nor the architect himself, saw it completed.

In 2019, eight projects by Frank Lloyd Wright were declared Unesco World Heritage sites representing the only US modern architecture on the prestigious list.

“No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together, each the happier for the other”.

Frank Lloyd Wright, 1932

Organic Architecture

In the torrent of creation and production that was Frank Lloyd Wright’s life, he designed private houses, hotels, schools, offices, skyscrapers, museums, and churches, tailoring each of them according to the clients’ needs and providing them with specific features that made them functional and unique at the same time, as well as unmistakably by his hand. However, a common thread characterises his life’s work, the architect himself called this leitmotif that runs the gamut of his entire production ‘Organic Architecture’. In this case, some misconceptions see the term ‘organic’ as a synonym of ‘natural’ identifying Organic Architecture in the use of curved and free forms, emulating natural shapes, or in the use of environmentally sustainable materials. This is to misinterpret the term. Whilst natural materials are commonly utilised in Organic Architecture to reinforce the connection between the interior and the external environment, this is rather a consequence than a principle. In fact, Organic Architecture is not a stylistic or aesthetic movement, but instead a particular approach or, better yet, a philosophy.

The theory is concerned with the idea that all elements belong together: from floor and doors to furniture and natural surroundings, all components relate to one another creating a ‘unified organism’, hence the name. To say it in Wright’s own words: “Organic Architecture is an architecture from within outward, in which entity is an ideal. (…). Organic means, in the philosophic sense, entity. Where the whole is [to] the part as the part is to the whole and where the nature of the materials, the nature of the purpose, the nature of the entire performance becomes a necessity”.

While his mentor Louis Sullivan professed that “Form follows function”, to Wright “Form and function are one” in an all-embracing sense of unity achieved by adopting empathetic and site-specific design strategies.

As cornerstones of the philosophy, Wright established simplicity, humanity, integrity, and connection; these principles altogether would nourish the lives of a house’s inhabitants and consequently strengthen the whole society’s well-being.

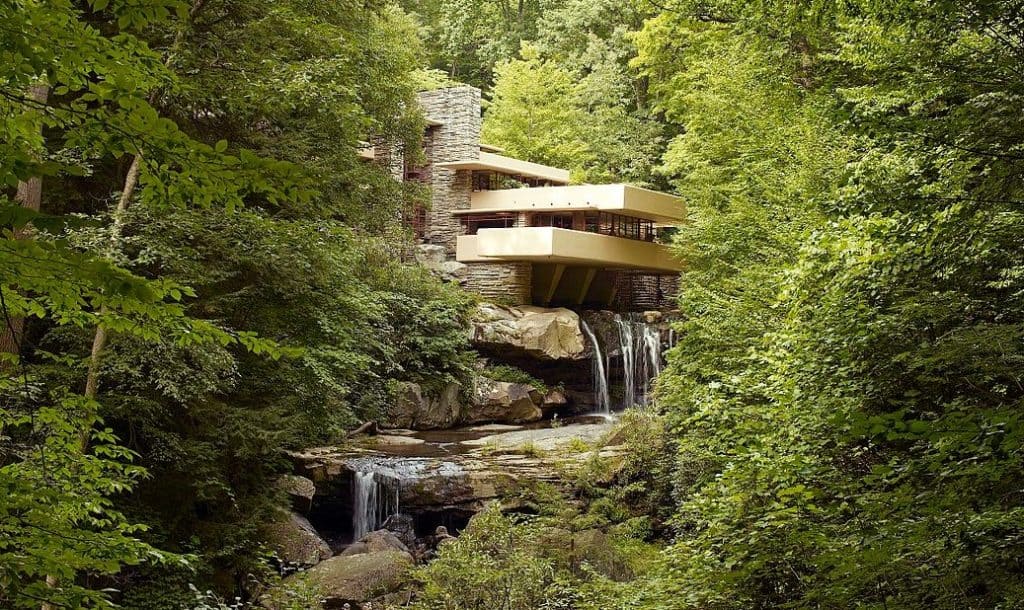

The absolute masterpiece of Organic Architecture is Fallingwater, Wright’s project for Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann’s summer house in Bear Run, Pennsylvania – also considered the “best all-time work of American architecture” by the American Institute of Architects.

The Kaufmann, a prominent family from Pittsburgh, first met Wright in 1934 while visiting their son who had begun an apprenticeship at the Taliesin Fellowship. Already familiar with the architect’s ideas, the couple asked Wright to design a weekend residence on their property in rural Pennsylvania. Sharing with the family a mutual aesthetic sensibility and a passion for nature and new ideas, Wright seized upon the occasion and created the most thorough celebration of the couple’s favorite landscape, the waterfall on Bear Run. Instead of a building overlooking the waterfall, he designed a house sitting on top of it, as an integral part of the natural surroundings.

Reminiscent of Japanese traditional architecture, Fallingwater’s exterior and interior spaces merge seamlessly, and different rooms create a single continuous space; suspended above the stream, cantilevered terraces of local sandstone blend with the rock formations, an unprecedented example of architectural geology. About Fallingwater, Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic Paul Goldberger stated: “Great architecture, like any great art, ultimately takes you somewhere that words cannot take you at all. Fallingwater does that the way Chartres Cathedral does that. There’s some experience that gets you in your gut and you just feel it, and you can’t quite even say it. My whole life is dealing with architecture and words, and at the end of the day, there is something that I can’t entirely say when it comes to what Fallingwater feels like”.

A century after their conception, Organic Architecture’s principles still prove their importance. Even if broadening and slightly shifting in meaning to embrace environmental sustainability, it appears that Wright’s ideas still have a role to play in the development of contemporary architecture. After all, it was Wright himself who prophesied: “As for the future the work shall grow more truly simple; more expressive with fewer lines, fewer forms; more articulate with less labor; more plastic; more fluent, although more coherent; more organic”.

Relevant sources to learn more

Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Fallingwater

Gesamtkunstwerk. The Total Work Of Art Through The Ages.