“There has never really been a plan B”

With roots in the quiet, peripheral landscape of Denmark and parents working as psychologists, Danish artist Asger Dybvad Larsen has found himself absorbed in a space of reflection from an early age. A space of looking inward and reflecting on the process of coming into being, which has also become a defining element in his art. In this interview, Asger Dybvad Larsen contemplates his own practice and how it leads him to challenge the way he works with colour, form, scale and not least the process itself – a constant inconstant in his art and in his life!

This story has been published as part of a collaboration between Collectors Agenda and Artland.

You grew up in a small town on the west coast of Denmark. How do you think your upbringing has influenced your choice to become an artist?

I believe that there has always been some sort of creativity present in my life. Both of my parents are psychologists but they also have a creative side. My father plays music and my mother works as a volunteer at the Museum of Religious Art in Lemvig and even took courses at Aarhus Art Academy in her young days during her studies. I guess art has always been an important part of our family. My mother once decided on a rule; we had to visit at least one museum and one church every day, when we were on vacation. This meant that my siblings and I were introduced to art from an early age, and I have clear memories from museum visits throughout my childhood.

Can you recall how the desire to create art for yourself matured on you?

One of the earliest memories I have, of me being creative, is of my brother and I, when we would draw together. I remember us watching Terminator, and we used that movie as inspiration for our drawings. It was my brother’s idea and I looked up to him, so whatever he wanted to do, was always undoubtedly cool. In addition, I grew up in Fjaltring – a city where there is not a lot going on – so I found entertainment and relaxation in drawing, when I got home from school. I have always enjoyed being alone, and art provided me with a place where my thoughts could play freely. I remember an interview with Danish artist Claus Carstensen, wherein he talks about the cliché of the artist who is born with a need to create. Perhaps it was not a need for me, but I did naturally start walking the path of the art world. I have always received tremendous support from my parents, and I have never doubted that walking this path was the right thing to do.

Your work draws inspiration from influential figures in art history, sometimes by use of direct references to specific artists and genres such as post-war minimalism and conceptual art. Can you elaborate a bit on the interplay between your artistic practice and the roots of art history?

