Articles and Features

5 Artists Whose Diaries are as Inspiring as their Art

By Shira Wolfe

In the measure that her hope was her art and her art was her heaven, the Diary is Kahlo’s greatest attempt to bridge the pain of her body with the glory, humor, fertility, and outwardness of the world. She painted her interior being, her solitude, as few artists have done.” – Carlos Fuentes in the Introduction to Frida Kahlo’s Diary

Diaries are the most intimate objects people possess. They contain all the elements that make up the human experience, without holding back in any way since they are meant only for the eyes of the author. Each person has their own unique approach to keeping a diary and tracking the experiences of their daily lives and the development of their personal processes. And when artists write diaries, they tend to be filled not only with intimate personal thoughts and fascinating details of their artistic progress, but also with stunning little examples of their art in the form of sketches and studies. In some cases, the diary is really an artwork in and of itself. Take a look at five artist diaries that are truly unique testaments to their authors’ artistic vision.

1. Leonardo da Vinci’s Sketchbooks

Leonardo da Vinci’s sketchbooks are arguably among the most well known in the artist diary genre. They contain extensive drawings, diagrams and notes as studies for his larger works and for his many of his inventions. The legacy of the great Renaissance artist has been preserved in over 7000 pages of personal notes and illustrations. The beauty of these notebooks is that they combine detailed notes and sketches on topics ranging from optics, astronomy and architecture to personal reminders about everyday tasks and things as mundane as an inventory of his clothes. A digitised version of Da Vinci’s Codex Arundel, written in his characteristic left-hand mirror-writing, was published by the British Library in 2013. Spanning 40 years of Da Vinci’s life, the Codex is one of the most fascinating and important notebooks of the artist’s career and contains many of his most famous creations. Aside from engineering diagrams, anatomy studies and artistic sketches, the Codex also contains fables written by Da Vinci, as well as his qualifications for the post of military engineer. The fully digitised Codex Arundel can be accessed here. The Visual Agency has also digitised Da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus, another large collection of his intricately-illustrated notes.

2. Frida Kahlo’s Diaries

No artist diary is as passionate, emotional and vivid as Frida Kahlo’s diary. From 1944-1954, the Mexican artist kept a colourfully illustrated diary overflowing with artworks, sketches, personal musings, dreams, poems and emotional references to her stormy relationship with her husband Diego Rivera. The diary also reveals Kahlo’s courage and suffering in the face of her physical injuries due to an accident which led to over 35 operations in her lifetime. She illustrates her physical disabilities and the constant pain she lives with brilliantly in bold self-portraits throughout the diary, in which she shows her legs as cast in metal, or depicts the supportive corset she had to wear. Carlos Fuentes published a full-colour recreation of Kahlo’s diary in 2005, containing over 70 watercolours that illuminate Kahlo’s deepest inner worlds. Unexpected, completely non-linear, and a colourful ode to a life lived fully in and through art, Frida Kahlo’s diary also offers a kind of solace by showing how even adversity and suffering can be processed through creativity, resulting in radiance and life.

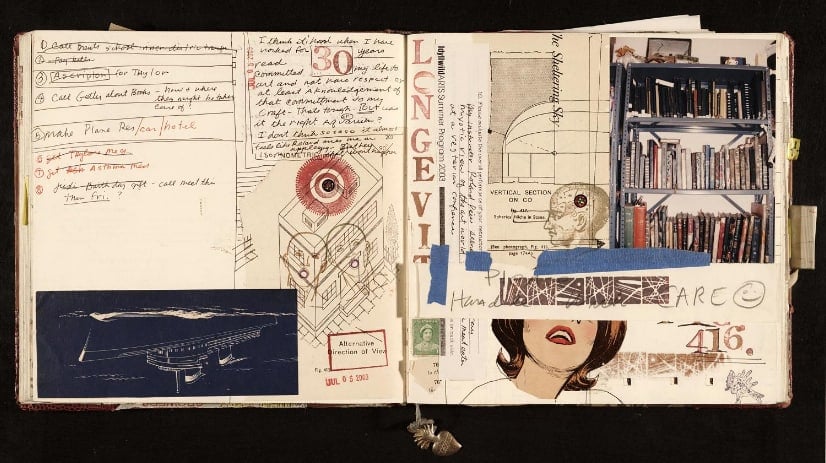

“I call these books ‘reportage.’ There are certain themes that run through the journals consistently—health, motherhood, political things, being an artist, even fashion and television. Originally, I saw them as books for my sons, so they could see my progress through life. Now they’re 126 chapters of a memoir.” – Janice Lowry

