Articles & Features

Agents Of Change: The Internet.

Net Art and How The World Wide Web Has Created A New Medium

“When the machines are on and your fingers are on the keyboard, you are in connection with some space that is beyond the screen. And this space is only there when the machines are on. It’s a new world in which you enter. (…). It’s not about things, it’s about connections. Of course, we were prepared for this by conceptual art, by minimal art and all these movements. An electronic space is very easy to imagine once you have grasped the idea of conceptual space for an artwork”.

Robert Adrian

Try to close your eyes and think of a work of art. Not necessarily your favourite one or the most emblematic, just the first piece of art that comes to your mind. What can you picture? Most likely you are thinking of a painting or a sculpture. Depending on your personal preference, you may be visualising an artwork from ancient times, like a Renaissance gem, or a masterpiece of modern art. The more adventurous among us might be envisioning an installation or a performative action. But why not think of an algorithm, a software, or a code? In fact, these can be art too, as well as websites, bots, and images randomly found on the web – even though some might turn their nose up at this. These collectively are part of what has come to be known as ‘Internet Art’ or ‘Net Art’: a form of art specifically conceived through the internet, on the internet, and for the internet.

In the last decades, with its unlimited communication possibilities and access to data, the World Wide Web has completely shaken up our lives in every aspect, also resulting in a thoroughly new way of creating, sharing and enjoying art, making the web the most disruptive art medium since the mid-twentieth century.

“Art on the net is mostly nothing more than the documentation of art which is not created on the net, but rather outside it and, in terms of content, does not establish any relationship to the net. Net Art functions only on the net and picks out the net or the “net myth” as a theme”.

Vuk Ćosić

A short history of Net Art:

Net Art’s spectrum is so wide that it is difficult to define: it includes different manifestations ranging from scripts, and lines of code, to web browsers, algorithms, and search engines. However, to address the issue of definition, the German critic Tilman Baumgärtel identified six specific features that distinguish it: connectivity, global reach, multimediality, immateriality, interactivity, and equality.

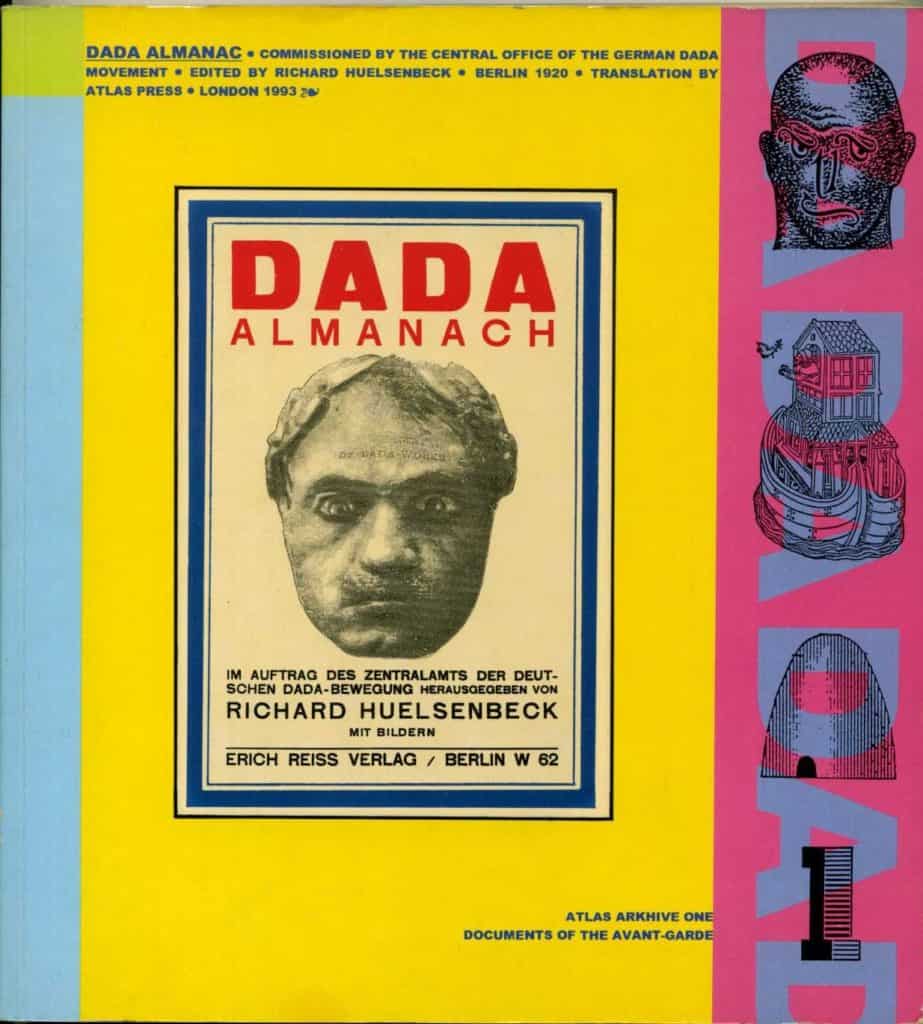

The beginning of the movement dates back to the nineties, with the early experiences often referred to as ‘net.art’ – with the distinctive dot in the middle. However, its roots can be traced back to the era before the web: in 1920, the Dada Almanach published by Richard Huelsenbeck provocatively proposed to create art via telephone; though far from imagining the power of the internet, the elements of communication networking, sharing and collective authorship were already present.

Similar aspects became part of artistic experiences in the sixties, in particular the so-called Mail Art movement which eventually merged into Fluxus.

With the purpose of bringing art out of the galleries, the pop artist Ray Johnson decided to use the postal service as an artistic element and began to send letters to friends featuring notes, doodles, drawings, and instructions to perform simple actions. Based on openness and inclusion, Johnson’s idea became a collective project that any person with access to a mailbox could join, resulting in a global movement that continues to the present day.

In the 1980s, when the internet was just for those in the know, the Canadian artist Robert Adrian began investigating the theme of an interconnected world via telecommunication networks. His seminal work The World in 24 Hours connected various artists in sixteen cities around the globe; each of them was given one hour – midday, local time – when to generate and transmit information over a wide range of devices and networks – computer terminals, telephone, fax, and TV – in order to guarantee the widest possible access through relatively affordable technologies.

With the advent of the World Wide Web, around a decade later, the legacy of these radically experimental experiences was continued by the Net Art. In the early years of the Internet era, many artists idealised the unlimited access to data and their widespread dissemination provided by the web, a utopia offering a democratic and participatory space where one could perform an innovative form of collaborative art that was also immaterial and not mediated by institutions.

For artists such as Vuk Ćosić, Alexei Shulgin, JODI, Olia Lialina, and 0100101110101101.org (today going by the moniker of Eva & Franco Mattes), the internet became a playground to elaborate connective and collective practices. They began to reflect on the relationship between virtual and physical space, addressing the themes of privacy, community, and the understanding of self with a subversive and intelligent approach to new technologies and the way these affect modern society.

Even though many net artworks are conceived using screens as postmodern canvases and therefore are bound to remain online, some others need a physical space to be best exposed and enjoyed; so it may happen to bump into a work of Net Art in more traditional spaces such as galleries and museums.

Net artworks over the years

Net Art’s nature is rather chameleonic: it does not have a strict aesthetic, evolving instead in a constant process that adapts its visual language to the rapid technological and social changes that facilitate it.

In many cases, it presents self-referential content, therefore the internet’s main features simultaneously become an artwork’s subject and its means of expression.

This is for example the case of the hyperlink. Artists have often used this key web characteristic as a storytelling tool to create a narrative.

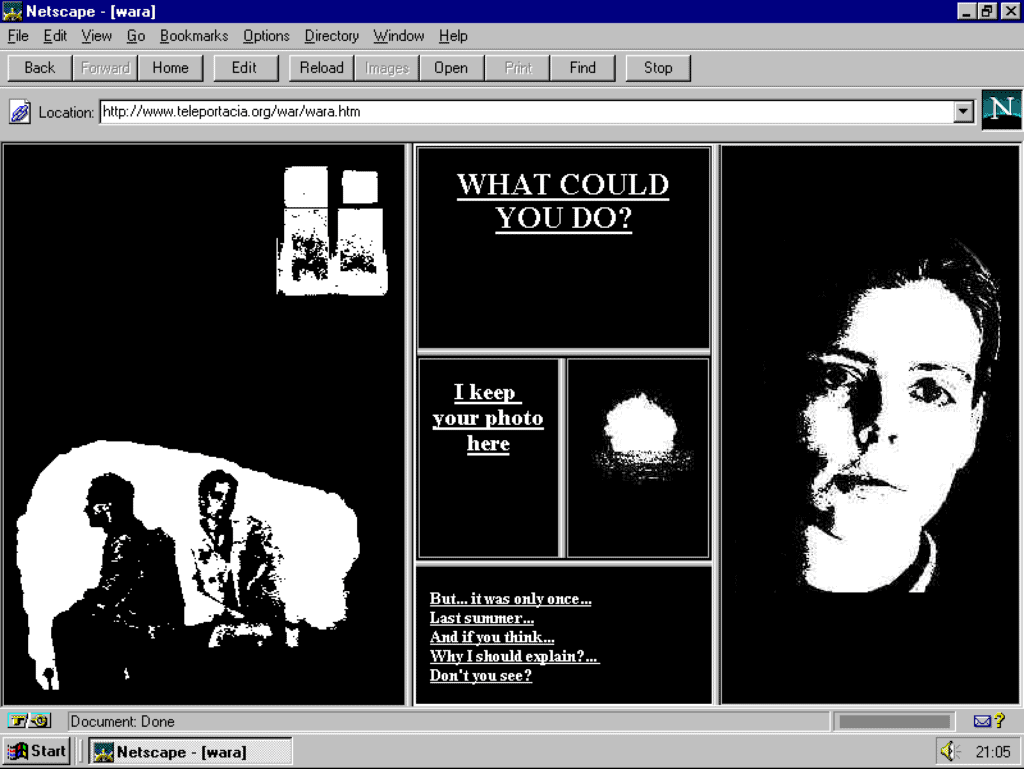

In 1996, when many people did not even know the internet existed and only ten million computers in the world had access to it, the artist Olia Lialina created the project My Boyfriend Came Back From the War, an early example of interactive hypertext storytelling that tells the story of a couple reuniting after a non-specified conflict. Today regarded as “one of the most influential net art pieces of the mid-nineties”, the work expects the user to unfold the dialogue between the two fictional characters by clicking on images and hypertexts in various sized windows within the frame – no matter the chosen path, the story never ends well. The work can still be enjoyed on the Net Art Anthology website and, if you happen to visit it, know that your internet connection is probably working properly and there is no need to check the router: the loading time has been intentionally slowed down to give an accurate impression of the slow dial-up speeds of the web 1.0.

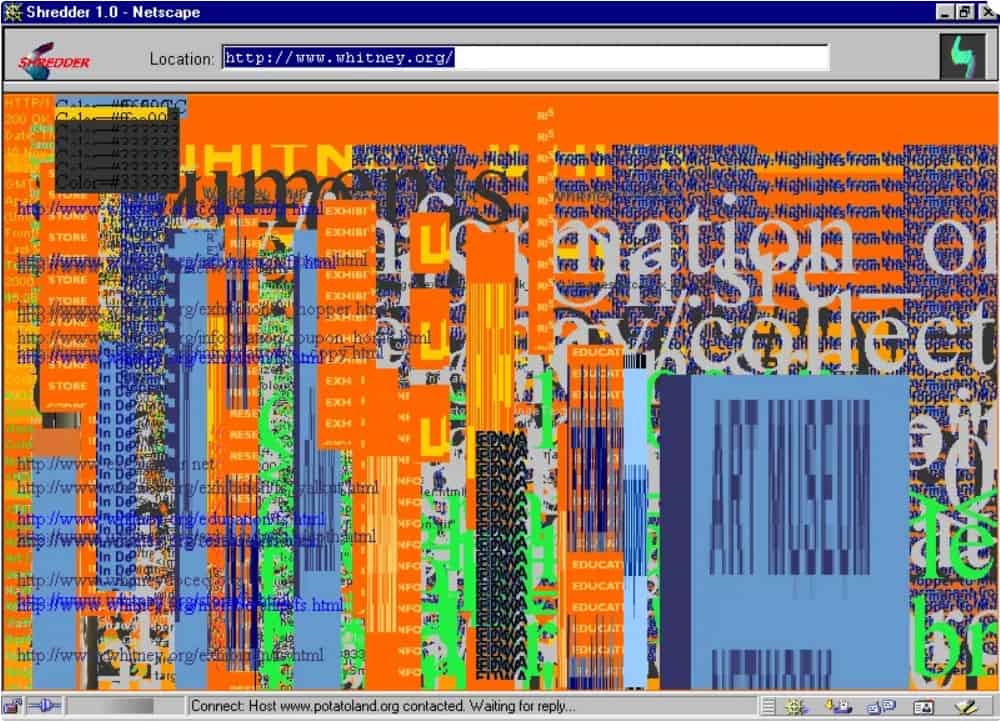

At times, Net Art aims to highlight the “materiality” and aesthetic aspects of the web’s constructive elements. With this purpose, in 1998, the artist Mark Napier programmed The Shredder, an unconventional browser that deconstructs web pages and displays them as if actually gone through a real shredder, “markup, text, code, images, and links are scattered across the screen like an instant Jackson Pollock. The raw material of the web revealed, torn and tossed onto a heap”.

With a similar artistic intent, the duo JODI launched a website to explore code aesthetics. Is it possible to find any beauty in rather chaotic and abstract layers of code? The artists’ answer is definitely positive; without any meaning hidden behind a rather straightforward formal research, they have created a boundless virtual maze for viewers to take countless paths and explore infinite navigation patterns.

However, not all Net Art is focused uniquely on itself. Many artists employ IT tools to convey strong messages of social or political nature and create critical debate around hot topic issues. This is the case of Darius Kazemi’s Last Words. A clear political statement against capital punishment, the project consists of a bot that accesses the Texas Department of Criminal Justice archive of all the last-word statements made by death row inmates, ultimately excerpting the sentences that include the word ‘love’.

Designing bots has become an increasingly common practice. In 2014, the London and Zurich-based art collective !Mediengruppe Bitnik programmed The Random Darknet Shopper, an online shopping bot with a budget of $100 in Bitcoins to randomly purchase items in the deep web on a weekly basis. The mysterious goods were shipped directly to an exhibition space – as a modern example of Mail Art – and, only there, unpacked and showcased. Among the unusual haul, the artists received a set of The Lord of the Rings, counterfeit clothing, a certain amount of ecstasy, and email addresses of millions of American citizens.

Just as artists, throughout history, have often found inspiration in the horrors of the mind – first and foremost Goya – the Swiss collective managed to display the “dark side” of society unveiling the secrets of the deep web market in broad daylight. The performance also raised some legal questions concerning the liability of a bot’s action. If a robot commits a crime, who is to be charged? A clear answer is still to be found; as for now, police have seized the ecstasy but did not charge the artists with drug possession.

A note on conservation

The nature of Net Art is process-based, interactive, and mostly ephemeral. From a conservation point of view, this opens broad new perspectives, and, simultaneously, causes new dilemmas. It challenges the concepts of both authorship and authenticity, actualising what Walter Benjamin had predicted decades before in his well-known The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. First of all, in the case of Net Art, authenticity usually lies in the lines of code, therefore it is the code that needs to be preserved, not the hardware: conservators have no interest in the tool used to run a software or to visit a website, but instead in the programming code behind that software and website. If you think of it, the same happens for literature: the value of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick resides in the language, the power of its words, and rhythm of its punctuation: one can read the novel in dozens of different book editions – or even on an e-reader – its significance and excellence will remain the same.

When considering technology, the other side of the coin is obsolescence.

Constantly accelerating technological development quickly renders many devices out-of-date that just a few years before were the most innovative. Today’s computers are already unable to perform many of the net artworks as they were originally conceived in the nineties. So, how to run obsolete software and documents on brand-new systems? A possible solution – though with some limitations – is given by the so-called ‘hardware emulation’: a strategy that consists in writing a piece of software mimicking the hardware behaviour of an obsolete computer. This way, a software belonging, for instance, to a 1995 net artwork, will run in a recent computer as if in one from 1995.

Many major institutions are now focusing on the documentation and preservation of Net Art – and ‘new media art’ in general; the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Institute of Network Cultures based in Amsterdam, among others.

New online platforms, like Net Art Anthology presented by Rhizome, are actively developing methodologies for archiving the internet, Net Art included.

They provide essential support for the development of tools and models to face the challenges posed by contemporary art with expanded theoretical foundations and practice – without overstepping conservation ethics. Operating in the intersection between conservation, archiving, and computer sciences, they also highlight the need to expand the skill sets of people involved in conservation – ranging from art historians to software engineers. Today more than ever, conservation is bound to become a cross-disciplinary field.

Relevant sources to learn more

Where to find net art:

Archive of Digital Art (Former Database of Virtual Art)

Rhizome’s ArtBase

Monoskop – Net Art

“Art in the Age of the Internet, 1989 to Today” – Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

For previous editions of the Agents Of Change Series, see:

Agents Of Change: Plastic. Or How Plastic Became An Era-Defining Material

Agents of Change: How Printmaking Transformed Art

Agents of Change: Silk Screen