Articles and Features

The Other Pasolini: The Drawings and Paintings of the Great Film Director

By Shira Wolfe

“The thought of doing anything traditional makes me nauseous.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini

This article series explores the lesser-known artistic output of artists who became famous for another medium or genre of art. Often, great artists wear many different hats, but break through and achieve acclaim because of their work in one specific medium. We aim to highlight the multifaceted nature of their talent by shining a light not on what they are best known for, but on the lesser-known side of their artistic production.

Pier Paolo Pasolini was one of 20th century Europe’s leading intellectuals, known for his subversive work as a film director, poet, and writer. He spoke out against government corruption, materialism, consumerism, and political and social repression and was notoriously averse to anything traditional. He also foresaw and opposed the way Italy and the rest of the Western world were heading towards a uniform, universal, standardised society, even before the idea of globalisation became widespread. He left a permanent mark on culture and society all over the world with his controversial films such as Accatone (1961), Salò (Salò, or the 120 days of Sodom) from 1975, Teorama (1968), and Edipo re (1967). What is less well known about Pasolini is the fact that he made visual art. When it came to painting and drawing, Pasolini was a self-professed dilettante, yet taking a longer look at his paintings and drawings reveals a talented draftsman who infused his visual art with that same raw passion and depth that we find in his films.

Pier Paolo Pasolini – A Poet Becomes a Director

Pier Paolo Pasolini was born in 1922 in Bologna, Italy. As he was the son of a lieutenant in the Royal Italian Army, the family moved frequently. Pasolini started writing poems at the age of seven, inspired by the natural beauty of Casarsa della Delizia, his mother’s family home in the Friuli region where they lived for a period. The constant moving was difficult for Pasolini, but he did get to expand his knowledge of poetry and literature. One of his earliest influences was the poet Arthur Rimbaud, and he eagerly read works by Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Shakespeare, Coleridge, and Novalis.

During the ’20s, Pasolini’s father became persuaded of the virtues of Fascism, and during his studies at the University of Bologna, which he commenced in 1939, Pasolini participated in the Fascist regime’s culture and sports competitions. His poems of the period started to include fragments in Friulan, a minority language spoken in the Friuli region of northeastern Italy, which is where Casarsa is located. He did not speak the language but learned it through writing poetry, saying he “learnt it as a sort of mystic act of love, a kind of félibrisme, like the Provençal poets.” In 1942, Pasolini published his first collection of poems in Friulan, Poesie a Casarsa. He changed his opinion about Fascism in this period as well, gradually shifting to Communism. To wait out the Second World War, Pasolini’s family took shelter in Casarsa, where he joined up with other enthusiasts of the Friulan language and worked together on a magazine. He also taught students unable to reach their schools and had his first experience of attraction to another man with one of his students. Pasolini tried to distance himself from the events of the war, but was devastated when his brother Guido died in an ambush planned by the Italian Garibaldine partisans and the Yugoslav guerrillas in 1945.

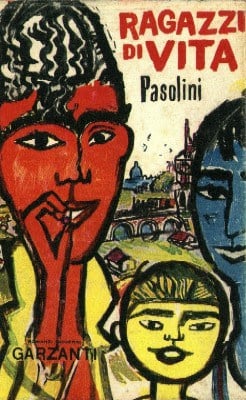

After the war, he continued to publish collections of poetry, and in 1950 he and his mother moved to Rome to start a new life. Here, he found inspiration in the rough Roman suburbs, and he wrote his first novel Ragazzi di vita in 1955, a story about the street urchin Riccetto. He continued to write novels and poetry, and started working on several of Federico Fellini’s films, writing dialogue for some scenes. He made his debut as an actor in Il gobbo in 1960 and co-wrote Florestano Vancini’s La lunga notte del ’43 that same year. In 1961, Pasolini, nearly forty years old, started his directing career with the film Accatone (1961).

