Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: María Izquierdo

By Shira Wolfe

“María Izquierdo represented Mexicanness better than Frida Kahlo, not in her folklore but in her essence.”

Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska

An Outsider’s Winding Journey

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their careers. This week, we feature Mexican artist María Izquierdo (1902-1955). Once defined by Diego Rivera as “classically Mexican” both in her personality and her painting, she gradually distanced herself from the then overriding style of the great Mexican muralists, for whom painting was above all a political tool. Together with artist Rufino Tamayo, she explored other influences from abroad such as Picasso, Gauguin and de Chirico. This eventually led to her being pushed out of the art establishment, to the point of losing commissions since Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros had argued she was too inexperienced. She was all but forgotten until the 1970s, and a 1997 retrospective at the Americas Society in New York helped confirm her place in the history of 20th-century Mexican art.

María Izquierdo – Classically Mexican

María Izquierdo was born in San Juan de Los Lagos in 1902, at the time a rural environment deeply attached to 19th-century Mexican Métis traditions. She was raised by her maternal grandparents, who pushed her to marry a soldier at just 14 years old. She had three children with him in rapid succession but was deeply unsatisfied with this life as a wife and mother. When the family moved to Mexico City in 1923, Izquierdo had the opportunity to attend classes in painting and sculpture. In 1926, she left her husband and distanced herself from her maternal family, suddenly finding herself alone with her three children in Mexico City. This radical break allowed Izquierdo to pursue what she really wanted: to be an artist. She enrolled at the prestigious San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts and studied there from 1927 to 1928. During her brief time at the Academy, Izquierdo met the artist Rufino Tamayo, who became her lover, and Diego Rivera, who became her mentor. Deeply impressed by her, Rivera wrote: “Her personality is like her painting: classically Mexican.”

Both Tamayo and Rivera had a profound influence on Izquierdo’s life and art. She studied watercolour and gouache with Tamayo and was given her first important exhibition at the Galeria de Art Moderno in Mexico City in 1929 thanks to Rivera. Her studies at the Academy, however, had come to an abrupt halt in 1928. The other students were infuriated at Rivera’s special attention for Izquierdo’s work and she was tormented by envious students, forcing her to leave school. Shortly after, Rivera himself was fired.

Developing her Artistic Style

Izquierdo moved in with Tamayo and lived with him for four years. It was during this period together that she truly discovered her own style. The couple shared a very intimate approach to painting, and Tamayo taught Izquierdo techniques suited to small formats. They took inspiration from European avant-garde artists at a time when not many Mexican artists were looking towards European artists for inspiration. This gradually distanced them from the great Mexican muralists Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco, who only accepted painting as a political tool for achieving “Mexicanness”. In this period, Izquierdo was also experiencing Mexico’s national reawakening rooted in previously suppressed pre-Columbian art, crafts and folklore. She started learning more about the painterly value of objects and started wearing clothing associated with Mexico’s Indigenous communities, asserting the integral role of these Indigenous cultures in Mexico’s new national identity after the revolution of 1910-20. She shared this tendency with other female artists of the time such as Frida Kahlo, Tina Modotti, Maria Asunsolo and Lola Alvarez Bravo.

“All of her paintings are in this colour of cold lava, as if in the semidarkness of a volcano.”

Antonin Artaud

Subjects and Themes

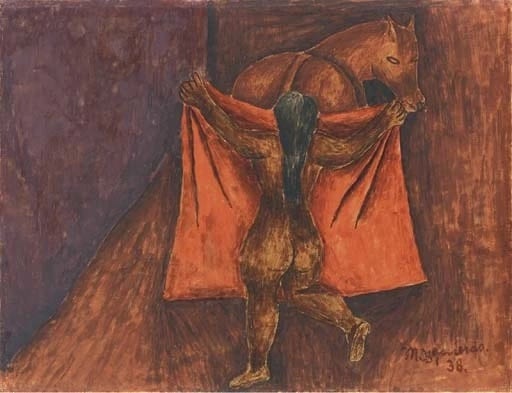

Izquierdo focused on several chosen subjects: village circuses, peaceful horses, still lifes, self-portraits, and portraits. In her self-portraits, she highlighted her Indigenous features by portraying herself wearing the traditional ornaments she would wear in her everyday life. This was her personal resistance to the country’s accelerated urbanisation, which often relegated traditional clothing to the rank of costume. Izquierdo’s self-portraits show her taking a strong position as a woman of her contemporary time and place who wished to highlight the importance of traditional Indigenous culture. This set her apart from the general cultural production of the Mexican art world, which was mainly driven by nationalist and political interests.