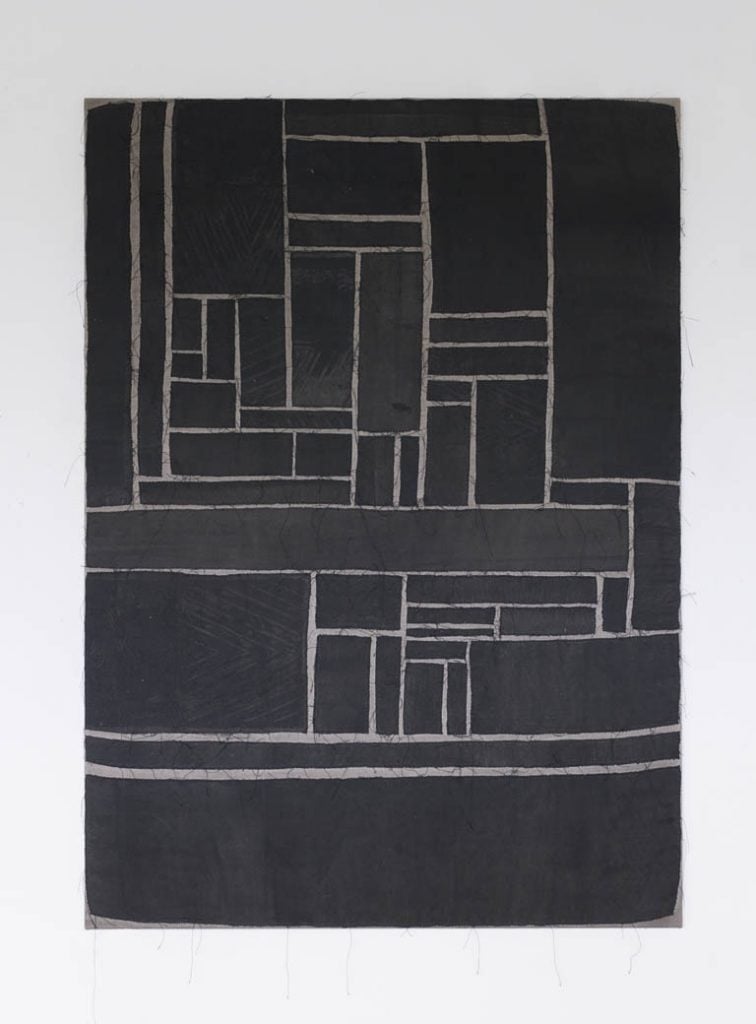

There are several ways to look at this – first, with my work as a starting point, and then a movement back in art history, or with my interest for art history as a starting point, with a movement forward to my work. There is an interplay where past and present are woven into each other, literally and metaphorically. To me, art is about combining things that I find exciting, with a respect for what predates my practice, and which has helped me develop the way that I am currently working. Inspiration, to me, moves on several levels – on one level, you have the artists that I actively reference, such as Frank Stella, Agnes Martin and Ad Reinhardt; on another level, you have the artists who I have a visual familiarity with, such as Piero Manzoni, Conrad Marca-Relli, Alberto Burri, Eva Hesse, Steven Parrino, Samuel Levi Jones and Sterling Ruby, and on a third level you have the artists whose practice and work methods I have the deepest respect for, such as Alexander Tovborg, Magnus Andersen, Ida Ekblad, and Mads Westrup, who, in contrast to me, have a far more traditional approach to painting, which fascinates me and inspires me on a different level. Of course I look at artists who work with other medias than painting, for instance Isa Genzken, Lone Haugaard Madsen, Klara Liden and Simon Starling. One of the pieces that I was most moved by this year was a video installation by Douglas Gordon named ‘k.364’, that I saw in Düsseldorf during my residency.

Often, your works refer back to the medium itself or the process of creating the work. Can you elaborate on the level of self-referentiality in your works?

I often compare people and paintings. I appreciate people who are self-reflective – people who can look into themselves and dare question their own existence and in some way, I create art that reflects on its own process, on its place in art history, or its relation to a previous set of works. As mentioned earlier, I grew up with parents who are psychologists, and it has always been easy for me to talk about life on an existential level, which manifested itself in my practice in some way. To me, a great painting is made up of X amount of different factors that the artists have to take a stand on, both in terms of the process, where the artwork fit in terms of art history, and more formalistic concerns such as composition, scale, colour etcetera. Whether a work succeeds or not comes down to these choices, and in my own artistic practice, the artwork’s relation to its own process is crucial.

