“In the year 1913, trying desperately to free art from the dead weight of the real world, I took refuge in the form of the square.” – Kazimir Malevich

Suprematism definition: what is Suprematism?

Suprematism was an abstract art movement founded in Russia during the First World War. Interested in pure abstraction, the Suprematists searched for the ‘zero degree’ of painting, the point beyond which the medium could not go without ceasing to be art. In order to achieve this point, simple motifs were used which best articulated the shape and the flat surface of the canvas. The square, circle, and cross became the group’s favourite motifs. For Suprematist artists, the visual phenomena of the objective world were in themselves meaningless; what was instead significant was feeling. The word “Suprematism” was coined to describe the movement, as one that would lead to the supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.

Key period: 1913-1920s

Key regions: Soviet Union

Key words: pure abstraction, geometric shapes, pure feeling and perception, mysticism

Key artists: Kazimir Malevich, Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Ivan Klyun, Mikhail Menkov, Ivan Puni, Olga Rozanova, El Lissitzky

Origins of Suprematism

During the period of the First World War, Russia was a hub for cutting-edge avant-garde art. Constructivism was established as an influential avant-garde art movement, while Natalia Goncharova and her partner Mikhail Larionov were embarking on their own experiments in art under the term “Everythingism.” At the same time, Kazimir Malevich was working on some of the most radical developments in abstract art of his time, and developing Suprematism.

He created the first works related to Suprematism in 1913 while working on the background and costume sketches for the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun. At the time, Malevich was still heavily influenced by Cubo-Futurism, and Suprematism is in a way like a logical extension of Futurism’s preoccupation with movement and Cubism’s reduced forms and multiple perspectives.

Searching for the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts,” Malevich was deeply influenced by avant-garde poets and was interested in going against the rules of language and reason. He believed there were only delicate links between words, signs, and the objects they denote. This inspired him to see the possibilities of a totally abstract art and incited him to search for the barest essentials of art.

In 1915, Malevich was joined by Russian artists Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Ivan Klyun, Mikhail Menkov, Ivan Puni and Olga Rozanova. Together, they formed the Suprematist group. They unveiled their new works at The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10 (1915-16), in which they showed pieces featuring an array of geometric shapes suspended above a background that was either white or light-coloured. These compositions held a specific sense of depth through the variety of shapes, sizes and angles depicted. The squares, circles and rectangles thus appeared to be moving in space. Alongside the exhibition, Malevich published a manifesto called From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism in Art. In it, he claimed to have transcended the boundaries of reality and to have crossed over into new awareness.

“Under Suprematism I understand the primacy of pure feeling in creative art. To the Suprematist, the visual phenomena of the objective world are, in themselves, meaningless; the significant thing is feeling, as such, quite apart from the environment in which it is called forth.” – Kazimir Malevich

Key ideas behind Suprematism

One of the foremost inspirations for Malevich in his move towards Suprematism was avant-garde poetry and literary criticism. The Russian Formalists were an influential group of literary critics who opposed the idea that language is a simple and transparent means towards communication. For them, words were not necessarily easily linked to the objects they denoted. Words and art, then, could create a new, strange, and fresh perspective of the world. Suprematist artists aimed for the same thing – they wanted to remove the real world completely in order to get the viewer to contemplate the world instead through the transcendental experience evoked by a totally stripped-down, abstracted art. Furthermore, Malevich took inspiration from Russian folk art and the traditions of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Famous Suprematist artists and artworks

Kazimir Malevich (1879 – 1935)

Founder and central figure of Suprematism, Malevich had quickly assimilated the movements of Impressionism, Symbolism and Fauvism, and after visiting Paris in 1912, Cubism, to ultimately develop a gradually simplified style consisting of pure geometric forms and their relationships to one another. This radical experiment came close to a type of mysticism, evident in his works like Black Square (1915), a black square on white, which became the centrepiece of Suprematist art as well as the most radically abstract painting known to have been created so far.

The artist painted a second Black Square around 1923 and some believe that the third Black Square was painted in 1929 for Malevich’s solo exhibition, because of the poor condition of the 1915 version. One more Black Square, the smallest and probably the last, may have been intended as a diptych together with the small Red Square realized for the exhibition Artists of the RSFSR: 15 Years, held in Leningrad (1932).

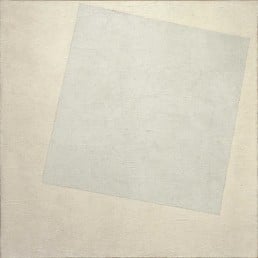

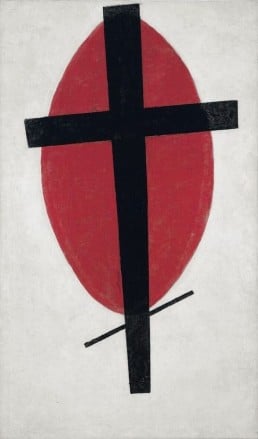

Malevich divided Suprematism into three stages: “black,” “coloured,” and “white.” The movement started with the black stage and the ‘zero degree’ of painting, as exemplified by his Black Square (1915). The coloured stage, also referred to as Dynamic Suprematism, was particularly exlored by artists such as Ilya Chasnik, El Lissitzky and Alexander Rodchenko and focused on the use of colour and shape in order to create the sensation of movement in space. Finally, there is the white stage, which could be seen as the culmination of Suprematism. During the Tenth State Exhibition: Non-objective Creation and Suprematism in 1919, Malevich exhibited pieces from his white stage. His masterpiece was White on White (1918), with which he dispensed with form entirely and only represented the idea.

El Lissitzky (1890 – 1941)

Though he also worked in the Constructivist style, El Lissitzky worked intensively with Suprematism in the years 1919 to 1923, ultimately developing his own style of Suprematism called “Proun”. Among the most important artists influenced by Malevich, it was El Lissitzky who popularized the Suprematist ideas abroad. During a 1923 trip to Berlin, where he exhibited at the Hanover and Dresden showrooms of Non-Objective Art, El Lissitzky was in fact in close contact with Theo van Doesburg, forming a bridge between Suprematism and De Stijl and the Bauhaus.

The decline and legacy of Suprematism

Following the Russian Revolution in 1917, attitudes towards art started changing. By the late 1920s, Social Realism had become the only accepted style and all avant-garde art was condemned by the Stalinists. Malevich himself stopped painting altogether between 1919 and 1927 in order to focus on his theoretical writings. He eventually returned to painting and even painted in the style of Social Realism, while always finding a way to add the signature mark of his own style and ideas. In his Self-Portrait (…), for example, he signed the canvas in the bottom-right corner with a little black square. Nonetheless, the movement’s heyday had come to an end.

In the realm of abstract art, however, the influence of Suprematism was far-reaching. El Lissitzky used Suprematist concepts and forms, which played a role in developing the Constructivist movement. He was also instrumental in promoting Suprematism outside Russia, inspiring artists like Laszlo Moholy-Nagy. Malevich’s notion of transcendence in art can be seen in the Theosophy-inspired geometric abstraction of Piet Mondrian. In 1936, the groundbreaking exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art at the MoMA included several of Malevich’s Suprematist works, which greatly impacted American modernism. Today, echoes of Suprematism can still be detected in contemporary architecture, for example in the recent “Suprematist” work of Zaha Hadid.