Exhibitions

Top Paintings, Drawings, and Cut-Outs From Henri Matisse – The Colour of Ideas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

By Shira Wolfe

“The selection of works demonstrate how the colour of ideas – a phrase attributed to Matisse by Louis Aragon – took shape in the course of Matisse’s almost sixty-year-long oeuvre through continually renewing colour chords and linear rhythms.”

Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

A recent exhibition titled Henri Matisse – The Colour of Ideas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, realized in conjunction with the Centre Pompidou presented a chronological overview of Henri Matisse’s oeuvre – the first one in the artist’s exhibition history in Hungary – while offering insight into the different genres in his work and the issues that were central to his art. Included in the excellent exhibition, besides his famous paintings, were drawings, sculptures, collages, artist’s books, cover designs, and the monumental designs Matisse made for the stained glass windows of the Dominican Chapel of the Rosary in Vence.

“The colour of ideas” is a phrase attributed to Matisse by the French Surrealist poet Louis Aragon, and the wide-ranging and versatile collection of works in the exhibition explored how this phrase connects to Matisse’s art as he constantly focused on the relationship between colors, lines and subject matter.

Famous Matisse Paintings & Drawings: Highlights of the Budapest Museum of Fine Arts

What follows is a selection of highlights from the exhibition: famous and lesser-known paintings, drawings and collages that show Matisse at his most innovative and creative.

Algerian Woman, 1909

Already at the beginning of his art journey, Matisse sensed his style was entirely unique. While studying art at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he frequently visited the Louvre to study the Old Masters and search for his own form of expression. Following a series of visits to Paul Signac in Saint-Tropez and to André Derain in Collioure in 1904-05, Matisse fully devoted himself to paintings of pure color.

At the start of 1909, Matisse visited the collections of East Asian Art of the Museum für Völkerkunde and the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin and set to work on a series of portraits of women in exotic costumes. Algerian Woman is one of these paintings. Here, Matisse combines sensual impact with decorative strength in the green fabric the woman wears, her pink cheeks, and the motif connecting the woman with the background. The execution of her face is already exemplary of Matisse’s later faces, stripped down and simplified by focusing on the curve of the eyebrows and the large almond-shaped eyes.

French Window at Collioure, 1914

During World War I, Matisse produced paintings with a more reduced language of form that hinted at abstraction. The anguish of those war years is more palpable in paintings from this period, with a darker and more somber atmosphere. In this period, Matisse also started more avant-garde experiments, following visits to the studios of artists like Pablo Picasso, Juan Gris, Gino Severini, and members of the Section d’Or group.

French Window at Collioure was painted while Matisse was living in Collioure, and most likely left unfinished when Matisse returned to Paris in October 1914. The window is a metaphor for vision in the Western tradition and World War I. According to Louis Aragon, this painting was “the most mysterious picture ever painted”. While the painting remained unknown to the public until the 1960s, it would continue to fascinate an entire generation of artists. It is one of the most surprising paintings by Matisse, and although he never truly recognized it as such, it can be said to be the closest to abstraction in his oeuvre.

Oil on canvas, 116.5 × 89 cm. Acceptance in lieu, 1983

© Succession H. Matisse. Photo credits : © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP

White and Pink Head, 1914

In this portrait of his oldest daughter Marguerite, White and Pink Head, Matisse went in an exciting new direction by exploring Cubism. He painted it after returning from Collioure, and the approach to this painting was triggered by conversations he’d had with Juan Gris about the Cubist works of Picasso and Braque. The portrait is composed of flat and simplified forms that create a geometric version of his daughter. At the time, the portrait was met with mixed responses, but there is no doubt that it is one of his greatest portraits that shows a powerful and original approach to Cubism. The strength lies in the fact that he was not trying to copy Braque or Picasso, but that he kept his own recognizable style underneath the Cubist approach.

Oil on canvas, 75 × 47 cm. Purchased, 1976

© Succession H. Matisse. Photo credits : © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP

Interior, Goldfish Bowl, 1914

Matisse moved into an apartment on 19 Quai Saint-Michel in Paris in 1913. Here, he painted Interior, Goldfish Bowl, one of his most complex paintings addressing the study of space. The goldfish bowl at the center of the composition creates an ambiguity in the space: it is both part of the surroundings while also a separate world of its own. Included in Matisse’s series of paintings exploring the complexity of space, in Interior, Goldfish Bowl he worked with the motif of the window, his studio, and the view of the Seine. The color blue connects all the different elements in the painting, while the different shades of it, lighter and darker, create perspective.

“I have never been so clearly advanced in the expression of colours.”

Henri Matisse

Seated Pink Nude, 1935-36

In 1930, Matisse traveled to Tahiti and the United States. These travels brought about a new shift in his paintings. The nudes he painted in this period were monumental and reduced to almost geometric forms. He was focused on reinterpreting the relationship between the figure and the background plane. In this period, he also photographed the different stages in his works, and then kept reworking the paintings and simplifying them, often by wiping or scraping off paint. It is with this approach that Matisse worked on Seated Pink Nude, a painting of his favorite model Lydia Delectorskaya. The painting had 13 different stages, and the canvas shows the traces of Matisse’s reworking and simplification. The final result is a powerful and mysterious figure with no face, just a ghostly blurring and a mirage of the different poses that she had taken in the previous stages. The separate phases of the process have become part of the final painting.

Oil on canvas, 92 × 73 cm. Acceptance in lieu, 2001

© Succession H. Matisse. Photo credits : © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI /Dist. RMN-GP

Face of a Woman (Starry Veil), L5, 1942

During World War II, in 1941, Matisse was diagnosed with duodenal cancer. Following a successful surgery, he found himself bedridden for nearly three months. During this time, he made a large number of drawings and illustrations, and developed a totally new art form since the productions of paintings and sculptures had become physically taxing for him – his cut-out paper collages or découpages.

In 1943, he published an album called Drawings. Themes and Variations, in which he laid bare his creative method: he would observe his motif and create a series of variations on it, with only slight differences, to get to the core of it and present it in the most concentrated form. The most often recurring motifs were female nudes and still lifes, and Face of a Woman (Starry Veil) is among one of his drawing series. His drawings also served as preparations for his paintings.

Pale Blue Windows (for the Chapel of the Rosary, Vence), 1948-51

Matisse moved from Nice to the small town of Vence in 1943, when Nice came under threat from bombardment during WWII. In Vence, he made his final series of paintings and more advanced expression of colors, known as the “Vence interiors”. The series is a summary of Matisse’s painting oeuvre. After that, he almost exclusively continued creating his cut-outs, or découpages, using paper and gouache – a method he had started working with after his surgery and weakening health. In this new context, Matisse continued to explore the harmony between color and line.

From 1948, the artist dedicated himself to the decoration of Vence’s Dominican Chapel of the Rosary. He worked with large cut-outs to create the patterned designs for the stained glass windows on the chapel’s southern wall. The second version of the designs Matisse made for the chapel is one of the centerpieces of the exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, titled Pale Blue Windows. The brightly colored motifs are memories of Matisse’s trips to Tahiti and Polynesia in 1930. Matisse did not only create the stained glass windows for the chapel but also painted designs of figures (saints and Mary holding the baby Jesus) on white tiles on the walls of the chapel, creating a fully immersive art piece in the chapel. The project was concluded in 1952, a couple of years before Matisse’s death.

Gift of Mme Jean Matisse and Gérard Matisse, 1982. © Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris and Szépmüvészeti Múzeum. Photograph by Shira Wolfe.

Designs for Verve, 1937-1949

In his cut-out work, Matisse first painted sheets of paper with gouache, and then cut out various shapes and arranged them into new compositions. Through this approach, he finally felt he managed to harmonize line and color, something he had been trying to achieve throughout his entire career.

In 1937, Matisse produced his first cover design for the art and literary magazine Verve, a publication by Tériade. He would continue to design covers for five other issues. Verve printed reproductions of works by artists including Matisse, Picasso, Braque, and Chagall. For the covers, Matisse worked solely with his paper cut-outs. In order to ensure that the colors were as accurate as possible, he designed the covers in the Tériade office, using color samples of the ink pigments for his cut-outs. The result is a beautiful collection of cover designs that create a visual harmony between text, image, color, and line.

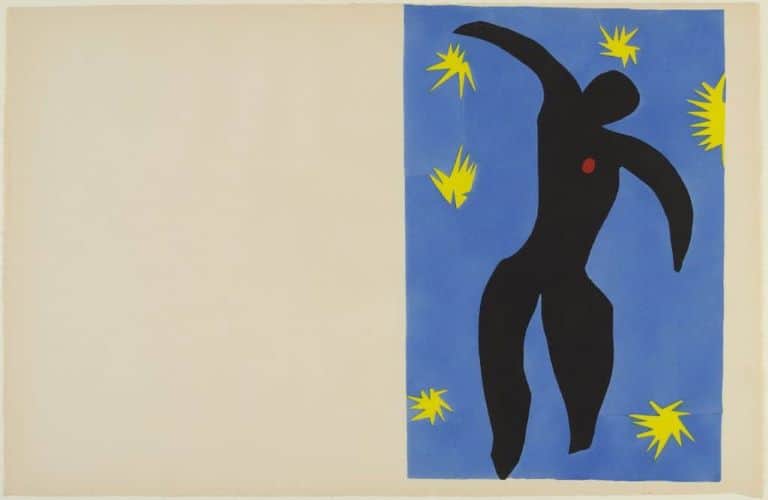

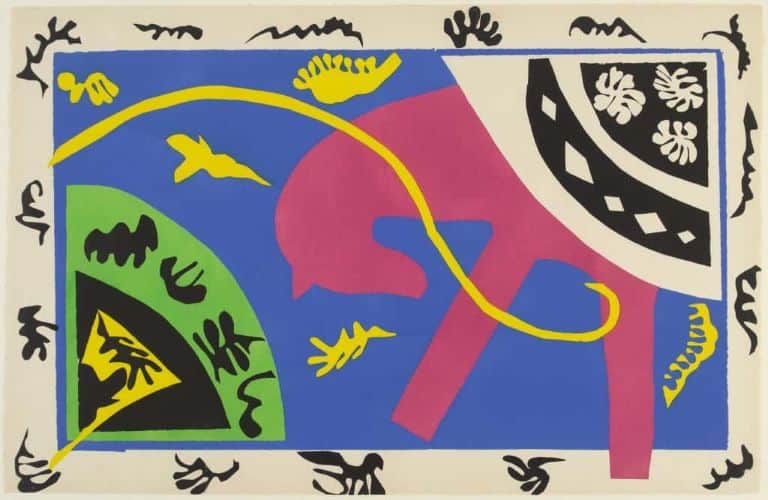

Jazz, 1947

In 1943, Matisse was commissioned by Tériade to create a series of stencils in gouache for a “book on color”, inspired by the work he had done for the Verve publications. The idea was to try out a technique that would enable the works to be easily reproduced. Matisse found a parallel in jazz music, saying: “Each red remains red, each blue remains blue – like jazz, in which each performer playing as a soloist increases his part of his fantasy, of his sensitivity.”

The technique of making color cut-outs subsequently became a practice in its own right – it was revealed to the public with the publication of the aptly named album Jazz. In the 1947 edition, Matisse chose to alternate color plates and manuscript pages with text written in his own handwriting, like a modern version of a medieval illuminated manuscript. Alongside his most famous paintings, Jazz is without a doubt one of the peaks of Matisse’s oeuvre, in which he found the perfect harmony between the lightness of his vibrant colors, the directness of his cut-out figures and motifs, and the simplicity of pared-down forms.

Paris, 1947. Portfolio of 20 plates. Pochoir on velin paper. Printed by Edmond Vairel. Inv. no. 67/100.

Anonymous gift, 1964. © Centre Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, Paris

Relevant sources to learn more

Keep reading on Artland Magazine

Trace Matisse’s artistic development in our article about his art, life and legacy

Read our article about the history of collage in art

Other relevant sources

Read more about the exhibition Henri Matisse – The Colour of Ideas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest

Discover available works for sale by Henri Matisse on Artland

Wondering where to start?