Articles & Features

Artistic Collaborations: Martha Graham & Isamu Noguchi

By Tori Campbell

“I felt that I was an extension of Martha and that she was an extension of me…”

Isamu Noguchi

Introduction to the Artistic Collaboration Series

Humans have been dancing for millennia. From celebrations to mournings, and from wars to peaceful protests; as far back as known history reaches we know that humanity has been driven to dance. As societies evolved and humans collected into larger groups, dances became more formalised, and for obvious reasons artistic collaboration between musicians and dancers began to take place. In more recent decades, dancers have jumped outside of this silo of interdisciplinary collaboration, and began to work with renowned visual artists to craft innovative backdrops, props, and costumes.

By melding the works of prolific choreographers such as Lucinda Childs and Merce Cunningham with the visual languages of artistic-greats like Pablo Picasso or Donald Judd performances reached new historic heights. Such artistic collaborations between visual artists and choreographers led to some long-lasting professional relationships, or acted as a catalyst for more exploration with different partners. From one evening to entire careers, the performances created via artistic collaboration resulted in some of dance history’s most iconic performances.

“I attempted through the elimination of all non-essentials, to arrive at an essence of the stark pioneer spirit, that essence which flows out to permeate the stage. It is empty but full at the same time.

Isamu Noguchi – on Appalachian Spring

Martha Graham & Isamu Noguchi

For this edition of our “Visual Artists & Dancers: Artistic Collaboration” series we explore the work of American modern dance choreographer Martha Graham and Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi; who worked together to create unforgettable choreography and set design that sought to capture the complexity of the modern human experience.

Martha Graham

Martha Graham (1894-1991) was born in Allegheny City, presently Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to a strict Presbyterian family. By 1911 the Graham family had moved to Santa Barbara, California where Martha Graham saw a dance performance for the first time. Shortly thereafter, she began classes with the dancers she saw perform: Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn at the Denishawn School of Dancing and Related Arts, a small school that would later become acknowledged as a huge influence on Graham’s dance career.

Over a decade after beginning lessons at Denishawn, Graham left for a short period of employment at the Eastman School of Music before launching the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance on New York City’s Upper East Side. It was there that she began to coin her own technique of “contract and release” modern dance, a technique now taught at dance schools around the world. By the late 1920s Graham’s new style full of crisp aesthetics, staccato motions, and deep viscerally driven movement had gained national attention; earning her a visit to the Roosevelt’s White House — the first invitation ever extended to a dancer. Meanwhile, Japanese-American Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988) was becoming one of the nation’s most celebrated sculptors.

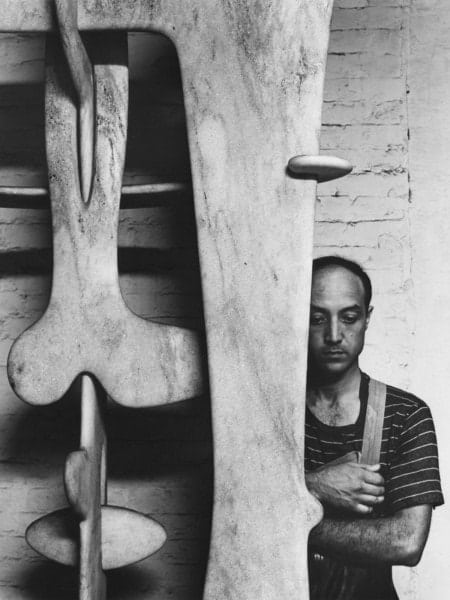

Isamu Noguchi

Born in Los Angeles to an American mother and Japanese father, Noguchi lived in Japan until his teens, when he moved to Indiana. While studying medicine at Columbia University Noguchi took sculpture classes at a small studio on the Lower East Side. He quickly decided to pursue an artistic career, and found great inspiration and a change of direction after seeing the work of Constantin Brancusi in 1926.

