Articles and Features

Reimagining Spaces with Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative

By Adam Hencz

“A key part of everything we did was to make the language and practice of architecture more transparent and accessible to non-experts.”

Dr Jos Boys

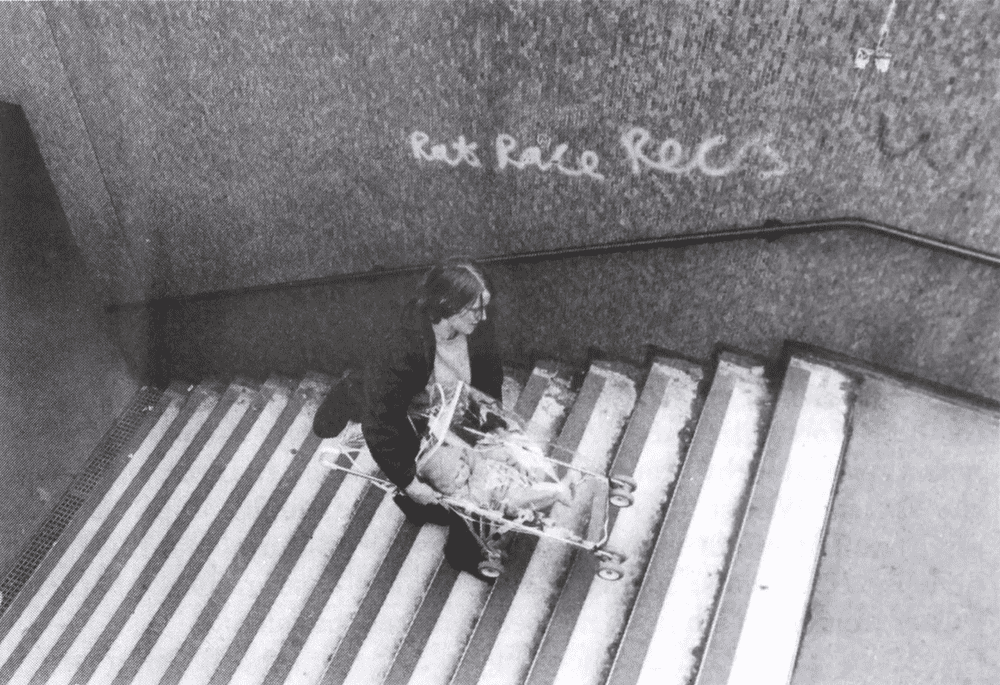

How have women’s empowerment and feminist activities challenged our built surroundings? How might architecture be conceived differently and with a greater focus on inclusion? How would a city designed and built collectively be different? How We Live Now: Reimagining Spaces with Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative, a new installation at Barbican Centre’s Level G debates these questions about our public spaces and designed environments, and discusses who they serve in the first place, and what effect they have on the communities who inhabit them. Central to the exhibition is an extended, unseen archive of works by the 1980s feminist architecture co-operative Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative, one of the first to explicitly call itself “feminist,” that aimed to subvert design conventions and gender stereotypes with a critical and inclusive architectural practice while exploring relationships between gender and architecture.

How We Lived Then

From the early 20th century, working-class women increasingly voted with their feet to leave domestic employment as the production and sale of new household appliances supported the shift of middle-class women taking over their household’s domestic labour. What is known as the professionalisation of housework, from the 1920s saw kitchens modelled on laboratories, with worktops to stand at, facing the wall, and ergonomically arranged storage spaces. Meanwhile, the boom in suburban developments left many women isolated at home.

Feminists and many other groups since then have been unravelling dated stereotypes about what different people do and how they should behave as well as analysing the effects of these ideas on the design of our built spaces.

In the late ‘70s, a group of women involved in the New Architecture Movement in London began meeting separately to discuss feminist perspectives and specific issues women faced in built environments. A few years later, they would establish the Feminist Design Collective, a group that campaigned for the increase in the number of women going into the architectural profession, and challenged conventional design practices in order to enable women to influence the design of built space.

