Articles and Features

Agents of Change: How Contrapposto Added Dynamism and Emotion to Art

By Shira Wolfe

In our article series, Agents of Change, we explore developments and innovations, both technical and technological, that had a seismic impact on artistic production and consequently changed it in key ways, forever. We learn how artists and the tools at their disposal evolved over the years and gave rise to new forms of art and ways of making them. Last edition covered the evolution of printmaking in art. This week, we investigate the development of Contrapposto and its impact on art. Contrapposto, Italian for Counterpose, is a sculptural scheme developed by the Ancient Greeks, in which the standing human figure rests his weight on one leg, thereby freeing the other leg, which is bent at the knee. It allowed artists, for the first time in history, to realistically portray the actual shape of human anatomy, and the accompanying subtleties of poise, movement and dynamism in their depiction of the figure.

The Origins of Contrapposto

The Ancient Greeks first developed Contrapposto, in the 5th century BC. Previously, the Greeks were making Kouros sculptures which portrayed figures with their weight evenly divided on both legs, one foot slightly in front of the other, exuding a stiffness and rigidity. Contrapposto arose as an alternative to this. One of the earliest examples of Contrapposto can be found in the Ancient Greek sculpture Dosyphoros (Spear Bearer), which was made in ca. 450-440 BC. Here we see that the curved position of the sculpture creates a much more lifelike quality. The sculpture became an icon of the ideal classical figure for Renaissance artists, who continued to work with and emulate the stance.

Another important example of Hellenistic Contrapposto is the Winged Victory of Samothrace (ca. 200-190 BC), also called Nike of Samothrace. In order to suggest a body in motion, the sculptor positioned Nike in an asymmetrical stance. Her body is sculpted in an S-form. The weight placed on one leg stepping forward and the billowing fabric draped around her body both imply dramatic movement. Initially, Contrapposto presented issues of balance, which artists dealt with by adding props for their figures to lean on.

The Italian Renaissance

Contrapposto was lost during the Middle Ages (also known as the Dark Ages due to the lapses in both Christianity and an elevated cultural aesthetic), and revived again during the Italian Renaissance and Mannerist period, when artists revived this Ancient Greek pose and named it Contrapposto. With their greater knowledge of human anatomy, artists began to emulate the pose, using it not only in sculpture but also in painting.

A famous example of Italian Renaissance Contrapposto is Michelangelo’s David. The evolution of Contrapposto can be seen here in the sense that David’s body is much more anatomically accurate, the weight on his one leg forcing his hips, spine and shoulders to tilt, creating an S-shaped body and communicating an air not only of strength but also idealised natural posture.

The twisted pose of Contrapposto also helped to suggest movement, a clear example of which can be seen in Titian’s Venus Rising from the Sea (1520). Here, the Contrapposto stance helps to create the illusion that Venus is really in motion, just emerging from the sea.

Contrapposto in Art Today

Contrapposto allowed artists to show their skill in ways they were previously unable to do, portraying more movement, reaction and emotion in their subjects. Contemporary artists still make use of the pose, often as a reference to the ancient tradition, but also as a means to create dynamism in their artworks. Take, for example, Bruce Nauman’s video Walk with Contrapposto (1968). Here, Nauman makes his way laboriously through a narrow passageway, while always attempting to maintain the Contrapposto stance. The pose, which was developed in order to make subjects seem more natural and relaxed, instead becomes a great physical constraint. In his 2016 Contrapposto Studies, he continues his research of the pose.

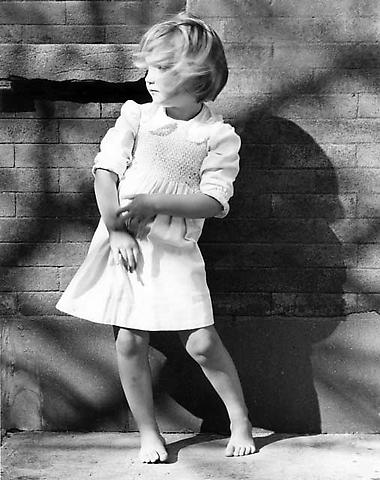

Modern and contemporary photographers, including August Sander and Robert Mapplethorpe, also chose to pose figures in Contrapposto, as a playful nod to former Ancient Greek, Italian Renaissance and Mannerist representations of the body. An example is Mapplethorpe’s portrait of Lindsey Kay (1985), in which the little girl is placed in Contrapposto pose before a brick wall.

Relevant sources to learn more

For more information about the history, development and influence of Contrapposto