After securing a coveted Guggenheim Fellowship, Noguchi relocated briefly to Paris to work alongside Brancusi in his studio — shifting towards modernism and abstraction as a result of his exposure to the other artist’s work and philosophy. Noguchi was a world traveller, considered an internationalist that learned from his diverse surroundings.

Frontier

It was through his travels that Noguchi encountered Martha Graham, who commissioned him for the creation of two portraits in 1929. However, their transaction was anything but brief as Graham had found a need for more innovative set design that could complement and enhance her groundbreaking and exploratory choreography. The two began working together, and by 1935 Graham’s solo Frontier, exploring one of her favourite themes of pioneering and homesteading Americana, featured a sparse and revolutionary set crafted by Noguchi.

Appalachian Spring

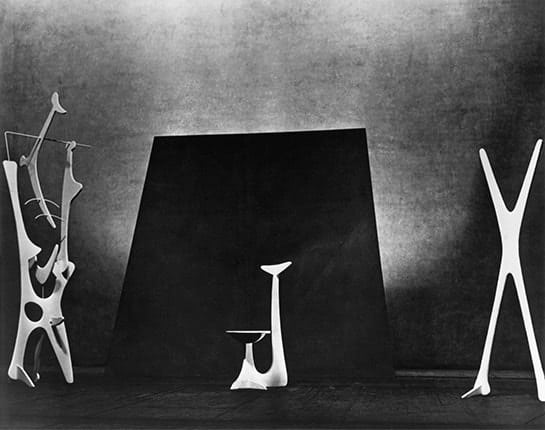

Frontier turned out to only be the beginning of Noguchi and Graham’s working relationship — which would ultimately result in artistic collaborations on over twenty works together. One of the most well-known collaborations between the two was Graham’s 1944 Appalachian Spring, famously scored by American composer Aaron Copland. The joyous piece reflects the American attitudes palpable in the end of wartime, in an uplifting performance centered around a young frontier couple on their wedding day. The set by Noguchi featured a Shaker rocking chair which he described as “a seat which is also a sculpture or a sculpture which may be sat on,” the frame of an American frontier home, and the hint of a wooden fence. The minimal set provided just enough visual information for the audience to understand the ballet’s setting, while leaving room for mystery and personal interpretation. It features prominently in a subsequent film of the ballet, which entered the United States National Film Register in 2013.

Cave of the Heart

Passionate about integrating Greek mythology and Jungian themes into her performances, Graham’s 1947 Cave of the Heart centered around the anti-heroine of Medea, the granddaughter of the Sun. For Cave of the Heart Noguchi acted as both set designer and makeshift costumer, creating a piece that stood firmly on the stage for most of the performance. However, after Medea has committed her infamous crimes she steps into the cage-like gown of spikes, donning what Noguchi dubbed a “dress of transformation” and Graham called “a chariot of flames” for her final journey to meet the Sun. In this moment Cave of the Heart became the iconic example of Graham’s ability to turn Noguchi’s sculptures into what he admired as “extensions of her own anatomy.”

Concluding the Artistic Collaboration

The two continued to collaborate on over twenty performances together, and both found great success in their independent careers. The Martha Graham Dance Company still performs to sold out audiences today, while The Noguchi Museum has proudly hosted visitors since its namesake founder and designer opened its doors in 1985.

As Janet Eilber, Artistic Director of the Martha Graham Dance Company since 2005, explained about the legacy of Isamu Noguchi and Martha Graham “They were the revolutionaries. They broke the mold . . . rejecting the decorative arts of Europe and finding an American art form that was plain-spoken and stripped down, with stark, modern ways of speaking as a dancer and as a sculptor.” Together, they defined the exploratory capabilities and essential possibilities of artistic collaboration between creative geniuses.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn more about the life and legacy of Isamu Noguchi

Enjoy the Library of Congress’ video on the iconic collaboration

Check out our new series on the lesser-known outputs of famous artists