Articles & Features

Art Beyond Boundaries. The Raw Appeal of Outsider Art

By Naomi Martin

“We are witness here to the completely pure artistic operation, raw, brute, and entirely reinvented in all of its phases solely by means of the artists’ own impulses.”

Jean Dubuffet

An Enigmatic Label

The phenomenon of Outsider Art has gained tremendous popularity in recent years, featured in international auctions, galleries, fairs, and engendering an ever-increasing number of specialist collections. Its appeal is universal, and so is the controversy surrounding its exact definition – is Outsider Art a synonym for self-taught art or folk art? Does it stand for naïve art of faux naïf? The perimeters of the genre are certainly intricate to define, but today, the phrase feels clichéd since it has almost become an umbrella term encompassing all forms of art made by folks outside of the more mainstream, contemporary art sphere. It even has its own hashtag, #outsiderart, with more than a million posts on Instagram, fueling a worn-out misapprehension of what it actually represents.

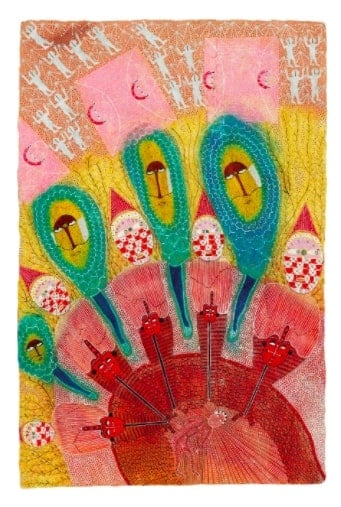

Authentic Outsider Artworks transcend genres. They are often peculiar and whimsical, and they defy our own perceptions of art, with a raw and almost alien quality which cannot solely be explained by an absence of conventional art-schooling. One detail not up for debate is the fact that Outsider Art emerged from psychiatrists’ researches on asylum inmates in the early 20th century, who discovered that creative expression could flourish beyond the pre-established conventions of art. In the 1920s, the world was thus introduced to a number of astonishing artworks, products of the uncanny and powerful products of a naïve creative strength, emerging from the channelling of a sincere and unbiased intuition.

Self-taught art is undeniably the category which overlaps the most with Outsider Art, as it alludes to artworks produced without prior artistic education or training, thus straying away from any particular style, or the standard definitions we have come to accept in the framing of fine art. But, unlike true Outsider Artists, the self-taught ones might just be enthusiastic amateurs, and may also have had more opportunities to visit museums, learn about art history and techniques via the internet or even by meeting with established artists. Outsider Artists on the other hand are creating without an audience in mind, and without any assumptions of style or aesthetic inclinations. Through their art they mirror their rawest and most powerful emotions, and often have no idea that their work could be seen by others – herein lies the most essential principle of the genre.

The term “Outsider Art” was first coined in 1972 by British writer and art historian Roger Cardinal, originally meant to stand as the English equivalent of “Art Brut”. But by the 1980s, the label had broadened, especially in the U.S., resulting in the ambiguity and sometime controversy surrounding the term today.

Art Brut

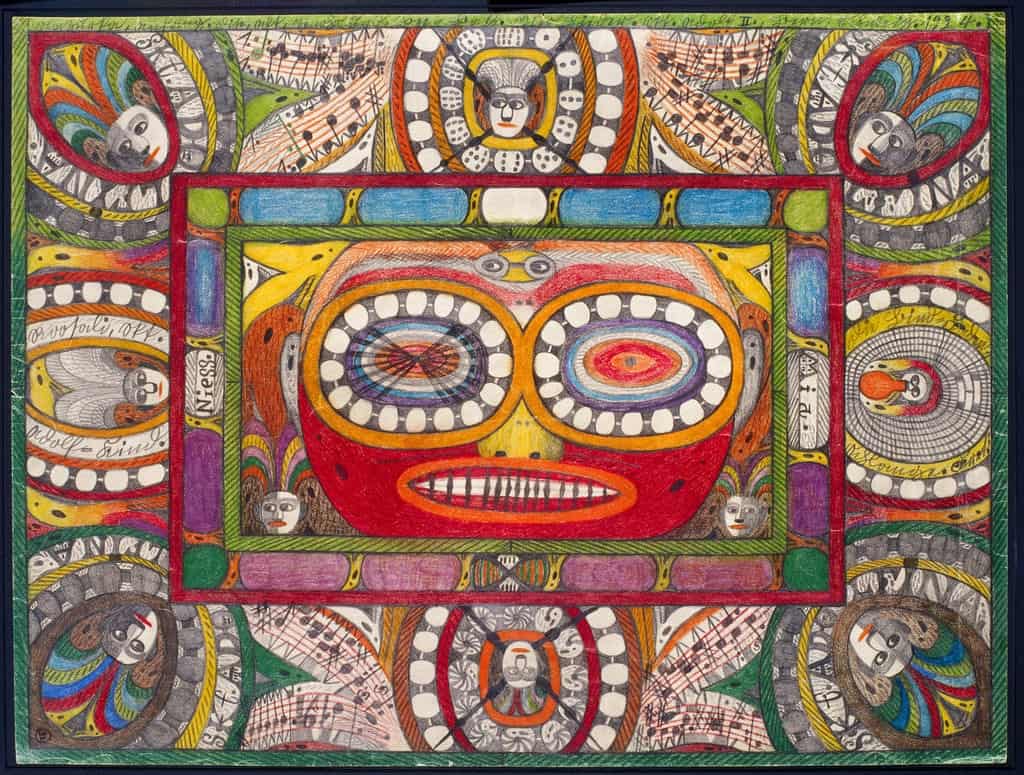

In the early 20th century, two doctors produced highly influential writings on art created by patients in psychiatric hospitals, originally intended for medical research. Swiss psychiatrist Walter Morgenthaler was enthralled by the artworks of one of his long-term patients, Adolf Wölfli, which he analysed in his book A Mental Patient as Artist (1921); while German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn documented and collected thousands of artworks by his patients in Artistry of the Mentally Ill (1922). The latter became a tremendous influence on the Surrealist movement and other artists of the time, in particular Jean Dubuffet.