The theme of the circus gave Izquierdo the opportunity to depict a microcosm she was fascinated by, due to its formal existence on the margins of history. In her still lifes, she focused on the theatrical representation of religious subjects in colonial art. She mixed everyday objects with images evoking religious figures.

International Acclaim

International acclaim came in 1936, when the surrealist French poet, writer, actor and theatre director Antonin Artaud discovered her work during his stay in Mexico. Her paintings in the 1930s were dominated by an earthy palette and Artaud wrote in a Paris monthly review that “all of her paintings are in this colour of cold lava, as if in the semidarkness of a volcano.” Although the eccentric Frenchman’s enthusiasm somewhat subsided when he identified the influence of modern European art in her work, he returned to Paris with some of her watercolours and Izquierdo received a show in Paris, which was a great success. Meanwhile, Izquierdo had already been the first Mexican woman to exhibit in the United States, in 1930. After her Paris show, Izquierdo showed in San Francisco, and then at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in a group show. At a subsequent exhibition at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, she was hailed as the best contemporary Mexican painter.

In 1944, Izquierdo married a Chilean diplomat and travelled to Chile as an ambassador of Mexican arts. There, she was received by her old friend Pablo Neruda, who wrote a tribute for her exhibition there. This was the peak of her career.

Blocked to work by Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros

Following a triumphant trip to South America in 1945, where Izquierdo was welcomed as a hero by the political and artistic elite, she returned to a great disappointment back in Mexico. She discovered that the fresco she was meant to paint at the Mexico City Hall had been cancelled. The reason: Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros had argued that this type of work was beyond the capabilities of an artist with no experience in muralism. The man who had once been her mentor and greatest supporter had now truly turned against her, blocking her from an important commission. From this point on, Izquierdo’s artistic life became more difficult and when she denounced the two great muralists in public, only a few people supported her, receiving a great deal of criticism instead.

In this period, Izquierdo started to have intense nightmares that foreshadowed trouble in her future. She sometimes painted what she remembered from these nightmares. In 1947, she painted Sueños y Pensamento, a painting that depicts her nightmare: the artist is holding her own decapitated head, while her headless body walks past tree branches from which dangle other severed heads. The nightmare and painting predicted great pain in her future. In 1948, Izquierdo suffered a stroke and was left paralysed on the right side of her body. Through an incredible effort of willpower, she trained her left hand in order to be able to continue to paint. Although she managed to paint 20 more works before she died in Mexico City in 1955, she was never able to paint the same quality of work as before the paralysis.

Rediscovery

In 1997, the first retrospective of Izquierdo’s art was held in New York City, and since then her work has appeared in numerous shows in the US and Canada. On 25 October 2002, 100 years after her birth, Izquierdo was declared a ‘Monumento Artistico de la Nación’ by Mexico City’s National Commission for Arts and Culture. This ensures that her work will be protected, catalogued, studied and conserved, thus preserving her legacy as one of the great Mexican artists of her time. In recent years, there has been a renewed interest in Izquierdo’s art and she was included in the 2020 exhibition “Vida Americana” at the Whitney Museum of American Art, which examined Mexican Modernism from 1925-1945.

Although she suffered from exclusion in the art world during her lifetime due to envy and misogyny, Izquierdo made a significant mark on the history of art throughout her relatively short life. Now she is receiving a well-deserved reexamination.

Relevant sources to learn more

AWARE: Archive of Women Artists Research & Exhibitions

Cultura Colectiva

Vida Americana: Whitney Museum of American Art