Articles and Features

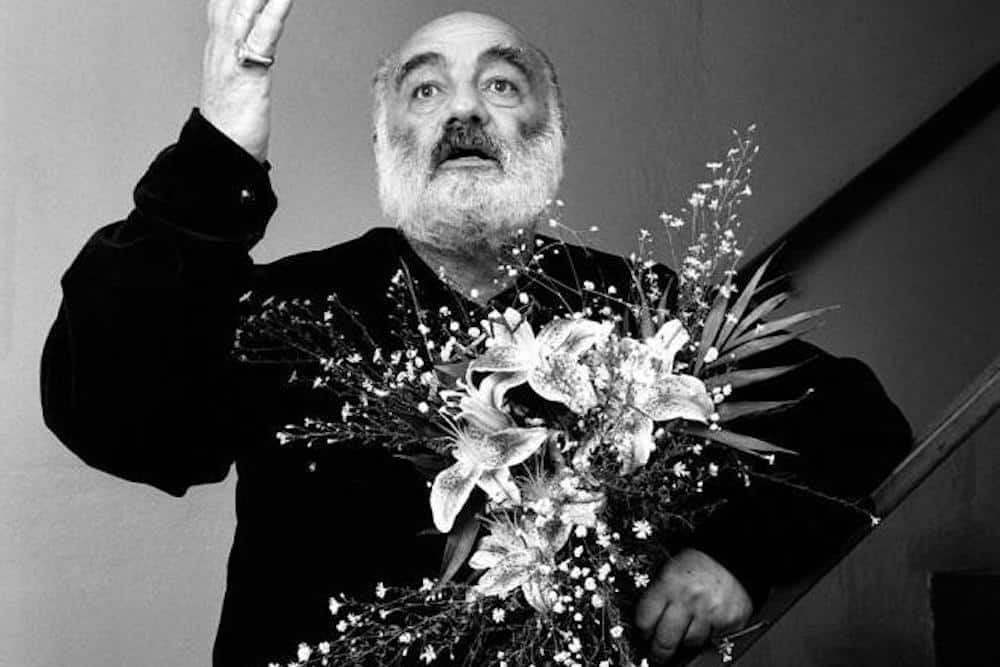

The Other Sergei Parajanov: The Collages of the Magician of Cinema

By Shira Wolfe

“In the temple of cinema there are images, light and reality. Sergei Parajanov was the master of that temple.” – Jean Luc Godard

In this article series, we explore the lesser-known output of artists who became famous for another medium or genre of art. Often, great artists wear many different hats, but break through and achieve acclaim because of their work in one specific medium. We aim to highlight the multifaceted nature of their talent by shining a light not on what they are best known for, but on the lesser-known side of their artistic production. Sergei Parajanov was an Armenian filmmaker who was raised in Tbilisi in the Republic of Georgia, then part of the Soviet Union. He is known as one of the great masters of cinema whose two masterpieces, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors (1964) and The Color of Pomegranates (1969) made him admired and beloved by some of the greats in cinema, including Fellini, Godard and Tarkovsky. Parajanov was imprisoned three times on account of his homosexuality, making movies that the Soviet regime found questionable, and speaking out against the regime. It was during his time in prison that the great filmmaker turned to making collages, as well as drawings, card games and photomontages. He continued making visual art during the long period of 15 years when he was banned from making movies. The artworks carry the unmistakable quality of Parajanov’s vision and aesthetic – they are his distinctive reaction to the world around him.

Sergei Parajanov’s Cinema

Sergei Parajanov was born in 1924 to Armenian parents in Tbilisi, Georgia, which was then part of the Soviet Union. He graduated from the world’s oldest film school, the Institute of Cinema (V.G.I.K) in Moscow, in 1951. Parajanov created his first masterpiece, Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, in 1964 in Ukraine. The film, which was based on the book by Ukrainian author Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, portrays Ukrainian Hutsul culture, an ethnic group living in parts of Western Ukraine and Romania. Parajanov earned international acclaim for his rich use of symbolism, colour and costume in the film. However, the Soviet authorities blacklisted him for his movie’s support of Ukrainian dissidents and nationalists, jeopardizing all further projects in Ukraine. He was blocked from finishing his film Kyiv Frescoes (1966), which was meant to portray the aftermath of WWII in Kyiv, and the authorities destroyed all his negatives. Only parts of the footage remain.