Dubuffet was one of the most influential French artists of the post-World War II era. After studying Prinzhorn’s essays, he became utterly fascinated with the art of the mentally ill, which held, in his eyes, incomparable qualities and represented the purest form of artistic creation. Entirely immersed in the concept, Dubuffet found an inexhaustible source of inspiration for his own art, and founded the Compagnie de l’Art Brut in 1948, with one of Surrealism’s most acclaimed figure, André Breton.

With this organisation, Dubuffet sought to collect the works of these untrained artists, celebrating the raw quality untouched by academic rules and current trends with exhibitions and publications. He maintained that, because of its spontaneity and innocence, Art Brut was far superior to any other established genre marked by art-history.

Although it might have been considered as such, Art Brut was not solely the art of the psychologically troubled. Many works were indeed produced by asylum inmates, but Dubuffet explained in his manifesto that mental illness was not a criterion. Art Brut was instead meant to encompass the artistic creativity of minds sheltered from external influences, able to produce spontaneous and immediate artistic responses to their surroundings.

“By this [Art Brut] we mean pieces of work executed by people untouched by artistic culture, in which therefore mimicry, contrary to what happens in intellectuals, plays little or no part, so that their authors draw everything (subjects, choice of materials employed, means of transposition, rhythms, ways of writing, etc.) from their own depths and not from clichés of classical art or art that is fashionable.” (Jean Dubuffet, extract from: L’art brut préféré aux arts culturels)

Over the years following the foundation of the Compagnie de l’Art Brut, Dubuffet continuously looked for the “outsider” artists that would produce the raw artworks he marvelled at. His collection grew considerably, and was eventually exhibited in the Museum of Decorative Arts of Paris in 1967, with approximately 700 works by 75 different artists. Dubuffet then donated the entire Art Brut collection – around 5000 pieces – to the city of Lausanne, Switzerland, and in 1976 the Collection de l’Art Brut was permanently established.

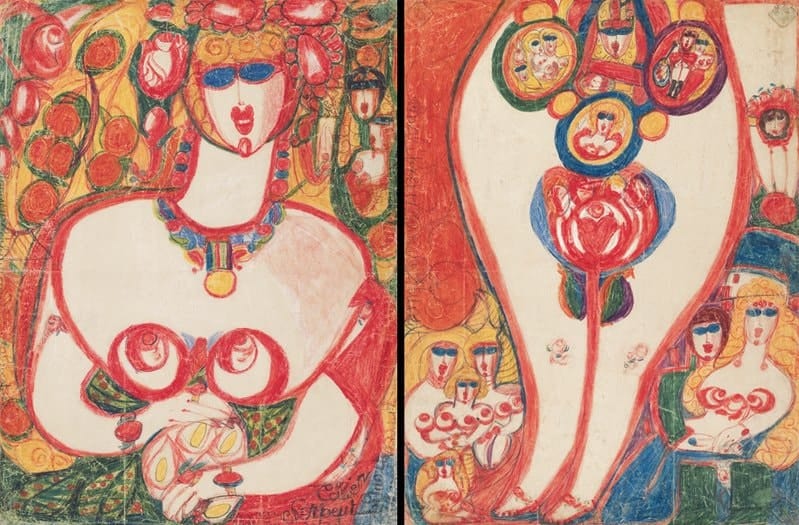

Roger Cardinal’s 1972 study of Art Brut which led him to coin the term “Outsider Art” was a significant milestone in the history of the genre, as it helped garner international attention and a new global following. A few years later, in 1979, Cardinal organised the exhibition Outsiders: An Art Without Precedence or Tradition at London’s Hayward Gallery, developing Dubuffet’s initial vision even further, by including the works of American artists such as Martin Ramirez and Henry Darger.

With this exhibition, Cardinal opened the door to more artists and thus challenged the stricter limits previously imposed by Dubuffet; Art Brut and Outsider Art merged into an international sensation, unifying a greater variety of artworks, but still retaining the same pioneering core and values. By the 1980s, the term “Outsider Art” stretched to include all kinds of works produced by marginalized artists, including those who had been previously labelled as Folk Artists.

Throughout the 1990s, the rise and recognition of Outsider Art became unquestioned. Mainstream museums and galleries started to pay attention to the genre, acknowledging its worth and accepting it as “serious” art. Most recently, a number of events solely dedicated to the works of Outsider Artists started to emerge, such as the eponymous Outsider Art Fairs of New York and Paris, and the representation of the genre in established exhibitions, most notably with the 55th Venice Biennale or the retrospective on Henry Darger at the Museum of Modern Art of Paris.

Today, despite its misleading label, Outsider Art is booming. Pieces that would have gone for a few hundred dollars in the 1970s are now reaching six figures – Christie’s 2019 sale of Outsider and Vernacular Art even brought in over $4m, consolidating the idea that Outsider Art has now been accepted and recognised by the art market, from collectors to mainstream museums.

Raw, “uncooked” by the art world, Outsider Art continues to amaze and surprise today, as its boundaries are becoming more and more fluid. Minorities, migrants, disabled, mentally ill, self-taught – all these “outsiders” are essentially united by a powerful personal desire to create primarily for themselves, depicting without formal training entire worlds of their own, in the purest and rawest form. Outsider Art is here to stay, now considered a fundamental branch of the art historical canon and every bit an established insider of the art world.