Pasolini’s Cinema

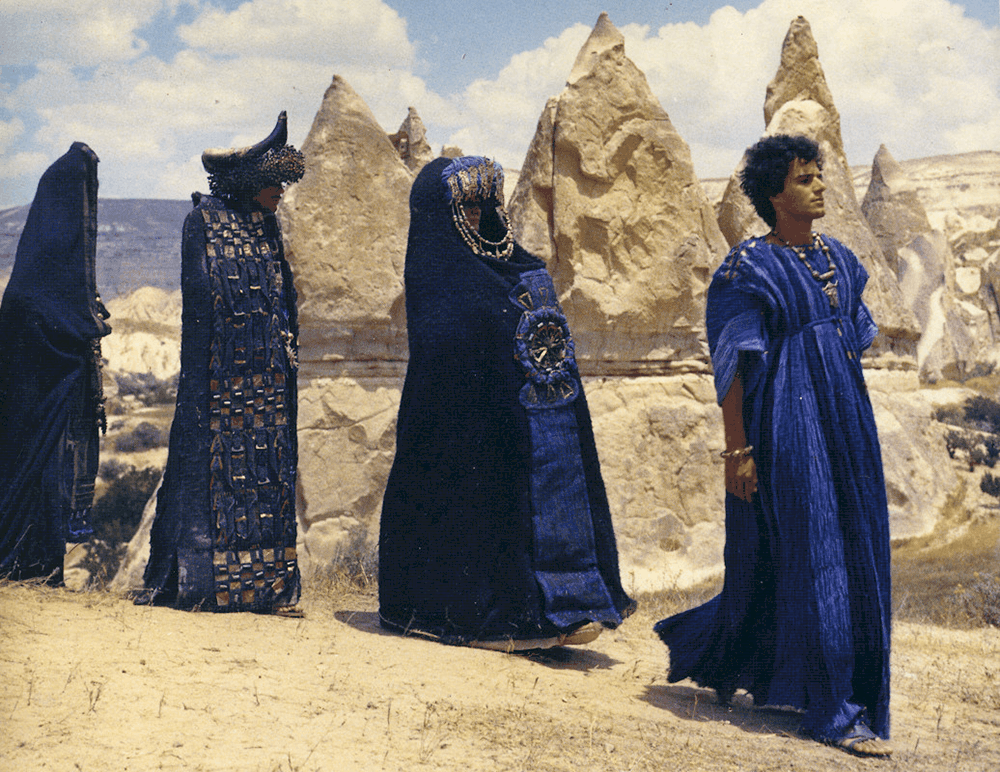

Accatone (1961) is a neorealist tale moving from gritty Roman housing projects to dreamscapes, telling the stories of pimps, prostitutes, and thieves. The movie polarised viewers, with some critics at the time calling it blasphemous. He tackled the great Greek tragedies Oedipus Rex (in the 1967 Edipo Re) and Medea (in his 1969 film starring Maria Callas). Between 1971 and 1974, Pasolini embarked on an epic trilogy, often referred to as The Trilogy of Life. The movies were based on literary classics: Boccaccio’s Decameron (1971), Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1972) and Arabian Nights (Il fiore delle mille e una notte from 1974). These movies are both playful and poetically sensual, filled with visually compelling shots – a testament to Pasolini’s understanding of the visual field, which he also grasped in his painting. Pasolini’s final work, Salò: 120 Days of Sodom (1975), was released two months after he was brutally murdered on the beach at Ostia. It was loosely based on the novel 120 Days of Sodom by Marquis de Sade, and is still considered one of the most disturbing films ever made, filled with intensely sadistic violence in many explicit scenes.

“What I have in my head as a vision, as a visual field, are the frescoes of Masaccio, of Giotto — who are the painters I love the most, along with certain Mannerists (for instance Pontormo). And I’m unable to conceive images, landscapes, compositions of figures outside of this initial fourteenth-century pictorial passion of mine, in which man stands at the center of every perspective.”