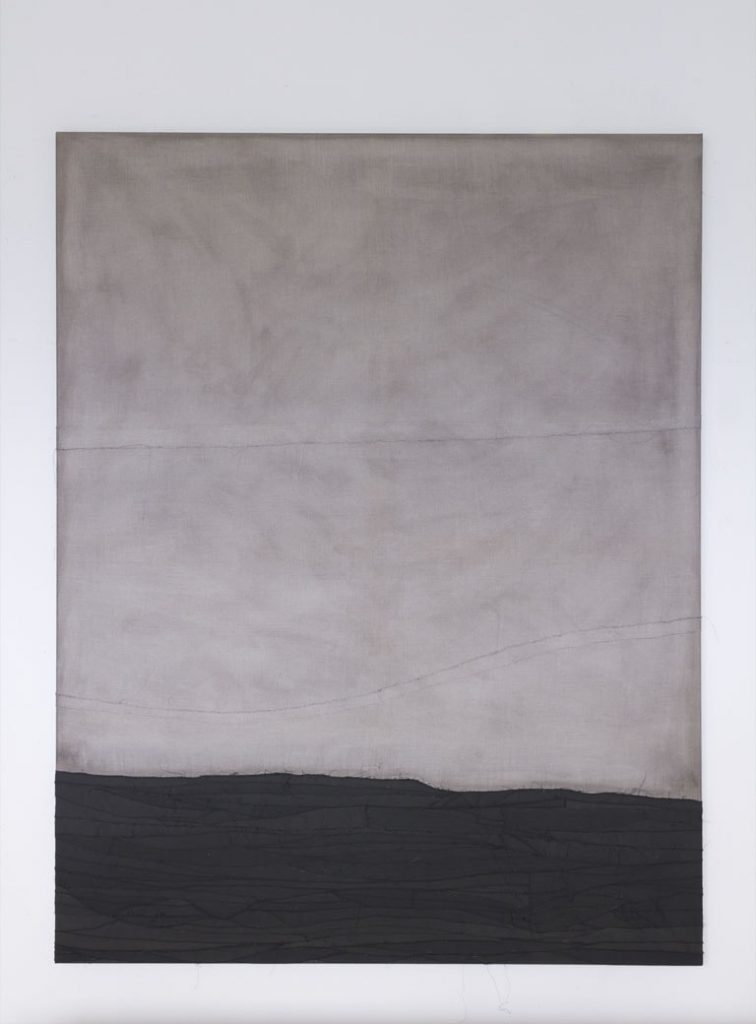

Some of your earlier works contain colour and you have gradually started to take it up again after having worked with a clear monochrome palette in recent years. Can you elaborate a bit on your use of colour and the almost dogmatic choice to not use it?

When I had my first solo exhibition at Lunch Money (today: Jacob Bjørn) in 2013, I wanted to create a solid foundation upon which I could make my decisions. Why did I choose that exact colour? Why that size? Why that title? Etcetera. In some way or another, I wanted to foreground all the decisions I made, especially in regards to colour, which only served an aesthetic function. When I began focusing more on the process and the interplay of the artworks and art history through the explicit use of references, I felt that my work stood out more clearly. When I remove the ‘adjectives’ or colours – by limiting myself to a monochrome palette – the structure of the art stands out.

But now you have started experimenting with colour again, right?

Yes, I recently started to play around with colour again and have made many new experiences with painting, which have taken a good deal of courage on my part. I associate a painting with the archetypical idea of the painter with his paintbrush, so, to me, it is a certain gesture to incorporate it into my practice, which I constantly seek to challenge. At my latest exhibition at Gether Contemporary, I tried incorporating more ‘noise’ into my works, and I thought a lot about the exhibition as ‘noisy’ or ‘messy’ – not in a negative sense, but as a form of hindrance and a way to challenge my own practice – so all the artworks had different compositions, colours, etcetera. My next exhibition with Rolando Anselmi in September 2018 stands in stark contrast to the previous one. It will revolve around the opposite principle. Here, I will paint the same painting nine times. The different techniques I use are an exciting way to draw on my earlier production and develop my own practice. It challenges me to keep questioning myself: What will happen, if I do the exact opposite of what I previously did? What happens, if I combine several techniques?

Which emotions would you like to stir in a viewer of your work? Is there a way you, as the artist behind the work, would like your work to be ideally perceived?

I do not have any particular idea of or wish for how people perceive my work. I think of it as a strength if the artworks create different reactions and perhaps even disagreement. When I think of my own experience with art, I highly appreciate the dialogue an artwork can create – a dialogue that is different depending on who you discuss it with. From my brother, who has a background in engineering, my friend in the music business, my mother, who is a psychologist, or my sister, who is interested in which emotions the artwork will stir in you – the fact that you, as an observer, can share the frame of reference with others and ‘meet’ the artwork with different viewpoints, has an enormous value. Your experience of an artwork is always a product of your history and interplay with your fellow people. I think that is interesting to observe in people’s interaction with my art.

What is driving you and what makes you come to the studio again and again?

I work in the studio almost every day. I am privileged that I am offered many opportunities to take my art in so many new directions. I agree to many events and offers and I have to create a lot of art accordingly, but above all, it is the new ideas in my head that drive me – to unfold them and see how they look in real life. It might be compared to a ‘fix’ – I get super happy, when I create an artwork that I can be proud of and that I feel succeeds.

