Articles & Features

Artist Activist Yves B. Golden in Conversation with Art For Black Lives Co-Founder Rob Franklin

Yves B. Golden is a multidisciplinary artist, writer, DJ and organizer. Her work explores visibility, dignity and the sacred bond that exists between memory and physical objects. She recently co-founded (alongside Remy @Goodwitch.nyc) the Herbal Mutual Aid Network, a grassroots organization providing free plant-based care for black people seeking support amid the ongoing crisis of racist violence and inequity. Her collaborative and solo works have been exhibited at Serpentine Galleries, London; New Museum, New York; ICA London; NADA Miami; Yaby Madrid; Springsteen Gallery, Baltimore; Caleb Bingham Gallery, University of Missouri and Raw Material Company Senegal. She is the author of the books of poetry Yves, Ide, Solstice (East Village Publishing) and Good Fist of Creation (Enes Publishing), which recently entered its second print.

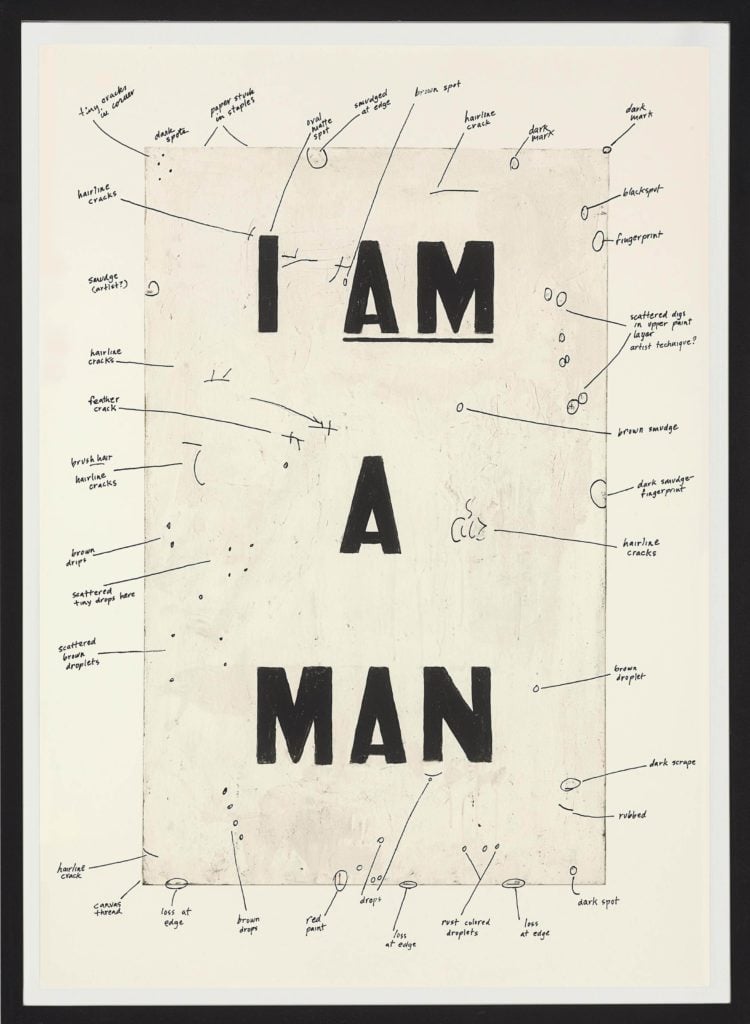

Yves is also a contributing artist to Art for Black Lives — a fundraising initiative, organized by myself and Berlin-based critic and curator Camila McHugh, which allows visual artists to donate prints for sale with all profits offering resource support to the Black Trans community. Golden’s contribution to our first round of fundraising, Erasure Report, draws inspiration from conceptual artist Glenn Ligon’s Condition Report (2000), an annotated reproduction of the protest placards held in the 1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike. Annotations on the physical wear of the placard over time invite questions around how the subject matter has been likewise warped due to prolonged exposure, implicating, in the artist’s words, “changing ideas about the relationship we have to the Civil Rights Movement.” In Golden’s version, the inquiry “What Happened” is ostensibly answered in gold text, tracing the names of victims to violence, while a “barely visible black text” itemizes critical context lost to the black background. She describes the work as an attempt to “further shift the conversation to Black (Trans) Women and our urgent need for care and protection.”

See all donated benefit works for R2 in Artland’s VRoom virtual exhibition here, and the full selection of works and availability at artforblacklives.org.

Over Zoom, from different parts of Southern California, Yves and I discussed rage, organizing and artmaking as they relate to the lived Black and Black Trans experience. Our interview has been edited for clarity.

Rob: There seems to be a great deal of conversation around “mutual aid” in our present moment. In May, Jia Tolentino published an essay in The New Yorker that traces the history of mutual aid from its anarcho-Communist roots in the early 20th century to the renewed interest amid COVID-19. To begin: what in your view distinguishes mutual aid from more traditional models and notions of charity?