Matrix was an organisation that split from the Feminist Design Collective and became one of the first and most successful architectural associations worldwide to bring a feminist approach to architecture, as well as one of the first women-led architectural practices. In a manifesto written at its inception in 1981, founders of the Matrix wrote: “Consciously or otherwise, designers work in accordance with a set of ideas about how society operates, who or what is valued, who does what and who goes where. Through lived experience, women have a different perspective of their environment from the men who created it. Because there is no ‘women’s tradition’ in building design, we want to explore the new possibilities that the recent change in women’s lives and expectations have opened up.”

Architectural practice

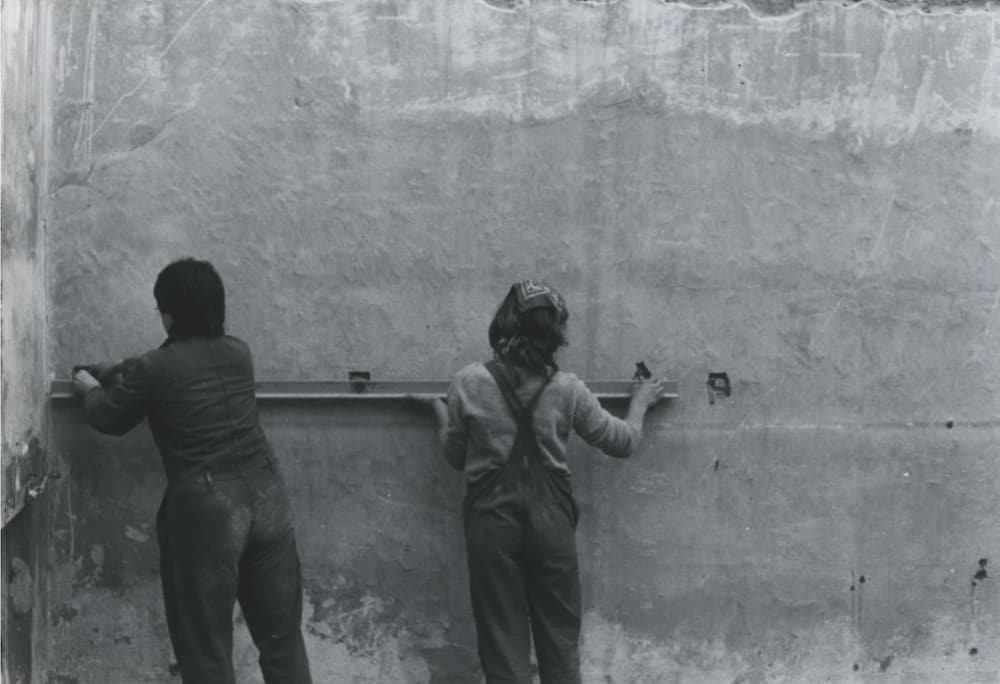

Matrix was often asked what feminist architecture looks like. Speaking to the Guardian about the Barbican installation, Dr Jos Boys, a founder member of Matrix, who curated the exhibition with Jon Astbury from the Barbican Centre, said that rather than promoting a feminist aesthetic, Matrix always favoured a way of looking, listening and designing that took account of people’s different needs and desires, in other words, “the richness of our multiple ways of being in the world”. One of Matrix’s most important principles was to experiment with collaborative ways of working with people, groups and organisations that were traditionally excluded from architectural design processes. This practice aimed at making design processes —such as architectural planning methods and drawing techniques— more understandable to women’s and community groups so that they would have a real say in what building projects should be like.

