Articles and Features

Agents of Change: Camera Obscura

By Shira Wolfe

In our article series “Agents of Change,” we explore developments and innovations, both technical and technological, that had a seismic impact on artistic production and consequently changed it in key ways, forever. We learn how artists and the tools at their disposal evolved over the years and gave rise to new forms of art and ways of making them. In this edition, we explore the immense effect the discovery and refinement of the Camera Obscura had on the production of art.

What is the Camera Obscura?

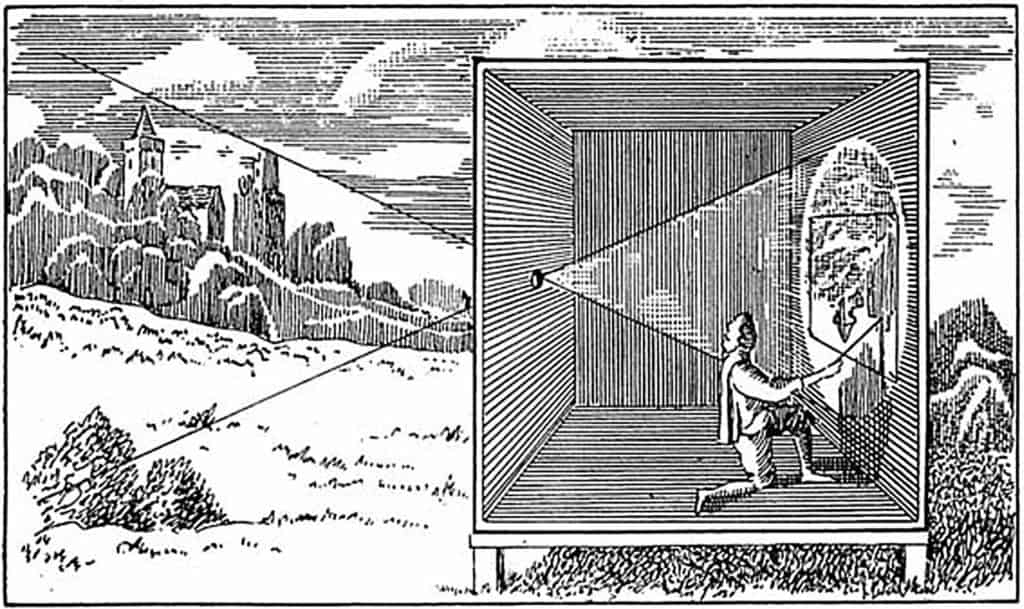

The Camera Obscura (Latin for “dark chamber”) is an optical device which is the ancestor of the photographic camera, but without the light-sensitive film or plate. It consists of a lens attached to an aperture on the side of a darkened tent or box. The light reflected on the chosen object outside the box passes through the lens and is projected onto the smaller-scale surface in the encased area. This projection, which appears upside down, can then be traced.

Early models of the Camera Obscura were quite large, consisting of an actual room or tent. Over time, more portable models were invented, leading to the wooden boxes with adjustable lens to provide focus. Eventually, a mirror was introduced to rotate the image which was projected onto a screen.

In the 17th century, artists started to make use of the Camera Obscura. They would use it to project images they wanted to paint, and subsequently trace them.

Who Discovered the Camera Obscura?

The Camera Obscura is an invention that is indebted to a great many thinkers and scientists from different parts of the world.

The earliest mention of the Camera Obscura dates back to Greek antiquity and the Chinese Han Dynasty (c. 468 – 391 BC). The Chinese philosopher Mozi was the first person to write down the principles of the Camera Obscura, while Aristotle wrote down his observations about the phenomenon in his book Problems, musing on the shape of an eclipsed sun projected onto the ground through the gaps between leaves of a tree.

The first person to suggest that a screen could be used to project the outside image onto was the 11th century scientist and philosopher Ibn al-Haytam (also known as Alhazen). The replacement of the pinhole with a converging lens was first described in the 16th century by the Venetian Daniel Barbaro. Leonardo da Vinci, who was familiar with the work of Alhazen, published the first clear description of the Camera Obscura in his Codex Atlanticus (1502). Finally, the actual term “Camera Obscura” was first used by the German astronomer Johannes Kepler in 1604. The German Johann Zahn, an expert on light, also wrote extensively about the Camera Obscura, and proposed a design for the first handheld reflex camera as early as 1685. It would take another 150 years for his design to be realised.

The Hockney-Falco Thesis

In 2001, British artist David Hockney published his book Secret Knowledge, which postulates that many of the great masters of the Renaissance, and even earlier artists, used optical devices such as the Camera Obscura for the creation of their art, essentially tracing the projected outlines of arranged tableaux as the basis for their sophisticated compositions. His theory created a great wave of controversy in the art world, since many people in the art establishment believe the use of a Camera Obscura undermined the received notions of talent and brilliance of these artists and how art historians had previously understood the complexity and precision of their works. Though it was known that some artists in the 18th and 19th centuries were using optical devices, this theory would argue that the first artists using these devices were doing so as far back as the 15th century.

During his research process, Hockney collaborated with physicist Charles M. Falco. Together, they came up with what is called the Hockney-Falco thesis, which goes as follows: “Our thesis is that certain elements in certain paintings made as early as c. 1430 were produced as a result of the artist using either concave mirrors or refractive lenses to project the images of objects illuminated by sunlight onto his board/canvas. The artist then traced some portions of the projected images, made sufficient marks to capture only the optical perspective of other portions, and altered or completely ignored yet other portions where the projections did not suit his artistic vision.”

Hockney and Falco suggest that the Belgian artist Jan van Eyck (1390-1441) and Italian artist Lorenzo Lotto (1480-1557) already made use of optical devices, such as concave mirrors, to help them create their realistic scenes. Jan van Eyck’s “Arnolfini Portrait” (1434) is one of their key examples. This painting reveals a three-dimensionality, individuality, and psychological depth which is lacking in earlier paintings, and Hockney and Falco are convinced this is in part due to Van Eyck’s use of optical devices.

Other Artists Associated With the Camera Obscura

Although it remains hard to provide actual proof that artists since the 15th century used the Camera Obscura to aid them in their detailed painting process, many scientists and researchers believe that the following 17th century artists used the invention:

Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675)

Johannes Vermeer was one of the great masters of the Dutch Golden Age in painting, and is known for his realistic, delicate domestic interior scenes of Dutch middle class life. The American graphic artist Joseph Pennell was the first person to suggest, in 1891, that Vermeer may have used the Camera Obscura. He pointed out the photographic perspective in Vermeer’s “Officer and Laughing Girl” (1655-1660). The figure of the officer, who is depicted sitting closer to the viewer, is much larger than that of the girl. The perspective is geometrically perfectly correct, which was quite unusual in most 17th century paintings. Another argument for Vermeer’s use of the Camera Obscura is his extremely faithful and detailed depiction of maps in the backgrounds of his paintings. It is therefore assumed that Vermeer used a simple booth-type Camera Obscura, with which he could project images onto the back wall of his room, which he would then trace.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

It has also been suggested that Rembrandt, arguably the most famous of the Dutch Golden Age painters, sometimes made use of optical devices and projections such as mirrors and the Camera Obscura. Researchers have suggested that the life-sized scale of portraits such as his 1660 “Self-Portrait” could be the result of the image being projected onto paper or canvas. Moreover, people have argued that Rembrandt’s extremely confident brushstrokes and the angles in his paintings point to optical aids.

Canaletto (1697-1768)

Canaletto was a Venetian artist known for his paintings of city views of Venice, Rome and London. He was also an important printmaker, who used the etching technique. Canaletto was long thought to have used the Camera Obscura in order to trace images of these city views, and create his extremely realistic portrayals of these cities. However, recent infrared photography of the artist’s pen-and-ink drawings, including his “The Central Stretch of the Grand Canal” (c. 1734), revealed extensive use of pencil underdrawing. This seems to point to the fact that Canaletto was not tracing the outlines of buildings in open air, following the use of a Camera Obscura, but rather that he was plotting out the scene with pencil and ruler in his studio.

From Camera Obscura to Modern-Day Camera

The Camera Obscura as a tool for artists from the 15th century onwards may remain a slightly controversial topic among art historians, scientists and researchers, but there is no doubt that artists have made use of the instrument throughout the centuries.

Over the years, the instrument developed into what we now know as the photographic camera. Where before, the images could be projected but not preserved, further developments finally made it possible to capture and preserve images. The French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce is widely accepted as the inventor of photography as we now know it. He produced the first partially successful photograph in 1816, on paper coated with silver chloride.

It is evident that the Camera Obscura was a true agent of change, changing the art world forever in the sense that it helped artists create more realistic renderings of life in their art, and that it led to the development of photography.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about the controversies surrounding the use of the Camera Obscura in art here:

Wyant College of Optical Sciences

For previous articles in this article series, see:

Agents of Change: Acrylic Paint

Agents of Change: How Printmaking Transformed Art