3. Janice Lowry’s Diaries

Janice Lowry was an artist known mostly for her intricate collage and assemblage works often created from found, discarded objects. From the age of 11, Lowry kept a diary, using small notebooks to fill with her daily thoughts and with little drawings. She kept this up her whole life, switching to a larger format in the mid-70s. Each of the notebooks spans about four months and records not only to-do lists, personal thoughts and experiences but also impactful world events that happened in her lifetime, such as 9/11. This entry includes her first reactions to the terrorist attacks, such as: “8:45 Eastern time. A second hijacked plane. Oh my God! 50 thousand people work in the trade center.” and “The only solution for me is to do ordinary things.” Alongside her frantic notes are sketches of the planes impacting the World Trade Center, and a collaged dollar bill with one of the teletubbies saying “Uh-oh!” Lowry referred to her notebooks as “reportage.” She originally saw them as books for her sons, so that they could learn about their mother in this way and see her progress through life. They were also a way for her to take her space in the world and show that she existed. The notebooks eventually became some of her most important artworks, which were all acquired by the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art.

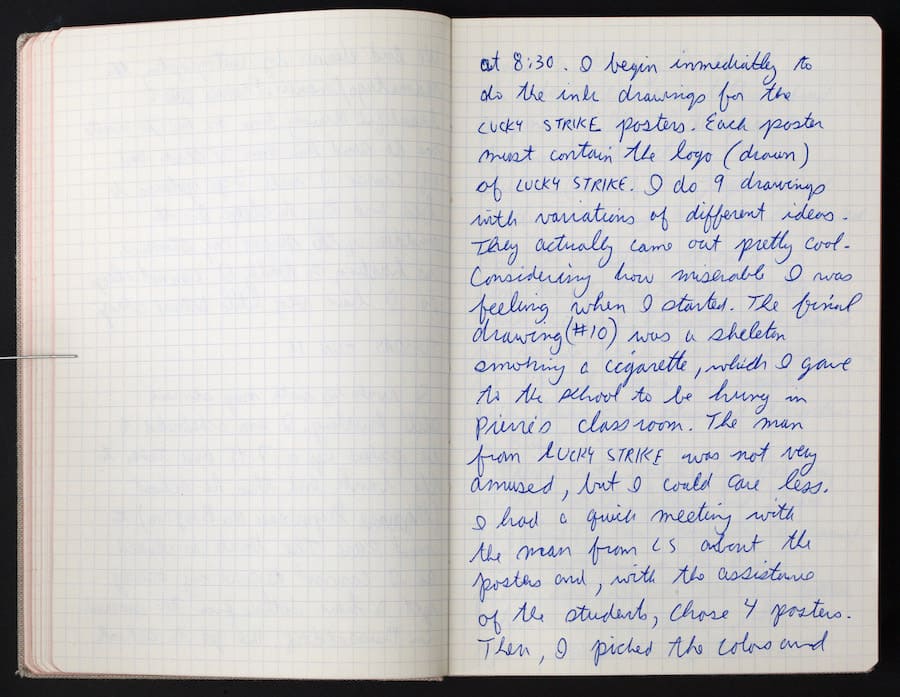

4. Keith Haring’s Journals

Keith Haring was an unmistakable part of the New York art scene of the 1980s, who started out drawing in New York subway stations, inspired by graffiti artists. He wanted to make art accessible to everyone and his colourful motifs such as the radiant baby and the barking dog became icons of the time. But Haring’s creativity wasn’t limited to this large-scale public work. He also kept extensive journals throughout his life, filled with his sharp and witty writing about his work, his relationships and events of his daily life. The journals also contain sketches, quotes and reading lists. It’s a fascinating journey to explore Haring’s journals, as he takes you through disarming moments such as his artistic insecurities early on – moments familiar to many which we tend to forget are shared by others – to his later days as a highly sought-after artist travelling the world and working on large projects in Europe.

An entry from April 29, 1977 reads: “This is a blue moment . . . it’s blue because I’m confused, again; or should I say “still”? I don’t know what I want or how to get it. I act like I know what I want, and I appear to be going after it—fast, but I don’t, when it comes down to it, even know. I guess it’s because I’m afraid. Afraid I’m wrong. And I guess I’m afraid I’m wrong, because I constantly relate myself to other people, other experiences, other ideas. I should be looking at both in perspective, not comparing. I relate my life to an idea or an example that is some entirely different life. I should be relating it to my life only in the sense that each has good and bad facets. Each is separate. The only way the other attained enough merit, making it worthy of my admiration, or long to copy it is by taking chances, taking it in its own way.”

The Keith Haring Foundation has scanned all of Haring’s journals from 1971 to 1989, the year before his death. The pages from his journals can be read on this Tumblr account, set up by the Foundation.

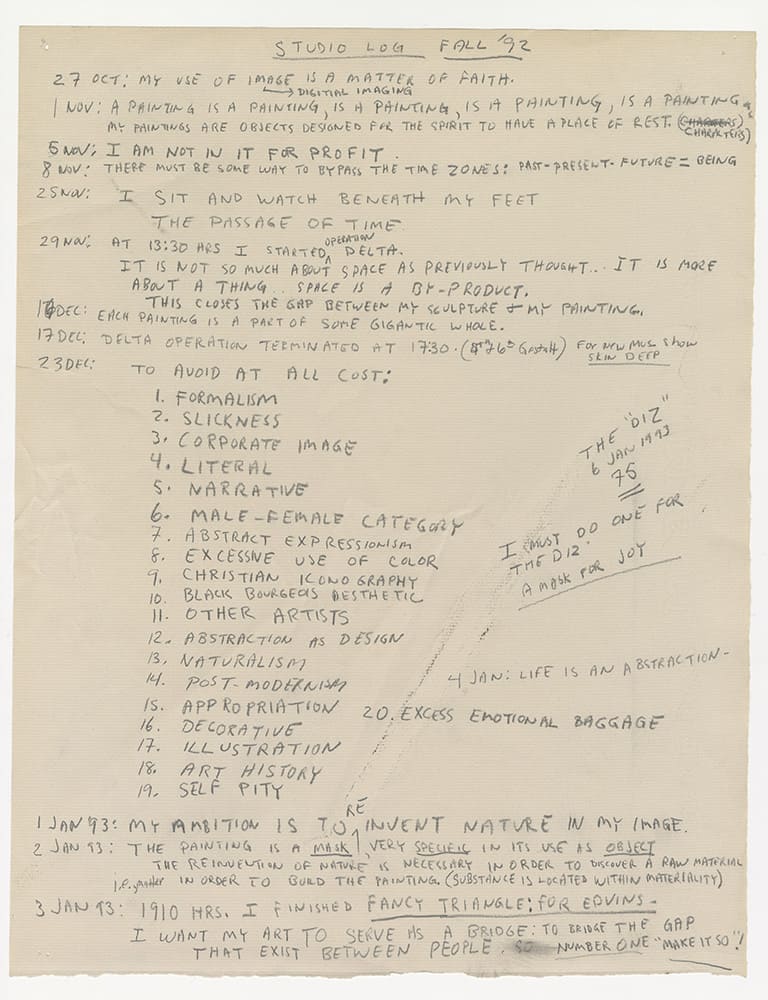

5. Jack Whitten’s Diaries

Jack Whitten was the only African American artist to be part of the first generation of Abstract Expressionist artists. Lewis became known for his innovative painting processes, with which he transfigured the material terrains of his canvases. Throughout his life, Whitten struggled to transcend the sociopolitical structures that he felt trapped in with his art. He ached to create art that was unburdened by social restrictions and believed that abstraction was the way to achieve this. The evolution of his artistic style and his struggles and breakthroughs are all documented in his moving diaries, or “studio notes,” as he called them himself, spanning the course of his five-decade-long career. From crippling insecurities to confidence as he explores new terrains, Whitten’s studio notes reveal an inspiring and brave artist who always managed to find a way to continue. In December 1985, a desperate entry reads: “I am black, 46 years old, angry, tired of teaching, tired of being poor[…] What am I to do?” In September 1994, Whitten writes: “No Religion, No Politics, No sex, No Autobiographical Pretense, or Historical References, No Identities whatsoever, No commerce or Market ideologies. I WANT ART.” In another entry he proudly describes his sense of innovation in art: “To my knowledge no one has arrived at an image by using a flooring chisel to chip away paint…. no one has used a carpenter’s saw either or a shoe shine brush or an afro comb, or a plumber’s plunger… Maybe I’ve been doing something new all along without knowing it.”

In 2018, Hauser & Wirth Gallery published Notes From the Woodshed, a publication devoted to Whitten’s extensive journal entries or studio notes. The artist’s dedicated personal studio notes, which he initially refused to publish and reveal to the public but finally decided to share, offer an invaluable insight into how Whitten developed and fought for his art until the very end.

Relevant sources to learn more

Find the publications of these artist diaries here:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Arundel

Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus