Articles and Features

Subtracting Reality, Revealing Beauty. A Tribute To The Unique Legacy of Christo and Jeanne-Claude

“I think it takes much greater courage to create things to be gone than to create things that will remain”.

Christo

Who are Christo and Jeanne-Claude?

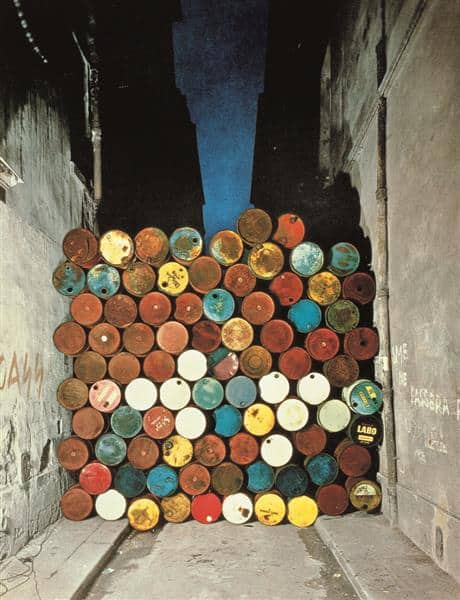

If you happen to visit Paris, you might want to stop by Rue Visconti. Connecting Rue Bonaparte and Rue de Seine, it is one of the narrowest streets in the city and, since the sixteenth century, has been home to many prestigious tenants, including Racine, Delacroix, and Balzac. However, the fame of this little street famous was premised not on its illustrious inhabitants nor its historic boutiques, but instead an event of June 27th, 1962. It was 9 pm when, in front of a small dumbfounded crowd, a truck entered the street, stopped and unloaded 89 metal barrels used for transporting gasoline and oil. What at first glance could be mistaken for a public works crew at this unusual time of day was actually the first large-scale work by a couple of artists that would literally come to spread their vision over much of the world.

The barrels, not altered in any way from their original industrial appearance – colours, brand names, and rust were still visible – were arranged to form an impassable, four-meters-high barricade that blocked the street for eight hours. The artwork, titled Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain, temporarily transformed the perception of Rue Visconti turning it into a dead-end street: a simple action full of implications by which the artists, Christo Vladimirov Javacheff and Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon – at the time working just under the name “Christo” – manifested their protest against the recent construction of the Berlin Wall.

The previous year, the artistic duo had applied to the municipality of Paris for permission to create the work, a request that had been denied; therefore Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain proved to be a foretaste not only in terms of their approach to urban intervention and medium – cans and barrels will be recurrent in Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work – but also in terms of their exceptional tenacity in realising their projects.

Last week, Christo passed away in his home in New York City at the age of 84, having outlived his life and work partner, Jeanne-Claude, by eleven years. His studio stated: “Christo lived his life to the fullest, not only dreaming up what seemed impossible but realizing it. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artwork brought people together in shared experiences across the globe, and their work lives on in our hearts and memories”.

Their extraordinarily influential work reshaped and exalted reality by removing obviousness and habit from the world’s eyes, permanently changing our perception of urban and natural surroundings, influencing the parameters of art, sculpture, installation, land and environmental art, and expanding the very definition of contemporary art itself.

“We want to create works of art of joy and beauty, which we will build because we believe it will be beautiful”.

Jeanne-Claude

Biography of Christo

Christo was born in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, in 1935 and grew up amid the wreckage caused first by the First Balkan War, and then by the carnage of World War II. He was educated under the repression of the postwar communist regime, choosing at the age of 21 to pack up his things, and to make this way westwards via Prague, then Vienna, Geneva and, by 1958, in Paris. With no money, no connections and not a word of French, Christo began to do every kind of job imaginable to earn a living–repairing cars, washing dishes in restaurants, carrying crates of tomatoes and, most of all, painting portraits which he signed by his family name: Javacheff. On one occasion he was commissioned to portrait the wife of General de Guillebon, Précilda: she was Jeanne-Claude’s mother. Born on the exact same day, the 13th of June, 1935, Jeanne-Claude and Christo fell in love, and in no time were married.

Story of an iconic duo: Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s enduring artistic collaboration was also to begin, and the couple seemed to have a clear and determined plan; in a 1958 letter, Christo wrote: “Beauty, science, and art will always triumph”.

Whist at the time it was their purpose and strategy, today it forms the bedrock of their legacy.

They began with wrapping objects, small everyday items such as bottles and cans packed in fabric or synthetic materials and twine, largely inspired by the work of Joseph Beuys and Man Ray, especially L’Enigme d’Isidore Ducasse. The idea behind the wrapping was that the concealment encourages the viewer to look with renewed curiosity to the object beneath and the space in which it exists, whilst also adding new sculptural qualities to ordinary shapes.

After Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain, the duo officially stepped into the art world.

In 1964, they moved to New York bringing the intent and act of wrapping to a much vaster scale, applying it to both natural and man-made environments and refining a technique that was to become a signature and artistic trademark.

They started in 1968, first wrapping a fountain and a medieval tower in Spoleto, Italy, followed by the Kunsthalle in Bern, and moving onto the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, with this early period culminating in wrapping a one-million-square-feet portion of coastline in Little Bay, Sydney. These endeavours were followed by two historical monuments in Milan, part of the Aurelian Wall in Rome and, among their most iconic projects, The Pont Neuf in Paris and the Reichstag in Berlin, respectively in 1985 and 1995.

The latter was one of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s most grandiose undertakings, not only involving 100,000 square metres of silvery fabric, almost ten miles of blue rope, the labour of around two hundred professional climbers and installation workers, but also twenty-four years of parliamentary debate. The building was symbolic of tradition and nationalism, but also problematically associated with the rise of Nazism: it was meant to be wrapped and then unwrapped in an act of national renewal. The artists had conceived the idea in 1971 but then had to negotiate with six different Chancellors to create a work of stunning complexity, but also fleeting ephemerality since it remained in place for only two weeks.

But Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work was not all about “wrapping”. If a common denominator is to be found, it is in the use of simple objects, fabric, the breathtaking mediation between nature and human intervention, and the temporality of these extraordinary transformations.

For the project Valley Curtain (1972), they installed an orange curtain made of woven nylon fabric between two Colorado mountain slopes – the work only lasted twenty-eight hours since a wind-storm made it necessary to remove it. Then came Running Fence, a series of white fabric panels snaking their way over ranchland in Northern California to the ocean.

In 2005, they plotted pathways through New York’s Central Park with thousands of monumental saffron-curtained gates, whilst their last realised work, from 2016, was a shimmering yellow walkway, floating on the surface of Lake Iseo in Italy. Over one million visitors who enjoyed the piece for the sixteen days of its existence could attest to its stunning success, literally walking on water.

Conceptual or Land artists?

Christo and Jeanne-Claude have often been defined as Conceptual artists or Land artists, though they resisted such categorisations: “We believe that labels are important, but mostly for bottles of wine”. In the former case, they refused the association claiming that whilst Conceptual Art could potentially exist without being realised, the essence of their work lay instead in the fulfilment of its physical manifestation, bringing joy and wonder through the accessibility of the art, but also through the tribulations of the process needed to come to such fruition: “For me, aesthetics is everything involved in the process — the workers, the politics, the negotiations, the construction difficulty, the dealings with hundreds of people (…). That’s what I’m interested in, discovering the process. I put myself in dialogue with other people”.

In the latter case, they resisted the ‘Land Art’ definition since they never worked in remote or deserted places, but always in locations relevant to, and used by, vibrant populations.

Transience was vital to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artistic research, it gave their work the aura of a myth that only impermanence can bestow: “We never let a work exist for more than two weeks. If you don’t see it, you don’t see it. We will never make another floating pier, never place another curtain across a canyon – and we will never wrap another parliament”.

They frequently used to declare that their work had no deeper meaning than its ephemeral aesthetics with its only true purpose to create joy, beauty, and new ways of seeing: “I make things that have no function – except maybe to make pleasure”. Nevertheless, a political connotation seemed often to be implied – albeit downplayed by the artists themselves. One only has to return to the beginning of their remarkable sequence and the Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain to identify this inescapable facet. In 2017, Christo decided to abandon a long-planned work, Over the River: a proposed almost six miles of silver fabric erected as a canopy over the Arkansas River in Colorado for two weeks; it would have been Christo’s largest work in America, to be realised at a cost of around $50 million. The reason behind the cancellation? The terrain’s new landlord. Since it was federally owned, the landlord happened to be the newly elected President Trump, whose administration the artist did not want to have anything to do with: “And here now, the federal government is our landlord. They own the land. I can’t do a project that benefits this landlord. (…) The decision speaks for itself”.

A new way to support Art: Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s business model

The search for freedom that led Christo to escape from his native country as a young man endured across the decades, indissolubly permeating his art. In order for their work to achieve the desired state of unconditional purity and freedom, Christo and Jeanne-Claude never accepted commissions, grants, scholarships, donations or public money of any kind, nor any sponsorships or commercial agreements: “We always rent at least 1 km around the site, so no one can use our work as a backdrop for commercial purposes. It has to stay pure”. In 1988, they refused a one million dollar fee for a one minute commercial on Japanese television. They never collaborated with other artists, nor took suggestions or proposals. The duo did not have royalties either on the books and films about their works, instead they often financially helped – at times entirely funding – the publication of books as well as the making of documentaries.

Along with freedom, Christo and Jeanne-Claude greatly valued the democratic aspect of their projects, trying to involve as many potential collaborators as possible, and across the gamut of human output including engineers, rock-climbers, fabric makers, politicians and many others. Notions of freedom crucially also extended to the liberty of the public to consume and absorb their spectacular creations; admission fees were never charged, all of their works had to been enjoyed for free.

Clearly, their projects were not inexpensive to realise. For instance, the Wrapped Reichstag in 1995, cost $15.3 million. How was possible to reconcile the largesse of their ideas with the enormous expense of making them? How did they pay for the seemingly endless need for engineers, attorneys, consultants and professional services of all stripes, but also materials, shipping, insurance, rentals and so forth? Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s art may have been itself revolutionary, but no less innovative was their way of operating and funding. They managed to pay for the entirety of each of their projects themselves, latterly by selling valuable early works from the fifties and sixties, but always by selling preparatory drawings, collages, and scale models of the very projects themselves. Whilst all works were conceived, ideated and realised by both Christo and Jeanne-Claude, it was only Christo who committed the ideas to paper. These preparatory materials unveil the evolution of their ideas and a clear rendering of vision, beautiful discrete works unto themselves, but, as importantly a currency to pay the accumulated expenses pertaining to organisation, realisation, maintenance, and disassembly of the works.

This unprecedented business model assured the couple total freedom and independence: they chose what to do, how to do it, and where to do it, assuming the co-operation of the relevant authorities as demonstrated by the 24 year hiatus between conception of the Wrapped Reichstag and its ultimate fulfilment.

L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped

Years ago, when asked during an interview about retirement Jeanne-Claude said “Artists don’t retire. They die. That’s all. When they stop being able to create art, they die”. Both she and her husband have lived this maxim, creating until the very end of their respective lives.

However, it is not entirely the case that they have stopped creating art: the monumental installation L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped, will be created posthumously next year in Paris, in accordance with the wishes of the artist. The project was planned for Fall of 2020 but had been postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic; it will be in situ for sixteen days starting from the 18th of September 2021 and, it goes without saying, will be free of charge to an enthralled public. Like with all their major public installations it will no doubt let us see the world with childlike wonder, and in the process both change our existing perceptions of the world that surrounds us, and demonstrate the power the power of patience, perseverance, and relentless determination.

At the same time, a major exhibition will be presented at the Centre Georges Pompidou, devoted to Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s years in Paris, ending their story where it began almost sixty years ago.

Relevant sources to learn more

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Website

List of films and documentaries about Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s work

Stories of Iconic Artworks: Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s Surrounded Islands