Articles and Features

Art Movement: Symbolism

By Shira Wolfe

The enemy of didacticism, declamation, false sensibility and objective description, symbolic poetry seeks to clothe the Idea with a sensory form (…) The essential character of symbolic art consists in its never leading to the concentration of the Idea in itself. Thus, in this art, scenes of nature, the actions of human beings, all concrete phenomena are not there to manifest themselves; they are sensory appearances intended to represent an esoteric affinity with primordial Ideas.” – Jean Moréas, Symbolist Manifesto

What is Symbolism?

Symbolism emerged in the second half of the 19th century, mainly in European countries where the population was largely Catholic and industrialisation had developed to a great degree. It was a period in which positivism promoted the arrival of a better world, based on reason and technology. Many people mourned the loss of the life they had known before, as countless people moved to the cities for work. The immense change brought about by the Industrial Revolution created this great clash between the traditional, symbolic world and the new reality with its different values. Especially in Catholic countries, notions of what had typically been considered good and evil were being questioned. As Walter Benjamin noted: “The devil appears where modernity comes into contact with Catholicism.” Starting as a literary movement, Symbolism was soon identified with the art of a young generation of painters who wanted art to reflect emotions and ideas rather than to represent the natural world in an object way. They were united by a shared pessimism and weariness of the decadence in modern society.

Key period: 1886-1918

Key regions: France, Germany, Austria, Scandinavia, Poland, Czech Republic, Belgium, Netherlands

Key words: symbols, melancholy, meaning, dreams, nature, subconscious, pessimism, idealised past, romance, allegory, sexual awakening, desire, mythology

Key artists: Arnold Böcklin, Gustave Moreau, Paul Gauguin, The Nabis, Odilon Redon, William Degouve de Nuncques, Fernand Khnopff, Jan Toorop, Gustav Klimt, Edvard Munch

Symbolism in France

Symbolism initially emerged as a literary movement in France in the 1880s, and became popular in 1886 following the publication of Jean Moréas’s manifesto in Le Figaro on 18 September 1886. Moréas, who was reacting against the rationalism and materialism pervading Western culture, believed in pure subjectivity and the expression of ideas rather than a realistic description of the natural world. However, Gustave Moreau can be said to be one of the very first Symbolist artists – he was already exploring Symbolist themes 20 years before Moréas’s manifesto, for example in his painting The Apparition (Salome) from 1874-76.

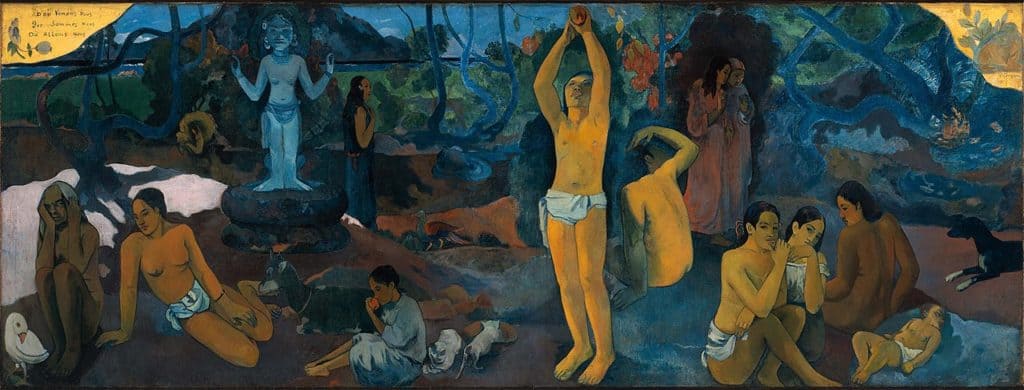

Albert Aurier published an article about Paul Gauguin in 1891, in which he gave the first definition of Symbolism in aesthetic terms. He described it as the subjective vision of the artist expressed through a non-naturalistic style, and named Gauguin its leading figure. Many of Gauguin’s artworks such as The Yellow Christ (1889) and Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? (1897-1898) are considered key Symbolist works. Gauguin sought to escape from the industrialized world by exploring what were considered primitive cultures. The art group Les Nabis, under the guidance of Gauguin, also made a large contribution to the transition to Symbolism.

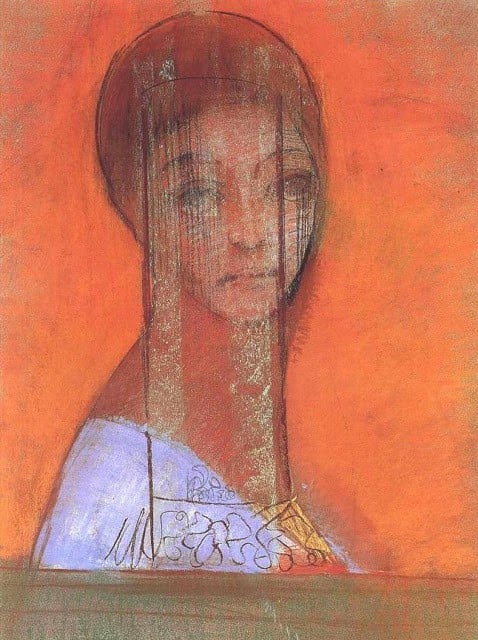

Meanwhile, Odilon Redon created his own version of Symbolism with a mysterious body of work with which he intended to bring people into the ambiguous world of the unknown, just as music does. Frequently taking inspiration from dreams and mythology, Redon explored the journey from darkness to light.

In 1892, the eccentric Sâr Péladan founded the Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, where he invited artists with strong Symbolist tendencies to exhibit their artworks. Several Belgian and Dutch Symbolist painters were among the selected artists.

Symbolism in Belgium and the Netherlands

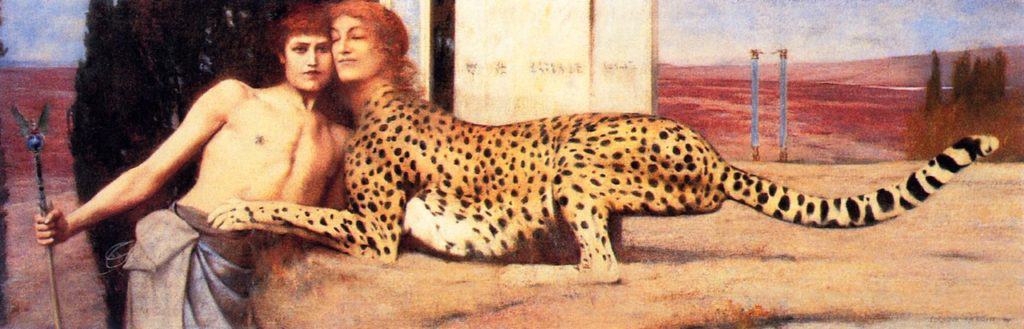

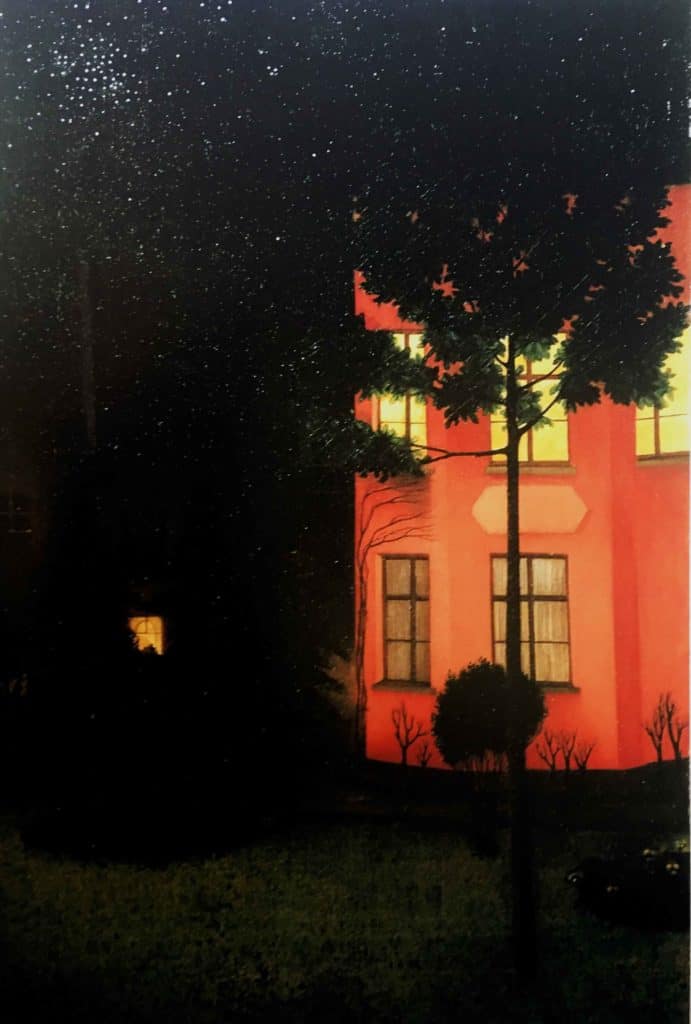

Fernand Khnopff was one of the Belgian artists showing at the Rose+Croix Salon, and his real breakthrough came when he exhibited at the Wiener Sezession. Khnopff’s Art (The Sphinx) is one of the most iconic Symbolist artworks. Also active in Belgium was James Ensor, who developed his own unique take on Symbolism based on carnivalesque figures. Perhaps one of the most unique Belgian Symbolists is William Degouve de Nuncques, whose intimate works delve into the secretive world of dreams and imagination. His paintings are almost always set in the dark night, illuminated by stars or lit-up windows, thus creating a deep meditation on our inner world.

Two of the most important Dutch Symbolists were Jan Toorop and Johan Thorn Prikker. Toorop came into contact with Symbolism in Belgium, and he in turn inspired Prikker to explore the movement. Toorop spent his childhood living on Java in Indonesia, which had a huge impact on his art and his exploration of the dream world, the subconscious and the shadow world. Shapes inspired by Javanese shadow puppetry can often be found in his work.

“I know my fate. One day my name will be associated with the memory of something tremendous — a crisis without equal on earth, the most profound collision of conscience, a decision that was conjured up against everything that had been believed, demanded, hallowed so far.” – Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo

The Germanic Countries

In the 19th century, Nietzsche and Wagner were two of the most important figures in the Germanic world. Nietzsche’s ideas and Wagners music set the tone for their generation and had a profound influence on the development of Symbolism in these parts. Nietzsche understood better than any philosopher of the time what the consequences would be of the demise of the old ideologies and values. He condemned the naivety of the learned men of his time who believed in their own superiority and was weary of the constant destruction of religious instincts.

In the Germanic countries, Arnold Böcklin, an artist born in Basel who spent a great deal of time in Italy, was an important figure in Symbolism. Böcklin’s approach to Symbolism was less gloomy than many of his peers. He was inspired by the warm light in Italy, and the aura antiquity. His most famous work is The Isle of the Dead (1880), of which he made five versions. He called the painting “a quiet place,” and he had made the painting for a young widow, who had asked him to make her an “image for dreaming.” In Austria, Gustav Klimt’s paintings reveal the close connection between Symbolism and parallel movements like Art Nouveau. Klimt’s lavish canvases explored the productive and destructive forces of female sexuality. Klimt’s work, which was often heavily criticised and even hidden from the public eye at the time, is a testament to the desires and fears of this period.

Symbolism in Scandinavia

In Scandinavia, the Norwegian Edvard Munch was closely associated with the Symbolists. He had spent time in Paris and then settled in Germany in the 1890s. His style is often referred to as Symbolic Naturalism, since his subjects are based on the real anxieties of modernity rather than on mythological or exotic representations. Exploring the deepest parts of the human psyche and suffering, themes that Munch frequently covered in his paintings include illness, loneliness, despair and mental suffering. He created his most famous painting, The Scream (1893), after a intense experience he had walking at sunset, when he was suddenly overcome with the deepest sense of despair, sensing an infinite scream passing through nature. This painting captures all the feelings of psychological anguish and isolation that exemplify the turbulent changes at the turn of the century.

Developments in the Slavic Countries

Important Slavic Symbolists include František Kupka, who was born in the east of Bohemia, and the Czech Alphonse Mucha. Both artists spent time living and working in Paris, and worked in styles often closely related to Symbolism. Mucha became famous for his Art Nouveau posters, which he created from photographs of models. Where Kupka delved deep into the realm of the subconscious, the supernatural and the suffering of the times, Mucha’s work was a great deal lighter and lacks that intense anguish and suffering so emblematic of most Symbolist works.

The End of Symbolism

The idealism behind Symbolism is the very reason it was later renounced. The First World War caused terrible disillusionment and the naïve beauty of Symbolist art was rejected and criticised. Modernism took over as artists went in totally new directions to oppose the violence and destruction of the war and deal with its traumas – movements such as Dada and Surrealism emerged, each in their own ways owing elements to Symbolism, while exploring new avenues and seeking answers in irrational, raw and primitive art.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read about Jan Toorop and Odilon Redon at the Kröller-Müller Museum