Yves: When you sent me that New Yorker article, I kind of gagged because the way it was discussing mutual aid was definitely aware that this wasn’t a new thing, but was still like mutual aid has entered the mainstream, and I just have to assert that mutual aid has always been a part of my life and a part of my community in a broader sense. I remember all too well the “it takes a village” model within my Black, at times super militant, community in Rochester, NY and also in Trinidad — how everyone just takes care of each other, keeps an eye out.

I think the difference between charity and mutual aid for me is that charity comes from a place of excess. Socially, when charity work is being addressed, it’s coming from really rich or privileged people giving to poor people, whereas mutual aid is just about human compassion. And that’s the other thing about The New Yorker article: there’s this weird connotation that now, because of coronavirus, people are turning to mutual aid, when I’m like, people have always needed support. It’s never not been about supporting your community. I just think it’s worth mentioning that Black and Trans and Queer communities around the country and world have always been riding for each other and been very compassionate for one another. A global pandemic didn’t bring it into the mainstream.

Rob: Yeah, I agree. In the article, Tolentino mentions the “Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries open[ing] a shelter for homeless trans youth, in New York, and the Black Panther Party start[ing] a free-breakfast program,” but the bulk of the article certainly isn’t focused on mutual aid’s roots in Black and Queer communities. It reads like a trend piece.

But I wonder, what do you think is particular to those communities — the radical Black community in Rochester, or your community in Trinidad — which made them more likely to look out for one another and engage in mutual aid than say, America widely?

Yves: It’s such a complicated question because I don’t know what went wrong. I think it’s something to do with the pace of major cities and people just not having the capacity to look out for each other. Being in a city like New York, where I was living for nine years, there was definitely a moment when someone had to grab me and be like “this is your community now,” because nothing about the infrastructure is ushering you into that, especially as a Black Trans person. I literally needed someone to take me into the underground, to Spectrum, to then in the daylight have someone be like, “oh let me get you a ride home,” or “did you have something to eat tonight”, or “how are you doing on rent?” Whereas the difference in Rochester or Trinidad is it’s just not the same pace or self-preservation model. In New York people generally speaking are just like “I need to get rich or die trying,” or gain some fame or burnout, and it leaves you less capacity to tune in to the needs of a broader community.

R: Also, RIP Spectrum…

Y: I know, right? I just remember my first time going and people in the morning being like “Oh hey, I’ve never seen you around. Take my number so you can text me when you get home.” It took me entering into the dingiest club space ever to like, gain community, to gain some family.

R: So what’s the origin story behind the Herbal Mutual Aid Network?

Y: The short story is that on the 28th I landed [in Los Angeles] and all hell broke loose. Trump tweeted some fuck ass shit — when the looting starts, the shooting starts — and I had a meltdown. And the next morning I was like, I need something tangible to change. Or else, I don’t know how far I can make it into this episode, and I don’t know how long it’s gonna last. So I hit up some friends. First and foremost, I hit up all the girls that I know and was like what do you need, and the first thing that came up was something to calm me down. And then I hit up Cara, I hit up Remy. And this was even before I started reposting a lot of materials about how to stay engaged, what to do, etc. My first posts were really just like, what does my Black family need right now. And Remy hit me back up really serendipitously to say that she was planning to write me. And the rest is history.

We just rolled with it, reached out to so many people to get financial and material supplies. As co-founders, Remy and I, we have different perspectives on how to tap into what people need. Remy is an herbalist and a really good one. She knows what tinctures, topicals and herbs can help people in different situations. I’ve been organizing for a while, but nothing to this extent. Probably to my detriment, I’m a bit of an empath, and I feel a lot when things are not good. I can only imagine and briefly step into how other people around me are feeling, and all I can think is what can I give that will offer some relief, even if it’s just a gesture of “I’m here for you” or “I care for you.” I want that to be given before it needs to be asked for.

R: In my understanding of mutual aid, there’s an element of reciprocity and there’s also this element of cultural specificity — the idea that neighbors are best suited to help neighbors. I’m curious with your project, what is the type of care that you can provide for your community that people outside of the community are less able to? What is the import of that specificity?

Y: If I were to be kind of abstract, I think that the whole point for me is really thinking about the collective, and that feels really culturally-specific. What feels most connected to my ancestors and my community and upbringing is, not even creating new community, but tightening community up, and I do have this feeling that that’s so specific to my culture. The reason to care and to be there for each other has always been there. And that’s the thing that’s most infuriating about the notion that this could be a trend or even just perpetuating this notion that something like Wellness is trendy; it just means that you think there will be a new trend after it.

These times are, in a lot of ways, unprecedented, and there’s no real end in sight, so all that we can try to do is be present and mindful of what everybody is going through and what they need. It’s hard as fuck to do, and it takes a toll on you. I’m forgetting how I achieved a sort of restfulness before COVID. I was hustling and organizing, but I was still thinking about me and like, how I was going to get rent money, and taking jobs that I never wanted to take just so I could afford whatever, and now my whole day-to-day is so enthralled with other people.

R: I do think the counter-side to collective good is collective pain. I wonder if you’ve found the same?

Y: Absolutely. It has been a trial. I wouldn’t trade it in for normalcy, whatever the fuck that looks like, but I don’t want to be a martyr. I don’t like the idea of suffering for good. I think that goodness is supposed to just flow through people.

The civil rights movement wasn’t even that long ago, and we’ve witnessed the same issues, the same approaches, the same symptoms coming back. Or just resurfacing, and you’re just like damn, people died, went to jail, were beaten, bruised, and battered for us to still be here, like, asking for police reform? God help us… (Laughs)

I think what takes away from the good of seeing things change is that you also see a lot of people not putting in the work. It’s just a lot seeing the new world that you’re spending so much time working towards not being on everyone’s mind in the same way it is for you.

Like it feels so urgent for me: change. It’s always been urgent for me, on a personal level, to change and adapt and grow. And a lot of people really could not be bothered, and that’s going to be another part of how we look back on these times. Some people fought and died and were battered; some people lost sleep and peace of mind for equity, and a lot of their peers… And you know, now there’s an archive of you not participating.

R: I want to talk more about doing the work: what is the vision you see us working toward and what does doing the work toward that vision look like?

Y: Well, I think that part of the work is envisioning an equitable world. Like if you’re not thinking about what it could be, and you’re still stuck on what it was, then like, you’re not doing shit (Laughs). Just keeping it one hundred.

But if you’re white, or just not Black, you have to be willing to put your dreams, your visibility to the side for the moment, and it shouldn’t have to be begged of you. It should be a no-brainer, but it’s not a no-brainer for a lot of people. Folks have had generations to rise while other people were just trampled on. There’s been so little support unless there’s been a hyper visible violent scandal, so to speak. So, it’s like, don’t go on Instagram and repost a picture of Breonna Taylor with no personal anything — no instructions, no nothing — and follow that with a video of you doing yoga in the morning. Clear the channel. If you can’t or don’t know what to do then leave the space for the people who do. Give up your platforms. That’s the work.

Also donate. Reallocate resources. Have discussions with your family. Because all of this is just about resetting how we relate to one another. And it’s just too much to imagine that we’re not moving towards a better world, and this is what it takes. It takes empathy. It takes mindfulness. It takes sacrifice. It’s gonna cost though. It’s costing me. It’s gonna cost y’all.

R: Pivoting to your art practice a bit — having seen and heard your work, I’m really inspired by the balance of rage and dignity, or like demand for dignity, and I’m curious how you let the rage that comes from daily organizing and empathy inform your art practice.

Y: Wow (Laughs).

I am looking for a container to put the rage in. Or like a mechanism that uses the rage and creates something else. I’m thinking about an alchemical process to shift the rage into something productive. Into dignity, into grace. And a big part of my art practice is just working on myself, and creating the ancestor I want to be remembered as.

But with poetry and the rage, I don’t want to be a poet that screams. I grew up with performance poets, slam poets. My mom was a slam poetry coach, and I was always in the shadow of that because all those poets were like, oh well you’re a page poet, you’re never going to get up on stage and bleed. So I don’t want the poetry to scream. I do want to make that sort of soundscape with DJing though. I think that is the alchemy of turning the rage into productivity: you can put the rage into the atmosphere via sound and people move. People might even think a little.

R: I think often about that poem you read for Tabloid that includes the line “the rough, the battered, the brilliant, and truly beautiful people.” In the poem, that phrase “beautiful people” repeats like a mantra. How do you let mantras guide you?

Y: Part of the daily magic is having something to not only ground you but to propel you through to something. Mine right now is “all good things come to me,” and it’s just a way of reminding myself that no matter what is happening, the universe is conspiring for good. I think that’s part of envisioning an equitable world: just acknowledging that the universe wants the best for everybody, and believing that. It can be really difficult, straining, to believe that at times given how much information we’re getting to the contrary.

Speaking about the “beautiful people” poem: initially that poem was just about acknowledging that beautiful people suffer, and beautiful people sacrifice, and that’s not to say that that’s what makes them beautiful. Like I said earlier I don’t want to be a martyr; I don’t want to be pained for good. But I acknowledge that it’s a process, and having that discussion with myself, and knowing when to take a pause and put things away, that’s a part of imagining equity.

(Laughs) I’ve been quoting Bjork so much without even noticing but like, it doesn’t have to be a strife. We don’t want it to kill you to achieve something good in this world or to make space for good. So sometimes you just have to put it all away for a second. And I think that in an equitable world there’s space for that, taking breaks.

So there’s a bunch of mantras that swell around, and they all kind of ebb between self-care, caring for other people, making a better world, and also fueling your missions. And I believe in words, and that might be my last thing to say is that I really do believe in words, so when I say Fuck the Police or Black Trans Lives Matter, I really, really mean them, and I expect that to be what everyone else means when they say it, when they write it, when they repost it.

Rob Franklin is a writer and co-founder of Art for Black Lives, a print sale offering resource support to the Black Trans community. His work considers race, privilege and the intimate violence often bred in relationships across identity lines. He currently lives in New York, where he’s pursuing an MFA in Fiction at NYU.