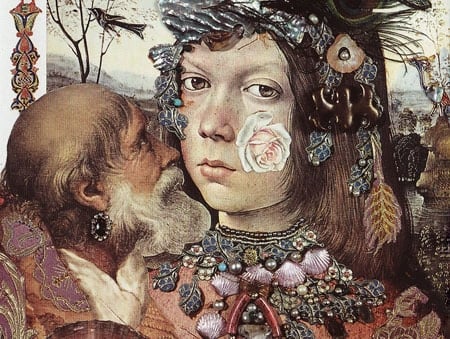

Parajanov next moved to his ancestral homeland, Armenia, in order to work on a new project, which was to become his most groundbreaking film: Sayat Nova or The Color of Pomegranates (1969). The film reveals the life of Armenian poet Sayat Nova, but through the unique and abstracted imagination of Parajanov who created images inspired by Sayat Nova’s life and poems. The Color of Pomegranates is like a collection of paintings. Deeply inspired by Turkish, Iranian and Armenian miniatures found in books, Parajanov set out to create an evocative and abstract film composed of different frames with barely any movement, just like the miniatures. And just as when you look at a miniature and begin to create movement in the image with your own eyes, Parajanov inspired a similar dialogue between stillness and movement, film and viewer. In his words: “Sayat Nova is different from the previous films. The religious Armenian miniatures, that by their motionlessness create spirituality and poetry, awoke in me a strange veneration. I have the same preconception of this film. I know that dynamic cinema is the very idea of cinema. Motionlessness is seen as weakness or fatigue. Yet it is just the opposite! It’s passion! Creating a dynamic in the motionlessness.” Despite the success of the movie, Soviet censors took issue with it and re-cut it, and Soviet movie studios rejected all his projects after The Color of Pomegranates. Parajanov criticized the state of Soviet cinema and the authorities during a speech in Minsk, Belarus, and was sentenced to 5 years in a Ukrainian prison in 1974.

“In prison, completely isolated, I did the crying Mona Lisa. A collage. She’s expressing her pain if I were to die in prison. This is how I supported four years and eleven days, by creating a collage each day. I made about 800 works of art.” – Sergei Parajanov

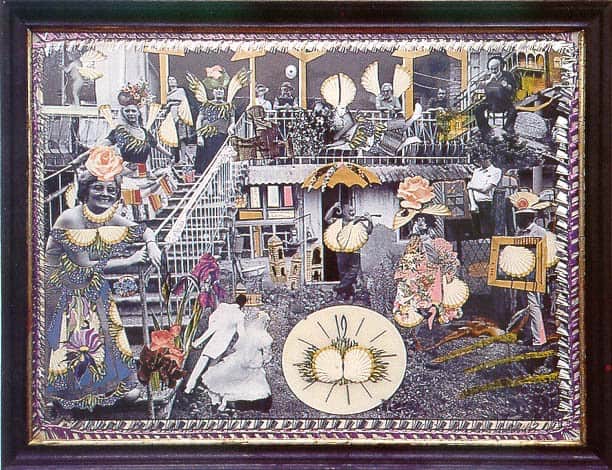

Sergei Parajanov’s Visual Art in Prison and Beyond

In prison, unable to make movies, Parajanov first turned to visual art, in particular collage. Of this period, he said: “In prison, completely isolated, I did the crying Mona Lisa. A collage. She’s expressing her pain if I were to die in prison. This is how I supported four years and eleven days, by creating a collage each day. I made about 800 works of art.” After a wave of protests against Parajanov’s imprisonment from artists around the world, including François Truffaut, Luis Buñuel, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Michelangelo Antonioni and his close friend and collaborator Mikhail Vartanov, a direct petition from Louis Aragon to the Soviet leader Brezhnev finally led to Parajanov being released from prison in 1977. He had been locked up for three years. He returned to Tbilisi, Georgia, where he was imprisoned again in 1982 for ten months. As he was blocked from working in cinema since The Color of Pomegranates and his arrest, Parajanov poured his creative vision into his collages, drawings, card games, photomontages, dolls and even hats inspired by characters from books and movies (Anna Karenina, My Fair Lady etc.) for 15 years. French-Turkish conceptual artist Sarkis, a great admirer of Parajanov’s, has said: “Had he been able to film in permanence, I’m not so sure he would have made all of these objects. It’s like it was a dream to make the images he wasn’t able to film. I think they’re like sketches, waiting to be animated.”

For his collages and assemblages, Parajanov would frequently look in dumpsters for objects to incorporate in his works. This was something he had always done, even when working on his movies and creating the costumes. “Covetousness was born in me. A desire to possess, then to create,” he said. He was bewildered by filmmakers who would send for expensive costumes from Paris for their movies, when they could find a treasure-trove of materials and objects closer to home, and even among other people’s discarded items. Parajanov’s collages open another window into the great mind and creative vision of Parajanov – they are like stills or actors from his unrealized movies. Without salary or income, blocked from his preferred artistic medium for 15 years, Parajanov found a way to persevere and to continue to create, no matter what constrictions and adversity he faced. He even managed to find pockets of hope and positivity in his difficult situation. For example, when speaking about living in poor conditions with a constantly leaking roof, he once noted how the cracks in the roof and the constant leakage reminded him of Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia, and that all his colleagues were envious because of this.

In 1984, Parajanov was finally permitted to direct again, and continued working with his characteristic passion and vision until he was hospitalized in 1989, and passed away in 1990, leaving behind some of the most stunning visual imagery of the 20th century. A large collection of his visual art can be seen at the Parajanov Museum in Yerevan, Armenia.

Relevant sources to learn more

Sergei Parajanov: The Rebel (documentary about Sergei Parajanov)