In 2018, you attended an artist-in-residence program at CCA Andratx on Mallorca and previously you have been both in Los Angeles and Düsseldorf. What does it mean for your creative practice to be placed in a new context?

My residencies have been very different, which has a lot to do with the setting and my preceding preparations. Every place sort of create a hindrance that I have to take into account when I am creating, but all the residencies have in common the fact that I do not have all my tools with me, as I normally have. That challenges me to work in a new way. To me, a residency is a room where I can let my thoughts play freely. These places are not necessarily where I am the most productive, or where I reach some new realizations, but they are definitely a source of spiritual nourishment. I have the same experience when I teach, which recently, I have involved myself in more actively. I feel almost high when I have the chance to participate in an intellectual dialogue about an artistic practice and how it is evolving.

Since then, you have exhibited in numerous big cities around the world, including London, Berlin, New York, Paris and Rome. How do you cope with this high level of success at such an early stage in your career?

It does not play a huge part in my everyday life. Of course, I am very grateful that there are some good people who have found my art interesting and who feel that it deserves to be seen, but I have known most people I meet in my daily life for a long time and our relationships have not changed since I have gotten more artistic success. The success manifests itself most clearly in the fact that I can now live in a lovely apartment and buy art to surround myself with in my daily life, and that is definitely a reminder to me of just how lucky I am. I really do appreciate that! Then, of course, there are all the amazing experiences. I get to meet amazing people through my artistic activities, and I have grown better at meeting new people since I began traveling due to my job… and that ultimately leads to new inspiration for me.

You had your first show at a young age in November 2013 at Lunch Money, a gallery located in Aarhus, Denmark (renamed Jacob Bjørn in 2014). How did that come into place and do you remember how it felt to deal with the business of being an artist for the first time?

The gallerist Jacob Bjørn, who was planning a new exhibition, was doing research on students at both Jutland Art Academy, Funen Art Academy and the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. I was lucky that he saw potential in me and asked if I wanted to stop by the gallery and show my portfolio. I introduced him to my practice and from there we established a dialogue that led to an exhibition. I remember that my experience with him made me aware of how you speak one way with a gallerist and another way with a colleague. I met my current gallerist Rolando Anselmi when I was doing my second solo exhibition at LARM and he asked if I had learned how to ‘play the game’. At the time, I thought that I knew the dynamics of the art world pretty well, but Lars (gallery owner at LARM) told me that I still had a lot to learn, and that was true. It takes many years to learn how the ecosystem of the art world works.

What made you stay in Aarhus other than going to Copenhagen or maybe to one of the big artistic centers such as Berlin, New York or London?

I feel very privileged by all the opportunities that I have, but for now, I plan to stay in Aarhus. I like that the city is smaller and that I am not constantly distracted. It is very quiet, and that helps me in my work and helps me stay focused on my creative process. I will spend some time in the larger cities when I travel, and then I will return to my base in Aarhus, and that way of doing it suits me really well right now.

What are you focusing on at the moment?

I am working on a couple of different projects. For example, I will participate in Chart in August with Gether Contemporary. For this, I have focused on older, unfinished works that has been lying around in my studio, works that have irritated me highly. I often find irritation as a really productive element to get me started working. One of the paintings was started at the residency in West Hollywood, Los Angeles three years ago and ever since, it has been bugging me. The tension towards the painting had built up so much, that it almost felt like a boxing match. It is exciting to continue a process that started several years ago and that still has the possibility to create dialogue. Besides this, I have projects in Barcelona and Berlin, which are still taking shape. I have also just created an album cover for the Aarhus-based band Tilebreaker, which played at my opening at Gether Contemporary, and I find it really fun to move in a hybrid space, where different artistic genres melt and combine.

Has there ever been a plan B for you other than pursuing art?

No, there has never really been a plan B. I have never considered another path than art. But besides working with art, I could definitely see myself teaching a lot in the future.