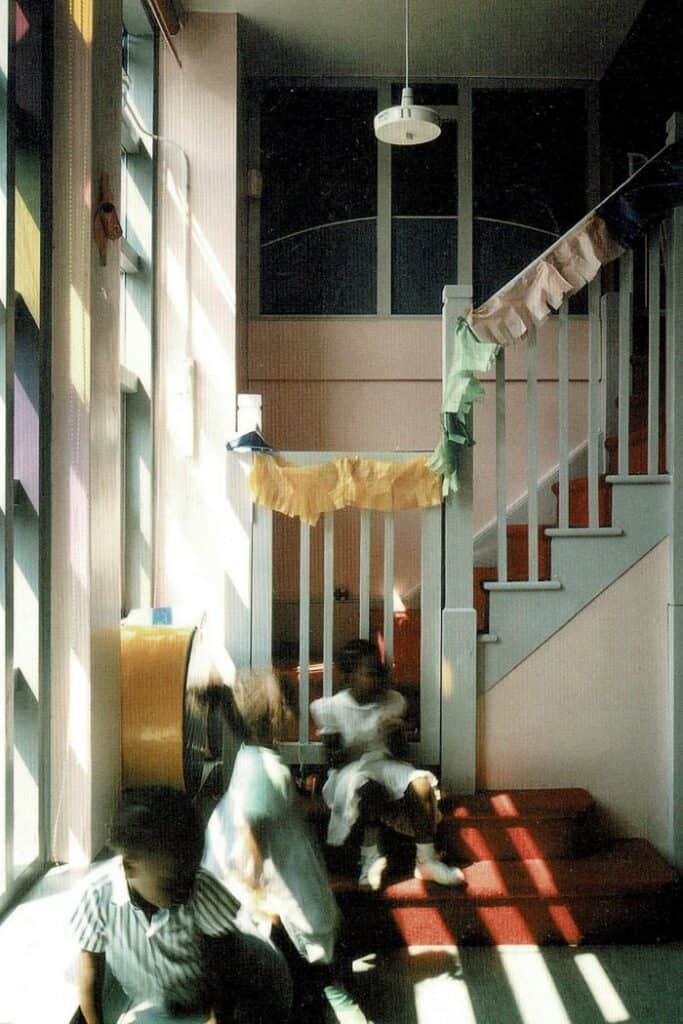

This principle resulted in ambitious new buildings that had not existed before — not just alternative forms of housing but also women’s centres, workshops, refuges and alternative childcare facilities. Their projects included the groundbreaking Jagonari Asian Women’s Centre in Whitechapel, east London. The isolation felt by many immigrants around the late 1970s led to establishing their own clubs and institutions, so the educational centre became Matrix’ first big project. ‘Described as a ‘hybrid, syncretic architectural space, built out of London brick and containing a mosque-inspired courtyard and South-Asian style decorated window grilles and railings’, the centre took its name from the poem ‘Jago Nari Jago Banhishikha’ by Nazrul Islam, meaning ‘Women Awake’, or ‘Rise Up, Women’.

Another innovative project work by Matrix was the redesign of the Essex Women’s Refuge Centre, a complex that was originally built in a way that did not take into consideration its future habitants needs and its social function, thus creating futile and imbalanced spaces. Carelessness about details would lead to serious design flaws especially in community-based projects. Conventional relationships between architectural firms and clients often reflected a one-sided decision-making process and a strictly controlled development practice, which in the case of the Women’s Refugee Council in Essex for example resulted in the creation of children’s play areas that were sealed off of main communal areas, therefore making passive adult supervision impossible. Matrix tried to overcome the isolation of clients and community members from the design process and aimed at breaking down the status differences between design and actual building work. This was also a novel approach to the role of the architect as well moving from offering ready-made designs towards participatory design methods in all stages of the evolution of the building.

“These were all simple techniques,” Dr Boys told in an interview on the occasion of the ongoing exhibition. “But they made the women feel part of creating the project. A key part of everything we did was to make the language and practice of architecture more transparent and accessible to non-experts.”

The Legacy of Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative

Although much of what Matrix worked on was funded by the Greater London Council, Matrix itself did not survive the political and economic shifts of the Thatcher era, ultimately closing in 1994. Matrix has had an ongoing impact on feminist approaches to design and participatory design methodologies, and is an important precursor to later feminist groups and organisations, particularly in recent years as both students and academia have rediscovered their work. The demand is so high that Matrix’s seminal 1984 book, Making Space: Women and the Man Made Environment is long out of print and is to be republished later this year.

The impact of the collective was reinforced institutionally as well in 2019 when Matrix was first nominated for the RIBA Gold Medal Award. In 2020, the Matrix Open Feminist Architecture Archive (MOfaa) project received seed funding from the University College London Bartlett Innovation Fund to develop an online resource.

Relevant sources to learn more

Matrix Open Feminist Architecture Archive (MOfaa)

How We Live Now: Reimagining Spaces with Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative