Articles and Features

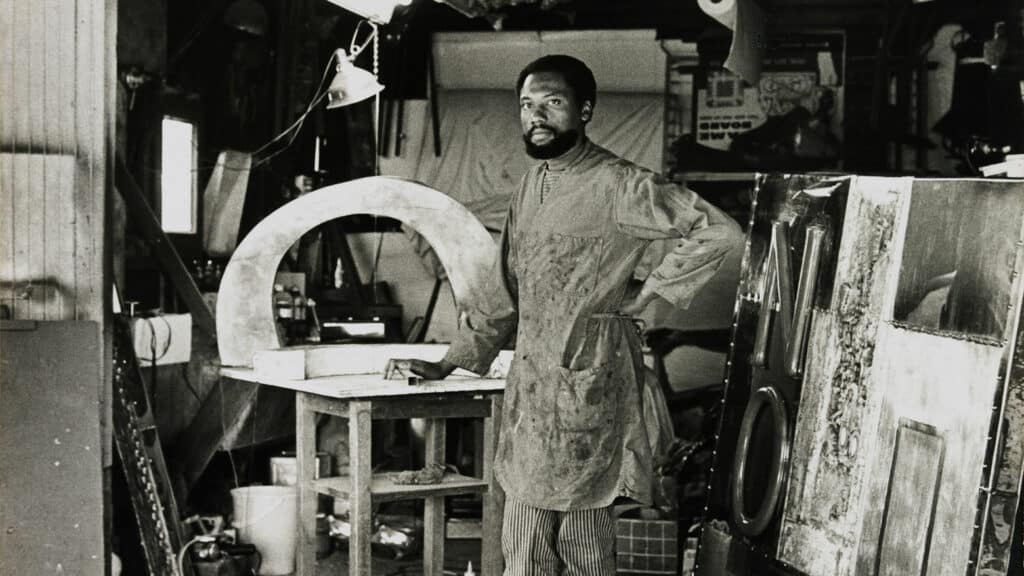

A Tribute to Pioneering Assemblage Artist John Outterbridge

By Shira Wolfe

“Art and the creative process always belonged to humanity at large. No matter what their complexion, no matter what their posture, people always expressed themselves in some way. That expression, to me, has always been about some form of art.”

John Outterbridge

John Outterbridge, a pioneering figure in the Los Angeles art scene since the 1960s, passed away on 23 December 2020 in Los Angeles at the age of 87.

For decades, he was the director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, known as an important centre for arts education and a conduit for social change. We take a look at the artistic practice and legacy of the artist and activist.

An upbringing that defined an artist

John Outterbridge was born during the Great Depression in 1933 in Greenville, North Carolina. Growing up in the American South during the Jim Crow era, Outterbridge experienced a culturally rich, but segregated upbringing. In a 2013 interview with Art in America, he talked about the immense presence of creativity and art in his community while growing up. It was an environment where everything was visualised and there was a strong tradition of folk art. He explained: “Picket fences were decorated with eggshells and, as a kid, you didn’t know why. It was some kind of ritual. For the culturally rich community that I grew up in, this was like language.” He went on to say: “Art and the creative process always belonged to humanity at large. No matter what their complexion, no matter what their posture, people always expressed themselves in some way. That expression, to me, has always been about some form of art. So I grew up not knowing I was doing anything but participating in life. I didn’t see art as a separate thing.”

Outterbridge’s father was a haulier and mover who salvaged junk and recycled used materials. Their backyard was filled with scrap metal, discarded furniture, and other used goods. This had a profound effect on Outterbridge, who developed a natural knack for using found objects in his art.

Art school and the move to Los Angeles

Outterbridge studied engineering at North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro in 1952, then enlisted in the army. During a tour of duty in Europe, he was able to visit many art museums and explore his surroundings through painting. He was discharged in 1956 and moved to Chicago to study commercial art and illustration at the American Academy of Art. In Chicago, Outterbridge soon became part of a dynamic group of Black artists – artists including Archibald Motley and Margaret Burroughs were inspiring figures for Outterbridge in developing his artistic and socially conscious language.

In 1963, Outterbridge moved to Los Angeles, where he found himself surrounded by artists experimenting with different materials. Informed by his upbringing in an environment filled with found and recycled objects, Outterbridge started to explore the use of found objects as a new medium. In effect, he and other artists were searching for a new visual language that did not depend solely on representation, and, through assemblage and abstraction, they could develop the themes and ideas that they were interested in, in a manner that allowed them freedom from pre-existing visual types and styles. The exploration of his heritage, his personal struggles and those of the people in his community started to intersect naturally with Outterbridge’s interest in community activism.

“Sometimes you ask yourself, ‘What is art? And what do I care what it is called and what it becomes?’ The only thing I know about it is that sometimes it has a tendency to shake me up and to shake what is around me up.”

John Outterbridge

John Outterbridge’s assemblages

By moving away from the flat canvas and working instead with deconstructing and repurposing found objects and recycled materials, Outterbridge worked on breaking down the barriers created by the use of traditional materials in the art world, and the exclusionary policies in society. Without the traditional canvas and frame, he wove together the personal and the public in three-dimensional creations, freeing himself both physically and psychologically. His hauntingly beautiful assemblages offer reflections on the past and meditations on the future.

John Outterbridge: early works

In 1965, the six-day-long Watts Rebellion – a confrontation between black residents, police, and National Guardsmen – took place, leaving the neighbourhood in ruins and exposing the deep-seated inequalities of blacks and whites living in the inner city. Outterbridge created significant work following this experience, as he combined personal memories and broader historical themes in metal scraps, rags, and other found materials. An example is his 1970 work Case in Point, a sculptural work assembled from leather and other materials, which resembles a bag of grenades. On the luggage tag, Outterbridge placed the phrase “Packages travel like people”, indicating how he was made to feel during a 1955 bus journey in Richmond, Virginia, when he was made to sit at the back of the bus despite being in full uniform. The artwork confronts the racism that so many black people faced at home, after serving their country abroad during the war.

Ethnic Heritage Group series

Between 1970 and 1982, Outterbridge created his Captive Images dolls, as part of his Ethnic Heritage Group series, which emerged from the artist’s desire to teach his daughter about slavery. The artist used materials including fabric, beads, wood and leather to create doll-like forms, imbued with many references to African folklore and tradition, community and family. Though the dolls recall imprisoned bodies, Outterbridge at the same time imbued them with poetic power and multiple layers of meaning, allowing his figures to access many different realities.

John Outterbridge’s commitment to education and activism

Throughout his life, Outterbridge showed a huge dedication to education and activism. He was the co-founder and artistic director of Communicative Arts Academy (1969-1972) and the director of the Watts Towers Art Center (1975-1992). In this capacity, Outterbridge was an important figure to help increase visibility for black artists at a time when galleries and museums were still largely excluding black artists from their spaces. Even though these positions meant he had less time for his own artistic production, Outterbridge showed incredible selflessness and dedication to supporting other artists.

The legacy of John Outterbridge

John Outterbridge, along with fellow LA assemblage artist Betye Saar, represented the United States in the 1994 São Paulo Biennial. Though a constant important presence in the LA art scene, it took until 2011 for Outterbridge to have his first solo show since the 1960s. The exhibition was held at LAXART, and for the occasion, he created a site-specific installation from rags found on the streets of Los Angeles. More recently, Outterbridge was included in Soul of A Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Outliers and American Vanguard Art, Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles, and was also featured in the central exhibition at the 2013 Venice Biennale. Another important show came in 2015 when the Hammer Museum organised a solo exhibition of Outterbridge’s work at Art + Practice in Los Angeles. The show travelled to the Aspen Art Museum in 2016.

Today, Outterbridge’s works are in the collections of important institutions including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. His soulful, complex and poetic assemblage works remain an inspiring force for the future generation of artists and continue to move people with their relevant messages.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn about the history of collage and assemblage art here.

Read about how Louise Nevelson created sculptures from found objects and scrap wood from the street.

Other relevant sources

Art in America

The Hammer Museum

National Gallery of Art

Tilton Gallery