Pier Paolo Pasolini

The Visual Art of Pasolini

In Pasolini: A Biography (Random House, 1982), Enzo Siciliano includes a quote from Pasolini about his frontal approach to cinematography, which reveals Pasolini’s real feeling for the visual arts and the influence of great Italian fresco painters on his work:

“What I have in my head as a vision, as a visual field,” he states, “are the frescoes of Masaccio, of Giotto — who are the painters I love the most, along with certain Mannerists (for instance Pontormo). And I’m unable to conceive images, landscapes, compositions of figures outside of this initial fourteenth-century pictorial passion of mine, in which man stands at the center of every perspective.”

It is obvious then that for Pasolini, all these artistic fields intersected and just as painting entered his films, the cinematic entered his paintings and drawings. He started painting and drawing fairly early on, as a teenager, which offered him an emotional outlet. Two paintings from 1947 offer impressive visions of Pasolini’s creative spirit. One is his Self-Portrait with a Flower in His Mouth, another Man Washing, showing a male nude from the back washing himself. Both paintings are deeply sensual, hinting at the desires that lived in Pasolini. The self-portrait in particular captures the dramatic, visionary, and lustful darkness of the great director.

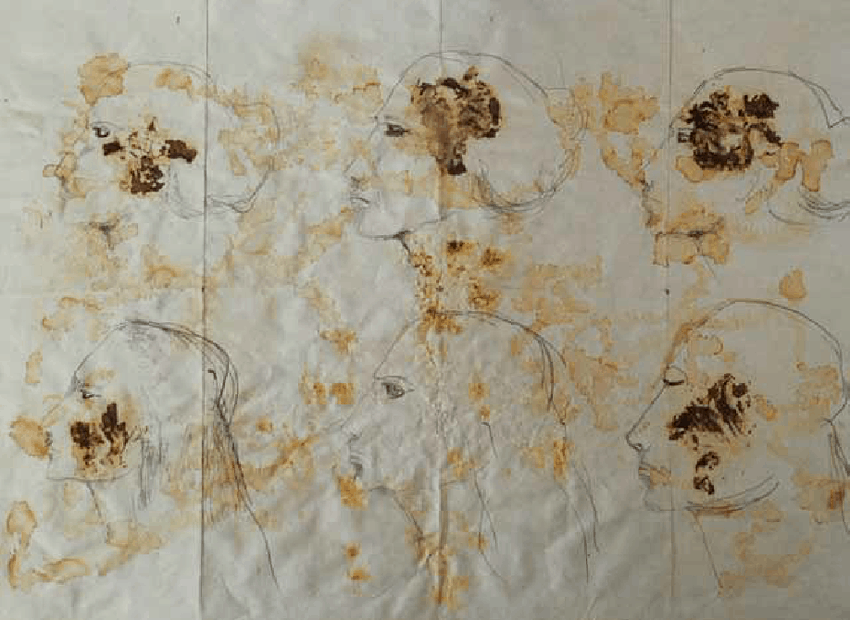

In the mid-‘60s and ‘70s, when Pasolini’s movie career was on the rise, he made several portraits of people he worked with who were important to him. Among them are Maria Callas (a portrait made with glue and sand and stained with the line of her profile repeated on several sections of a large, folded sheet of paper); and Roberto Longhi, whom he sketched in three caricatures in 1974 and 1975. He also painted Ninetto Davoli, Pasolini’s young, virulent love, whom he cast in several of his films. Pasolini experimented freely with techniques, sometimes using wine, coffee, and tea as paint, which resulted in almost sculptural, deeply alive paintings. Pasolini may have described himself as a dilettante when it came to the visual arts, in fact, had a bold and original understanding of the act of painting and drawing. He always did go against the grain, against the establishment, and against tradition, until the day he died. As he once said: “There must be some good reason why the idea never came into my head to attend some art lyceum or academy. The mere thought of doing anything traditional makes me nauseous. I mean literally sick to my stomach.”

Relevant sources to learn more

In 2012, Location One exhibited 40 drawings and paintings by Pasolini.

For previous editions of this article series covering famous directors who also made visual art, have a look at:

The Other Federico Fellini

The Other David Lynch

The Other Jim Jarmusch

The Other John Waters

The Other Alejandro Jodorowsky

Wondering where to start?